Educators in rural areas go the distance during the pandemic

(LI MIN / CHINA DAILY)

(LI MIN / CHINA DAILY)

Shu Hang, a mathematics teacher at a village primary school in Xiangyang, Hubei province, has remained on the school’s grounds since the end of January.

During holidays, a small group of teachers take turns as campus caretakers.

Shu, 32, who teaches second-grade students at Erwang Primary School, drove to the school on Jan 28 as he was scheduled to take care of the campus during Spring Festival.

He decided to remain on campus after roads were closed due to COVID-19, making it difficult for colleagues to reach the school located in Juwan in the countryside.

A lockdown was enforced in Xiangyang on Jan 27.

During the outbreak, Shu worked as a cleaner, spraying disinfectant in classrooms, dormitories and toilets. As a gardener, he pulled weeds and trimmed trees, and as a guard stood watch from a small gatehouse in uniform.

On Feb 10, Shu and 17 colleagues began giving lectures online for the first time in their careers.

Shu gives three math lessons every afternoon, while a colleague gives three lessons in Chinese-language studies every morning.

The school has 18 teachers and 172 students from four nearby villages.

The school, set among golden rapeseed flowers and verdant crops, is far from locals’ homes and is connected by road to the nearest village a kilometer away.

Shu has been home only twice — in January and early February — to collect fresh clothing. He has taught at the school since the fall semester in 2017, after transferring from another elementary school in Juwan.

He became a village teacher in Juwan in 2013, after graduating from college and serving two years in the army.

“As a young single man, there is not much to do at home under the lockdown, so I would rather stay here and work. I don’t feel scared or lonely — I have a full day’s work and time flies,” he said.

Every few days, Shu videoconferences with parents in the nearby county seat. The headmaster often visits the school and leaves food at the gate. Sometimes, the pair talk on either side of the gate, observing social distancing.

Shu and other teachers at rural schools spend a great deal of time adapting to online education, which is especially challenging for older members of staff.

Cheng Kaixiu, 55, head teacher at Juwan Central Primary School in Xiangyang, has learned to teach using video apps. She finds it hard spending several hours daily staring at a small screen when teaching and correcting students’ homework, which is submitted online.

She wears reading glasses, but light from her cellphone makes her eyes water. To cope, she projects images from her phone onto the wall with an LED lamp.

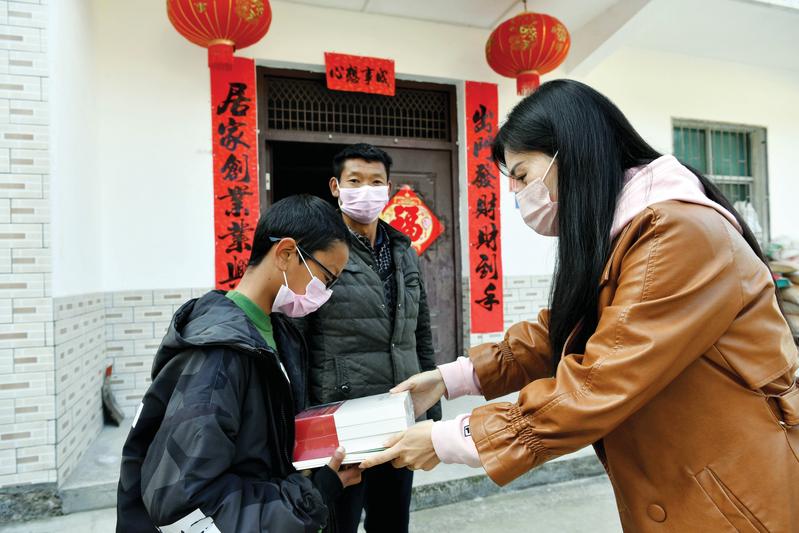

Government officials in Xiangyang visit households to deliver donated cellphones and study material to students from poverty-stricken families. (YANG TAO / FOR CHINA DAILY)

Government officials in Xiangyang visit households to deliver donated cellphones and study material to students from poverty-stricken families. (YANG TAO / FOR CHINA DAILY)

Shu has downloaded teaching videos to make his lessons more lifelike and help students understand the outbreak. But one or two students always miss his class during online sessions. In recent years, the central government and local authorities have placed increased emphasis on improving basic education in rural areas. They have invested significant amounts to enhance infrastructure and the quality of teachers.

At Shu’s school, a new three-story dormitory accommodates students who live far from campus. PowerPoint presentations are commonly used in classes, and more than half the teachers are relatively young.

However, with the nation turning to online education during the outbreak, the plight of rural pupils has worsened.

