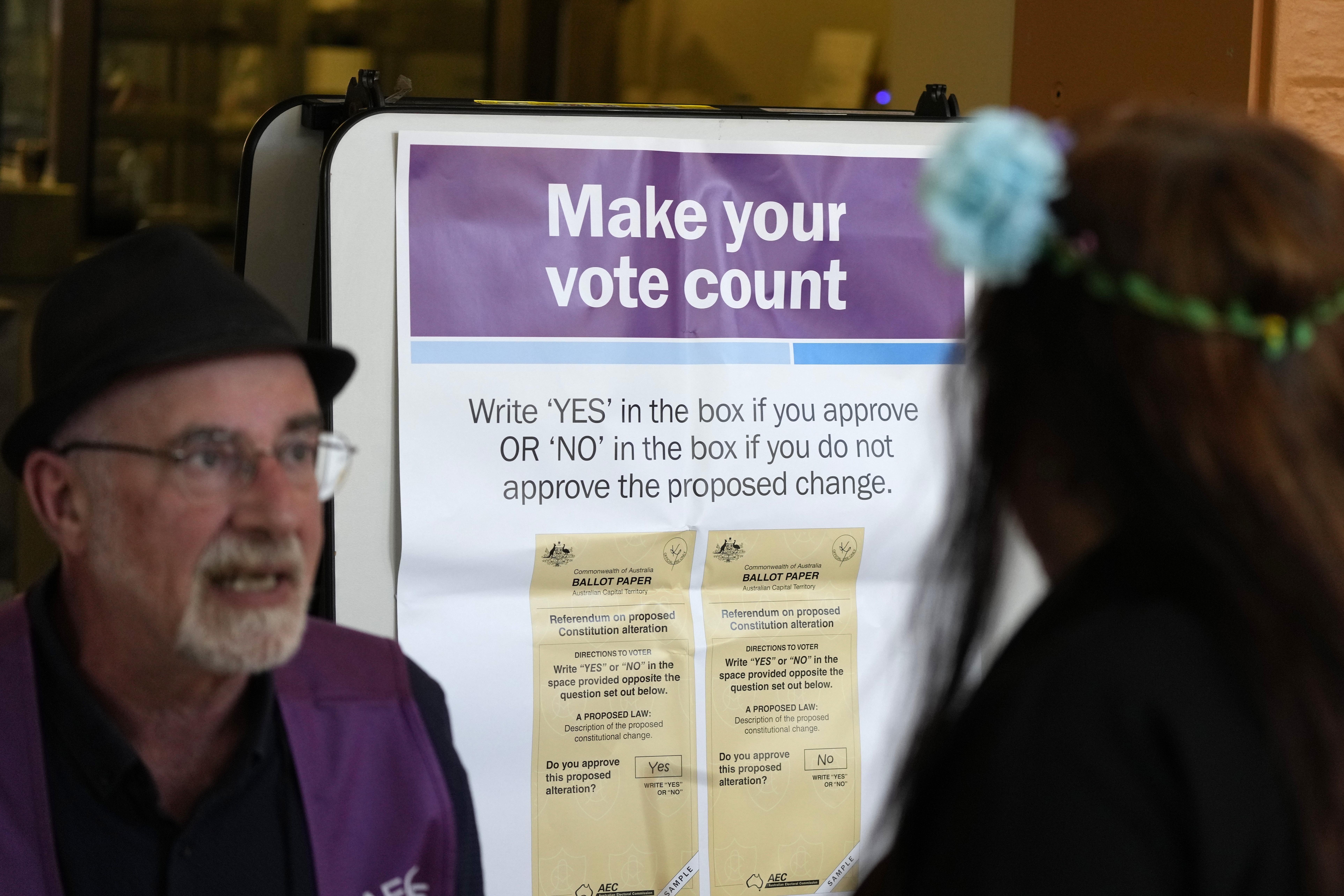

A polling place volunteer (left) assists a woman at a polling place in Redfern as Australians cast their final votes in Sydney, Oct 14, 2023, in their first referendum in a generation that aims to tackle Indigenous disadvantage by enshrining in the constitution a new advocacy committee. (PHOTO/AP)

A polling place volunteer (left) assists a woman at a polling place in Redfern as Australians cast their final votes in Sydney, Oct 14, 2023, in their first referendum in a generation that aims to tackle Indigenous disadvantage by enshrining in the constitution a new advocacy committee. (PHOTO/AP)

The referendum rejection of recognizing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the constitution by giving them a voice in the Federal Parliament on Oct 14 was a defining moment for Australia, not just for its indigenous people but for the country.

