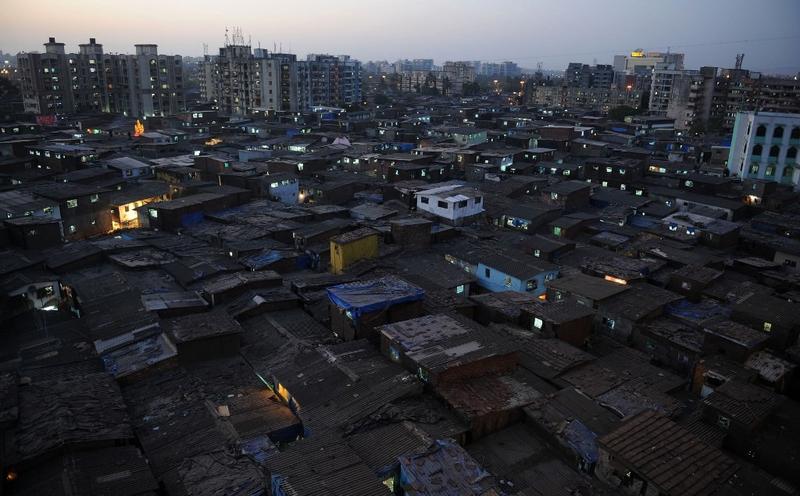

In this April 19, 2010 photo, Dusk descends over Dharavi, Asia's biggest slum, in Mumbai. (PUNIT PARANJPE / AFP)

In this April 19, 2010 photo, Dusk descends over Dharavi, Asia's biggest slum, in Mumbai. (PUNIT PARANJPE / AFP)

When government official Kiran Dighavkar heard that a 56-year-old man who’d recently died in the Mumbai suburb of Dharavi had tested positive for Covid-19, he knew his next moves would determine the trajectory of the outbreak in India’s commercial capital.

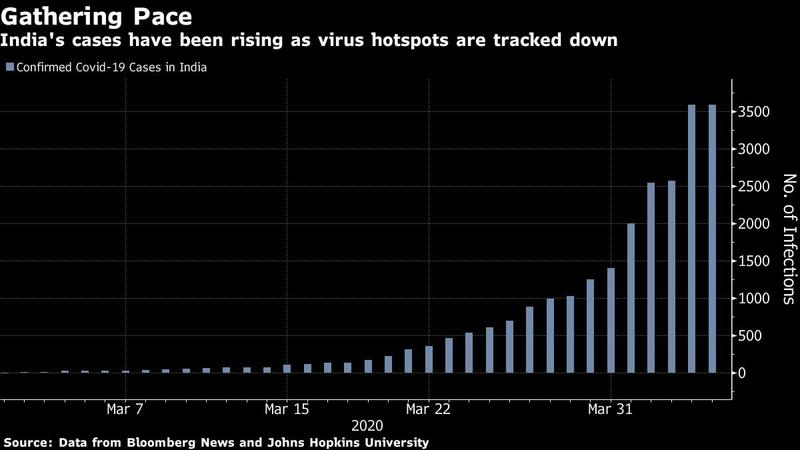

Mumbai is turning into somewhat of an epicenter for the outbreak in the country, having reported more than a tenth of India’s 3,374 cases and almost half of its deaths, according to official data reported Sunday

The man, who died on April 1, lived with seven members of his family in a 400 square foot flat adjoining Asia’s most densely packed slum, where as many as 80 people share a public toilet. Not only could infection spread rampantly, but home quarantine for those testing positive would not be an option.

ALSO READ: Oldest Asian railway turns coaches into India isolation wards

Officials had an added problem. Fearing stigmatization, the man’s family were not fully co-operating with authorities.

Dighavkar, an assistant commissioner for the city’s municipality, and his team in charge of the area surrounding Dharavi, turned to mobile phone providers to retrace the man’s movements. His contacts were tested and high-risk ones, those with respiratory or other conditions, were isolated. Authorities’ efforts are focused on preventing the pathogen from racing undetected through the slum where a population the size of San Francisco packs into an area smaller than New York’s Central Park.

Trying to trace and contain outbreaks in settlements such as Dharavi -- 5 kilometers from Mumbai’s key business district and home to India’s biggest stock exchange and the local headquarters of JPMorgan Chase & Co -- are critical in India’s fight against the deadly coronavirus, which has sickened over 1.2 million people globally and killed more than 64,000.

With a population of about 1 million, many of whom are migrant laborers from villages thousands of miles away, keeping the contagion from spreading in Dharavi could help prevent hospitals in Mumbai and across India from being overwhelmed.