Although 854 million Chinese were using the internet by June last year, as of 2018, only 38.4 percent of rural areas could access cyberspace, far lower than the national average, according to the 43rd China Statistical Report on Internet Development released last year.

Education in remote areas saw smartphones suddenly become daily necessities. Some rural pupils who do not have a phone or internet access have missed virtual classes.

Chang Yan, who teaches ninth-graders at Juwan Second Junior High School in Xiangyang, said a poverty-stricken student of hers had cried during a phone call to her, afraid of missing an online class.

There is just one phone at the student’s home, with no internet access. The phone’s small memory usually makes it jam when surfing the internet. Without a connection, the girl was also unable to attend classes.

Some of Shu’s students have missed online sessions because they share one phone among siblings, and when lessons overlap, someone has to give way.

Some rural families cannot afford home broadband, or to buy extra phones — or even one — for their children. Parents are also worried that frequent access to mobile devices could lead to video game addiction or harm their children’s eyesight.

Education authorities and rural teachers are trying to bridge the divide.

In Juwan, schools have collected the cellphone numbers of students from poorer families and supplied them to telecom companies, which provide 20 free gigabytes of monthly digital service for online education.

At night, Shu calls students who have missed online classes to give them details of lessons. Chang said she paid for a cable television subscription for the student who cried, enabling her to watch state-approved lessons.

Rural teachers are examining every possible way to help vulnerable students.

With shops closed due to the outbreak, Zhang Xiaohong, a teacher at Mingde Primary School in Xiangyang, received a request from one mother to help buy a smartphone for her child. Zhang asked a friend, who owns a phone store, for assistance. Because roads were closed, Zhang walked to the family’s home to deliver the phone.

At two middle schools in Juwan, ninth-grade teachers packed textbooks and other materials students had not taken home for the winter vacation, and had these delivered. Online classes have had limited impact when students do not have their textbooks at home.

Shu Hang, who has remained alone at the school in Xiangyang since the end of January, works at the entry gate. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Shu Hang, who has remained alone at the school in Xiangyang since the end of January, works at the entry gate. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Party secretaries have helped teachers with deliveries along with obtaining necessities for villagers. Xiangyang made it a rule that textbooks had to be delivered to students by March 18.

Ninth-grade educators such as Chang are under greater pressure.

Along with the gaokao (national college entrance examination), the zhongkao (senior high school entrance exam) offers rural students a chance to shake off poverty and change their future. The zhongkao is usually held in Hubei in June.

Chang was anxious about one of her students taking this exam. “I’m afraid that I will fail to meet my responsibilities.”

Visiting the boy’s home last year, she found there was only one cellphone in the house, which could not connect to the internet. The student felt too embarrassed to ask for help. She contacted the village council through the town government for help. The student finally attended online classes at a village official’s home.

Ma Quanmin, from Juwan First Junior High School, said: “The delay in starting the new school term caused by the COVID-19 outbreak has significantly increased the psychological pressure on ninth-grade students.”

The virus has disrupted learning, affecting in particular children whose parents have left rural areas for work in large cities, those from single-parent homes and those with disabilities.

It took more than 10 phone calls from teachers to persuade one student to take online classes.

Li Liangying, a colleague of Ma’s and head ninth-grade teacher, has a girl from a poverty-stricken family in her class. The girl’s father had died and her mother has mental illness. The student failed to submit homework and repeatedly withdrew from online study groups. She finally returned to class after several calls from Li boosted her confidence.

Most migrant workers who returned to their families to celebrate Spring Festival became stranded in their hometowns during the pandemic.

Ma Shuangwei, head of Fanwan Primary School in Juwan, said: “As students have not been at school, I am worried whether parents are supervising their children’s studies at home.”

Rural parents are at a disadvantage when it comes to finances, ability and time to guide their children in remote learning.

Two young parents in Juwan quarreled with each other, both unwilling to lend their child their mobile phone for online classes, as they were playing with the device.

Liu Changbin, head of the town’s education authority, said, “It’s difficult for many to imagine that such a thing can happen nowadays, but it’s a true grassroots story.”

When classes resume, Juwan intends to use weekends to help pupils catch up. Given the disparity between rural and urban areas, students from the countryside may not perform as well if they cannot attend physical classes.

“This gap certainly exists,” Liu said. “The point is not to make it too huge.”

Online education has meant that Shu has had to slow the pace of his lessons to give students time for review.

He hopes the outbreak will end soon, fearing his 27 pupils are falling behind due to the disruption. Last semester, his class ranked second in the town for math, and he is eyeing first place.

“They have a strong desire for knowledge,” Shu said.