Park Yang-woo, South Korea's culture, sports and tourism minister, poses for a photograph following an interview in Seoul, South Korea, on July 23, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Park Yang-woo, South Korea's culture, sports and tourism minister, poses for a photograph following an interview in Seoul, South Korea, on July 23, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

South Korea warned that Japan risked reigniting tensions if it didn’t acknowledge past forced labor abuses, saying Seoul was prepared to build a regional coalition to hold Tokyo to account for its colonial behavior.

South Korean Culture Minister Park Yang-woo said in an interview Thursday that international criticism would be “unavoidable” without public recognition by Japan that human rights abuses occurred at the Hashima industrial site off the coast of Nagasaki. While Park declined to elaborate on the countries South Korea would lobby for support, China has long been among the most vocal critics of Japanese efforts to explain its wartime past.

If Japan keeps distorting the history, Korea will respond with other Asian countries with other issues, as well

Park Yang-woo, South Korean culture minister

“If Japan keeps distorting the history, Korea will respond with other Asian countries with other issues, as well,” Park told Bloomberg News in Seoul. “We will also rightfully support those countries that face circumstances similar to what we are facing right now.”

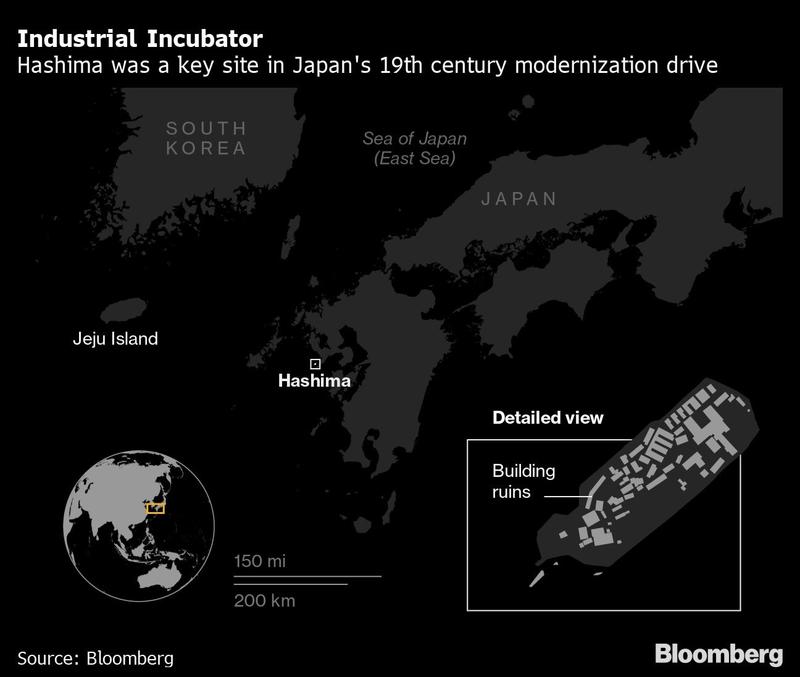

The decades-old forced-labor dispute has reemerged since Japan opened an information center in Tokyo last month that included materials suggesting conscripted workers at Hashima were paid and well-treated. South Korea considers the display a breach of its 2015 agreement to support Japan’s ultimately successful bid to get the 19th century industrial incubator listed as an Unesco World Heritage Site. They want Tokyo to change the exhibit or have the heritage status rescinded.

The disagreement could undermine a truce that ended an unprecedented trade war between the two US allies last year after South Korean courts upheld a series of forced-labor claims against Japanese companies. The courts could as soon as next month rule on whether to liquidate corporate assets to compensate victims, something Tokyo would consider an escalation.

READ MORE: Japan, S. Korea reject report of WWII forced labor economic plan

Shigeki Takizaki, a senior Japanese Foreign Ministry official, dismissed complaints about the Hashima exhibit as “unacceptable” in a call with his South Korean counterpart last month. Japan will abide by its commitment to United Nations agencies, said Takizaki, the ministry’s director general of Asian and Oceanian Affairs.

The Japanese Embassy in Seoul didn’t respond to a request for comment about Park’s remarks on Thursday, a Japanese public holiday

Asked Wednesday to further explain Japan’s response, the foreign ministry in Tokyo said it wasn’t prepared to comment immediately. The Japanese Embassy in Seoul didn’t respond to a request for comment about Park’s remarks on Thursday, a Japanese public holiday.

“We will continue to endlessly discuss this issue, and we believe that this will also have an effect with our future exchanges with Japan, as well,” Park said Thursday. “To deny that is also being dishonest.”

The walled 6.3-hectare Hashima -- sometimes called Battleship Island -- was a site of undersea coal-mining in the 1880s and became a symbol of both Japan’s rapid Meiji modernization era and its subsequent colonial abuses. The conscription of hundreds of thousands of laborers from China, South Korea and other areas occupied between 1895 and 1945 remains a contentious issue with many of the country’s neighbors, with some surviving victims still pursuing claims.

ALSO READ: S. Korea court rejects attempt to repeal Japan sex slave deal

Although most South Koreans believe Japan hasn’t sufficiently apologized for its actions, many Japanese see past statements of regret as sufficient. Japan has taken in issue with South Korea’s description of the laborers as forced, preferring “former civilian workers from the Korean Peninsula.”

South Korea endorsed Hashima’s inclusion on the heritage list after Japan agreed to convey an “an understanding of the full history of each site.” But the information center in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district makes no mention of forced labor, instead citing one ethnic Korean and former Hashima resident saying there was no discrimination. The center also displays a wage stub of a conscripted worker from Taiwan, suggesting that such laborers had received payment.

“It depicts the situation as if South Koreans had voluntarily done this, as if there was nothing forced in the process,” Park said. “This is stating an outright lie. This is a serious distortion of history, and also a violation of what Japan had initially promised.”