Many of the indigenous leaders who had led the “yes” and “no” campaigns said they would remain silent for the next week to engage in quiet reflection.

Australia’s indigenous population makes up less than four percent of the country's 26 million people but they have a history and attachment to the land going back 65,000 years.

But in the 200 years of European settlement, Australia’s indigenous people had been marginalized and left behind while those around them prospered. Only now is the country waking up to the harsh reality of Australia’s brutal past and its treatment of its indigenous people.

In many ways, the proposed “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to the Federal Parliament” would have gone some way in giving Australia’s First Nations people a say in those matters that affect them, such as education, health, housing and justice.

ALSO READ: Australia rejects Indigenous referendum

The Voice was to have been an independent and permanent advisory body to the government of the day. There was nothing sinister in Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s election pledge to see the Voice through to its logical conclusion.

What started out as a reasonable proposal by Albanese and his government instead became a divisive political issue fueled by hate, fear, and racism.

The “no” campaign impacted on indigenous communities although the vast majority of First Nations people voted “yes”.

All six Australian states and one territory voted “no” for the Voice; only the Australian Capital Territory voted “yes”.

Volunteers talks with people coming to vote at a polling place in Redfern as Australians cast their final votes in Sydney, Oct 14, 2023, in their first referendum in a generation that aims to tackle Indigenous disadvantage by enshrining in the constitution a new advocacy committee. (PHOTO/AP)

Volunteers talks with people coming to vote at a polling place in Redfern as Australians cast their final votes in Sydney, Oct 14, 2023, in their first referendum in a generation that aims to tackle Indigenous disadvantage by enshrining in the constitution a new advocacy committee. (PHOTO/AP)

Allan Patience, from the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne, said, “The Voice cannot go anywhere.”

The one glimmer of hope is that voters in the 18-34 age range appear to have voted nearly 80 percent in favor of the Voice, said Allan Patience from the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne

“In the form it was presented at the referendum, it is finished. In my view, that is very sad,” he told the China Daily.

He said the Voice failed for several reasons, such as the decision by the Opposition in the Parliament to oppose it.

“No referendum in Australia has ever passed without bipartisan support from the major political parties,” he said.

“Secondly, social media unleashed a remarkable number of distortions of what the proposal was all about, many outright lies.”

“Thirdly, the campaign unleashed some disturbingly extremist views of racists, neo-Nazis, and a range of quite crazy people.”

Some claimed, for example, that if the proposal was passed, “white Australians would not be allowed to swim at public beaches, that they would lose their homes and properties, that it was a ruse by the United Nations to take over Australia”, he noted.

“In short, the Voice was the victim of the kind of Trumpian politics and populist extremism we see coming out of the USA today,” Patience said.

ALSO READ: Aussie PM takes share of blame for referendum failure

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese shows his support for a yes vote during a visit to Adelaide, Oct 13, 2023. (PHOTO/AP)

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese shows his support for a yes vote during a visit to Adelaide, Oct 13, 2023. (PHOTO/AP)

The Guardian newspaper’s indigenous affairs editor Lorena Allam in an opinion piece Oct 14 said, “Plenty will be said in the coming days about the campaign and how it all went down, much of it by non-indigenous people who already have power, influence and access to the media to prosecute their arguments. In that way, the country will be much the same as it was last week: a place where the voices of First Nations people are drowned out, talked over and misrepresented in a national conversation that is forever about us, without us.”

Patience said that for the time being, “there is no proposal on either side of mainstream politics to offer an alternative policy to the Voice”.

“Indigenous Australians are left in a limbo as the statistical gap between them and white Australians is yawning ever wider,” he said.

“The one glimmer of hope is that voters in the 18-34 age range appear to have voted nearly 80 percent in favor of the Voice. At the same time, a significant majority of voters in the seats of Independent MPs (the so-called Teals) also voted in favor. This suggests that a coming generation of political leaders is likely to be more progressive than the present lot.”

ALSO READ: Indigenous Australians vow silence after referendum fails

Sana Nakata, principal research fellow, James Cook University wrote on The Conversation website on Oct 14: “The political subjugation and further marginalization of First Nations peoples is no longer historical legacy but a contemporary decision reinscribing centuries of paternalism: that we are not peoples deserving of a protected right to be heard on matters that affect us.

“We asked for change. We asked to be heard. We asked the Australian people to walk with us,” Nakata said.

“And so now we are where we have always been, left to build our better futures on our own.”