Collective response lacking in Europe, which is divided over migrant issue

Rescuers carry a migrant out of a Spanish Coast Guard vessel at the port of Arguineguin, in the island of Gran Canaria, Spain, on Monday. Spain has received 10,361 refugee arrivals by June 18, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (PHOTO / REUTERS)

Rescuers carry a migrant out of a Spanish Coast Guard vessel at the port of Arguineguin, in the island of Gran Canaria, Spain, on Monday. Spain has received 10,361 refugee arrivals by June 18, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (PHOTO / REUTERS)

Editor's note: World Refugee Day falls on June 20 each year. As the influx of refugees pouring into Europe has taken a heavy toll on the continent, this page takes a close look at the current refugee crisis in Europe as well as the efforts that help refugees to not only survive but also thrive.

As the full horror of the latest migrant boat sinking in the Mediterranean becomes ever clearer, with at least 81 people dead and hundreds missing, the timing of Tuesday's World Refugee Day, devoted to honoring the plight of people forced from their homes by conflict and persecution, could hardly be more grimly apt.

The vessel sank in international waters off the coast of southwestern Greece, and with many unconfirmed reports about its capacity circulating, the full toll may never be known.

Once again, the problems of the world are washing up on Europe's shores, and the range of reactions has included shock, outrage, and political anger.

Mass population movements within Europe are nothing new. London's Imperial War Museum estimates 65 million people were forced from their homes during World War II, and the United Nations' Refugee Agency says as many as 4 million people became refugees as a result of the war in former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

The human fallout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict is continuing, but it is the external nature of this mass movement that is different.

Years after the Syrian civil war began, its shockwaves are still felt way beyond its borders. Adding to this, a UN report in March said 100,000 new refugees from Somalia had arrived in Ethiopia in the previous month, and recent figures identified the Sudan civil war as a major contributor to a record 110 million people being displaced worldwide by the end of last year. It is clear this is an issue unlike anything Europe has seen before — and different countries are reacting in different ways.

Even before the latest tragedy, figures from the International Organization for Migration showed that between January and March, at least 441 people drowned while crossing the Mediterranean, making it the deadliest three-month period since 2017.

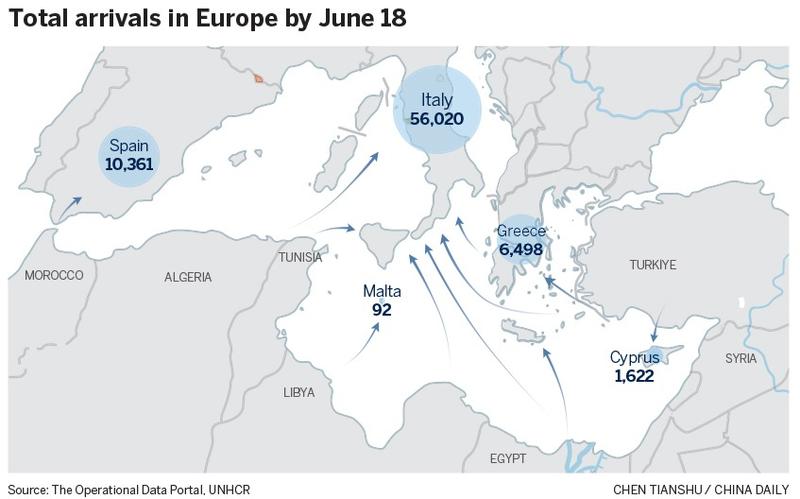

Total arrivals in Europe by June 18 are 74,593, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, with 72,951 sea arrivals. Up to that same date, the estimated number of dead and missing is 1,159.

Schoolgirls line up at the Saranan refugee camp in Pishin district, Balochistan Province, Pakistan, on Monday. (PHOTO / AFP)

Schoolgirls line up at the Saranan refugee camp in Pishin district, Balochistan Province, Pakistan, on Monday. (PHOTO / AFP)

The two countries on the geographic front line of dealing with the huge numbers trying to enter Europe are Italy and Greece. Both have had elections in the past 12 months, and perhaps not coincidentally, both saw right-wingers triumph — Kyriakos Mitsotakis and his conservative New Democracy party in Greece, and in Italy, Giorgia Meloni, of the Brothers of Italy party, who became the country's first female prime minister, and its most right-wing leader in many years.