Mumbai is turning into somewhat of an epicenter for the outbreak in the country, having reported more than a tenth of India’s 3,374 cases and almost half of its deaths, according to official data reported Sunday. This could be partly because of higher levels of testing but also due to a high proportion of low-wage migrant population as well as globe-trotting corporate executives.

In Dharavi, which sleeps thousands of daily wagers and hosts businesses run from huts with a tarpaulin roof -- at times without government permissions -- tensions and mistrust are rising. Some youth pelted stones after police tried to seal the area and keep residents from stepping out of their homes.

Vegetable vendors wear protective masks while waiting for customers at a market during a lockdown imposed due to the coronavirus in Mumbai, India, April 5, 2020. (PHOTO VIA BLOOMBERG)

Vegetable vendors wear protective masks while waiting for customers at a market during a lockdown imposed due to the coronavirus in Mumbai, India, April 5, 2020. (PHOTO VIA BLOOMBERG)

We are talking about a slum where 10-12 people live in 10x10 feet tin hutments. You can’t expect them to sit at home all day long. They pay 25 rupees for a gallon of water, you’ll tell them to wash their hands frequently. Eighty people share a public toilet, you’ll tell them to not leave their house. How is that possible?

Vinod Shetty, director at the non-profit Acorn Foundation

“We are talking about a slum where 10-12 people live in 10x10 feet tin hutments. You can’t expect them to sit at home all day long,” said Vinod Shetty, director at the non-profit Acorn Foundation, which works with sanitation workers in Dharavi. “They pay 25 rupees for a gallon of water, you’ll tell them to wash their hands frequently. Eighty people share a public toilet, you’ll tell them to not leave their house. How is that possible?”

Shetty and authorities Bloomberg News interviewed say the residents of Dharavi are aware of the risks of Covid-19. But they’re also scared, just like millions of poor people across the globe, of losing their jobs, of being unable to provide for their families, and of being hauled away by police. It’s crucial that the government use community leaders in these slums to build trust, Shetty says.

“In Dharavi, it’s very difficult to get the facts right. A lot of times residents are not telling us the truth about their travel history or where they have been out of fear,” said Dighavkar. “They fear they will be nabbed and punished for not following lockdown rules.”

Local authorities have quarantined about 3,000 people in Dharavi -- or 0.03 percent of its population -- three others have been infected and results of as many as 25 are awaited. The dead man’s family has tested negative. Authorities say they are providing food and water to affected residents.

A sports club in the vicinity is being converted into a 300-bed isolation facility and Mumbai’s municipality invoked a century-old law, created to curb the 1897 bubonic plague, to take over a 50-bed hospital that will house asymptomatic cases. The hospital will be paid 3 million rupees each month, according to a report in the Mumbai Mirror newspaper.

While six teams of doctors and nurses and 170 health workers are dedicated to Dharavi alone, they can’t mitigate the economic pain of India’s three-week lockdown, the world’s largest isolation effort that may tip the nation’s economy into its first contraction in more than two decades.

Pedestrians walk along near-empty roads during a lockdown imposed due to the coronavirus in Mumbai, India, March 25, 2020. (PHOTO VIA BLOOMBERG)

Pedestrians walk along near-empty roads during a lockdown imposed due to the coronavirus in Mumbai, India, March 25, 2020. (PHOTO VIA BLOOMBERG)

Stranded workers

Sheikh Mobinuddin, who runs a garments and recycled plastics business in Dharavi, blames the suddenness of the lockdown for paralyzing residents. Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the decision in an 8 pm televised address March 24 and it took force at midnight.

About 100,000 poor migrants employed in Dharavi’s leather and garment-making units are being fed by the community or by political parties as businesses are shut, Mobinuddin said. He predicts they will rush to their homes in other states once public transport resumes, and risk carrying the virus deeper into the rural hinterland where health facilities are sparse.

Since the initial death in Dharavi, a 35-year-old doctor has also tested positive (authorities say he probably contracted the virus from his patients in a private hospital nearby) as well as a 30-year-old woman with fever and cough. Both live in buildings adjoining the slum. A 48-year-old from the hutments has been hospitalized with Covid-19 as has a sweeper who works in Dharavi but stays elsewhere.

READ MORE: Indian farmers face shortage of harvest labor amid lockdown

Residents are worried about what would happen if the virus takes root in the shanties, said Raju Korde, who owns a garments shop in Dharavi.

“Only God can save people then,” the 50-year-old said. “We’ll have to trust our own immunity. That’s the only option.”