This July 10, 2020 file photo shows vaccines in prefilled, single-use syringes following the inspection phase at the French pharmaceutical company Sanofi's world distribution center in Val de Reuil , France. (JOEL SAGET / AFP)

This July 10, 2020 file photo shows vaccines in prefilled, single-use syringes following the inspection phase at the French pharmaceutical company Sanofi's world distribution center in Val de Reuil , France. (JOEL SAGET / AFP)

Wealthy countries have already locked up more than a billion doses of coronavirus vaccines, raising worries that the rest of the world will be at the back of the queue in the global effort to defeat the pathogen.

Moves by the US and the UK to secure supplies from Sanofi and partner GlaxoSmithKline Plc, and another pact between Japan and Pfizer Inc, are the latest in a string of agreements. The European Union has also been aggressive in obtaining shots, well before anyone knows whether they will work.

Although international groups and a number of nations are promising to make vaccines affordable and accessible to all, doses will likely struggle to keep up with demand in a world of roughly 7.8 billion people.

READ MORE: 'Vaccine nationalism': Is it every country for itself?

The possibility wealthier countries will monopolize supply, a scenario that played out in the 2009 swine flu pandemic, has fueled concerns among poor nations and health advocates.

Sanofi and Glaxo intend to provide a significant portion of worldwide capacity in 2021 and 2022 to a global initiative focused on accelerating development and production and distributing shots equitably

The US, Britain, European Union and Japan have so far secured about 1.3 billion doses of potential COVID immunizations, according to London-based analytics firm Airfinity. Options to snap up additional supplies or pending deals would add more than 1.5 billion doses to that total, its figures show.

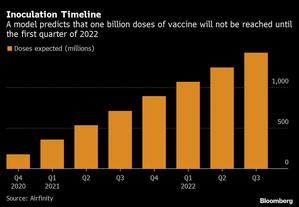

Inoculation timeline

“Even if you have an optimistic assessment of the scientific progress, there’s still not enough vaccines for the world,” according to Rasmus Bech Hansen, Airfinity’s chief executive officer. What’s also important to consider is that most of the vaccines may require two doses, he said.

A few front-runners, such as the University of Oxford and partner AstraZeneca Plc and a Pfizer-BioNTech SE collaboration, are already in final-stage studies, fueling hopes that a weapon to fight COVID will be available soon.

But developers must still clear a number of hurdles: proving their shots are effective, gaining approval and ramping up manufacturing. Worldwide supply may not reach 1 billion doses until the first quarter of 2022, Airfinity forecasts.

Investing in production capacity all over the world is seen as one of the keys to solving the dilemma, and pharma companies are starting to outline plans to deploy shots widely.

Sanofi and Glaxo intend to provide a significant portion of worldwide capacity in 2021 and 2022 to a global initiative that’s focused on accelerating development and production and distributing shots equitably.

The World Health Organization, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance are working together to bring about equitable and broad access. They outlined an US$18 billion plan in June to roll out shots and secure 2 billion doses by the end of 2021.

ALSO READ: Russia preparing mass vaccination for October

The initiative, known as Covax, aims to give governments an opportunity to hedge the risk of backing unsuccessful candidates and give other nations with limited finances access to shots that would be otherwise unaffordable.

Tangle of deals

Countries would need to strike a series of different agreements with vaccine makers to raise their chances of getting supplies, as some shots won’t succeed, a situation that could lead to bidding battles and inefficiencies, Seth Berkley, Gavi’s CEO, said in an interview.

“The thing we worry about most is getting a tangle of deals,” he said. “Our hope is with a portfolio of vaccines we can get countries to come together.”

Some 78 nations have expressed interest in joining Covax, he said. In addition, more than 90 low- and middle-income countries and economies will be able to access COVID vaccines through a Gavi-led program, the group said Friday. There’s still concern the rest of the world might fall behind.

“That is exactly what we’re trying to avoid,” Berkley said.

A lab technician fills a vial with a reagent while producing Corosure probe-free RT-PCR based COVID-19 Diagnostic kits in a laboratory at the Newtech Medical Devices facility in Faridabad, Haryana, India, July 15, 2020. (T NARAYAN / BLOOMBERG)

A lab technician fills a vial with a reagent while producing Corosure probe-free RT-PCR based COVID-19 Diagnostic kits in a laboratory at the Newtech Medical Devices facility in Faridabad, Haryana, India, July 15, 2020. (T NARAYAN / BLOOMBERG)

Biggest investment

AstraZeneca in June became the first manufacturer to sign up to Gavi’s program, committing 300 million doses, and Pfizer and BioNTech signaled interest in potentially supplying Covax.

The Trump administration agreed to provide as much as US$2.1 billion to partners Sanofi and Glaxo, the biggest US investment yet for Operation Warp Speed, the nation’s vaccine development and procurement program.

The funding will support clinical trials and manufacturing while allowing the US to secure 100 million doses, if it’s successful. The country has an option to receive an additional 500 million doses longer term.

The European Union is closing in on a deal for as many as 300 million doses of the Sanofi-Glaxo shot and is in advanced discussions with several other companies, according to a statement Friday.

“The European Commission is also committed to ensuring that everyone who needs a vaccine gets it, anywhere in the world and not only at home,” it said.

The US has invested in a number of other projects. Pfizer and BioNTech last week reached a US$1.95 billion deal to supply their vaccine to the government, should regulators clear it. Novavax Inc. earlier this month announced a US$1.6 billion deal, while the US earlier pledged as much as US$1.2 billion to AstraZeneca to spur development and production.

US investment to speed up trials, scale up manufacturing and boost vaccine development is “great news for the world,” assuming vaccines are shared, Berkley said.

“It helps drive the science forward,” he said. “On that I’m very positive. My concern is that we need global supply.”