Barbara Serra, an Italian and British journalist, said immigration had been a factor in Meloni's rise to power, but now she faces the challenge of how to deal with it.

"It's one thing to complain about a system that doesn't work when you're in opposition, but it's another thing altogether when you're in government, so she has to resolve it," she said. "You can't shrug it off, the challenge for her is that she now has to make it work."

For many refugees, it is Europe that is the desired destination, rather than Italy or Greece, which just happen to be the nearest access points, Serra said, adding that the absence so far of a coordinated European response is a major problem.

"The issue has been going on for a long time, but at the heart of it, it comes down to geography. The coastlines of Greece and Italy are the coastline of Europe.

"Meloni will say that there's been a big split between the countries of northern and southern Europe over the issue, and the European Union has left us to our own devices so we need to protect our own borders because these people are coming to Europe, not to Italy, but many of them end up staying here.

"It's fair to say migration has been used as a political football. She has exploited it, but there is an issue that is still unresolved. It's much more complicated than just saying 'immigration is bad'. What helped her into power more than migration was COVID, as she was the only real opposition when that was going on."

Pablo Swedberg Gonzalez, professor at the IE School of Economics, Politics and Global Affairs in Madrid, agreed that a European problem requires a European solution.

"Migration flows affect all EU countries to varying degrees and therefore require a collective response," he said. "Acting separately may push migrants into more dangerous routes and circumstances, including smugglers, who are associated with serious human rights violations and deaths.

"The EU has not been able to advance more rapidly due to the diversity of interest and priorities among member states. Additionally, migration has been heavily politicized and every party in power serves a different constituency, so has its own agenda."

The initial agreements that laid the foundation for the EU were based on binding neighbors together so that they could never go to war again, or witness endless lines of wandering refugees, as seen after World War II.

But while this has not been repeated internally, the current challenges of the incoming refugee crisis have exposed deep differences among member states, not only of economic ability to absorb the costs, but also of attitudes toward outsiders and integration.

Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban has long gone against the flow of immigration, and remains staunchly opposed to wider European initiatives to share the load.

His country's population is in long-term decline, but with less than 2 percent of its population born outside Hungary, he has no interest in bolstering those numbers with outsiders.

"Economic immigration … only brings trouble and threats to European people," he told state television in 2015. "Therefore, immigration must be stopped. That's the Hungarian stance. Hungary will not become a target destination for immigrants. We will not allow it, at least as long as I am prime minister and as long as this government is in power."

His fourth electoral success in April suggests many Hungarians agree.

Coordinated policy

Earlier this month, the European Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson secured majority support for a proposal to build a coordinated migration policy among EU member states. The only objectors were Poland and Hungary.

Poland has accepted 1.6 million Ukrainians, the UNHCR said, but when it comes to other countries, its attitude is very different.

"Forced relocation does not solve the problem of migration, but it violates the sovereignty of the member states," Poland's Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki tweeted.

Orban's spokesperson referred to imposed relocation — something not foreseen in the proposal — and said, "This is unacceptable, they want to forcefully turn Hungary into a migrant country."

Spain's far-right Vox party has also weaponized immigration in recent local elections, with its vice-president Jorge Buxade speaking of "the policy of open borders, imposed by the elites, (which) has imported violence and insecurity, destroying the identity of our neighborhoods and demonstrating that multicultural societies are multi-conflictive", and people being "forced to coexist in their neighborhoods with cultures that are incompatible with Western cultures".

Although what became World Refugee Day was established in 1951, up until December 2000, it was known as Africa Refugee Day.

Twenty years later, a quick look at headlines around the world will confirm that its global renaming remains as correct and as depressingly relevant as ever.