Voters fill in their ballot papers at booths at the Poi Ching School polling station in Singapore, July 10, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Voters fill in their ballot papers at booths at the Poi Ching School polling station in Singapore, July 10, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Most political parties around the world would be thrilled to win 89 percent of seats in an election. Not in Singapore.

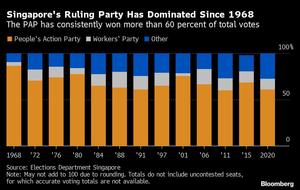

The worst showing for the ruling People’s Action Party, or PAP, since independence in 1965 prompted analysts to declare a “vote for change” that will trigger “soul searching” among the country’s leaders. Supporters for the main opposition Workers’ Party – which took 10 of 93 seats up for grabs – waved flags, blew whistles and beat drums like they were about to take office.

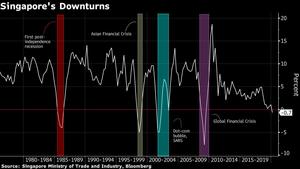

Much of that reaction reflects just how tightly the PAP has clenched the levers of power over the decades. It’s a very high bar for it to continue winning so many seats in every election even with an electoral system that has built-in advantages for the ruling party, and this vote was held when a global pandemic helped trigger the city-state’s worst-ever economic slump.

Look at this population – the youngsters – they are prepared to vote against the government in times of a crisis, which is very unprecedented.

Bilveer Singh, Associate Professor, National University of Singapore

Potentially more concerning for Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, however, was that the result upended the conventional wisdom that traditionally risk-averse Singaporeans would strongly back the PAP in an emergency. That alone could have a big impact on policy, raising questions about how leaders positioned to succeed Lee handled the virus and why more young voters are said to have embraced opposition calls for both a stronger social safety net and a more open democracy.

“Look at this population – the youngsters – they are prepared to vote against the government in times of a crisis, which is very unprecedented,” said Bilveer Singh, associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s department of political science. “It has never happened.”

READ MORE: S'pore ruling PAP cedes ground to opposition in pandemic poll

In the early hours of Saturday, Lee said the PAP had won a “clear mandate” even though its 61.2 percent share of the popular vote – slightly more than its all-time low in 2011 – was less than he had hoped. He vowed to take Singapore “safely through the crisis and beyond” before handing over power to the so-called fourth generation of leaders.

“The results show also a clear desire for a diversity of voices in Parliament,” Lee said, while adding that the outcome reflected the “pain and uncertainty” caused by a loss of income, anxiety over jobs and virus-related disruptions.

Lee hinted at some changes ahead, saying government policies must reflect the younger generation’s “significantly different life aspirations and priorities” compared with older Singaporeans. Still, he implored the youth to heed lessons “hard won by their parents and grandparents so that they don’t have to learn them all over again and pay a high price.”

As one of the most trade-reliant economies in the world, Singapore has taken a severe knock during the pandemic. Officials are predicting that gross domestic product will contract as much as 7 percent this year. Data on Tuesday will probably show the economy already entered a recession in the second quarter.

“There may be a greater need to think out of the box for economic strategies in a post-COVID world,” said Selena Ling, head of treasury research and strategy at Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp, citing debates over fiscal sustainability and accountability, minimum wages, foreign worker policy and reliance on multinational corporations.

The Workers’ Party had campaigned on a slew of policies aimed at helping lower-income Singaporeans, including unemployment insurance, a minimum wage and incentives to hire locals over foreigners.

Party chief Pritam Singh, who will become Singapore’s first official opposition leader, said he was humbled by the gains even though “it’s still not exactly a quantum leap.”

“I’m not feeling euphoric at all,” Singh told reporters. “In fact I think there’s a lot of work to do.”

ALSO READ: Explainer: Why one party dominates Singapore politics

The election results will likely spur the government to enact measures to strengthen the social safety net and recalibrate its foreign worker policy even while it stresses to the business community that it’s not turning insular, according to Leonard Lim, Singapore country director for regional consultancy firm Vriens & Partners. The government had already tightened restrictions on foreign labor in industries such as retail while allowing imported talent for higher-skilled roles.

“Plenty of opposition candidates have rammed home the point that the PAP’s long-standing openness to foreign labor means less good quality jobs for citizens,” Lim said. “It’s low-hanging fruit and a very strategic tactic, especially when many citizens, especially middle-class white-collar workers, are losing sleep about job issues amid Covid-19.”

On the campaign trail, Prime Minister Lee had emphasized the government’s moves to stabilize the economy and limit job losses through massive wage subsidies, pledges to create 100,000 fresh work and training opportunities, and re-skilling workers toward next-generation industries. His government allocated S$93 billion (US$67 billion) in special budget support to cushion the economic blow, and dipped into its reserves for only the second time to finance the spending.

In addition, the government is investing for research and development in areas such as artificial intelligence and biomedical sciences, supplementing ongoing digitization efforts that include building Singapore into a fintech hub and getting the island’s food stalls and wet markets to adopt e-payments.

Still, Lee has repeatedly said Singapore needs to attract investments from multinationals to generate sustainable economic growth over the long haul. He blasted opposition proposals for a minimum wage and universal basic income as “fashionable peacetime slogans, not serious wartime plans.”

For Lee, who has run Singapore since 2004, the election was personal. He has signaled he intends to step down by the time he turns 70 in 2022, with Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat set to take over.

Yet the election saw the prime minister being attacked by his own brother, Lee Hsien Yang, who criticized the government’s handling of the pandemic and the capabilities of the next generation of the PAP’s leaders. Singapore has been one of the hardest hit places in Asia, with cases topping 45,000 -- mostly migrant workers residing in dormitories -- even though the fatality rate remains low.

Lee Hsien Yang also called for an overhaul of the political system, a view shared by the Workers’ Party. It has sought a range of political reforms, such as abolishing the group-representative constituency system that it says has helped the PAP maintain its lock on Parliament. It advocates single-member constituencies, an independent Elections Department and court reviews of government directives under a so-called fake news law passed last year.

The extent to which the PAP will change hinges on internal discussions and some form of leadership transition that will happen before Singaporeans are scheduled to vote again in 2025, according to Bridget Welsh, an honorary research associate at the Asia Research Institute of University of Nottingham Malaysia.

“If anything,” she said, “the pandemic has taught Singapore that the PAP needs to listen to alternative voices.”