Face mask-clad students have their temperature taken after arriving at their school compound in Phnom Penh on Sept 7, 2020, as schools reopen across Cambodia amid the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. (TANG CHHIN SOTHY / AFP)

Face mask-clad students have their temperature taken after arriving at their school compound in Phnom Penh on Sept 7, 2020, as schools reopen across Cambodia amid the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. (TANG CHHIN SOTHY / AFP)

One of the first cutbacks that many poor families consider during tough financial times is education for their daughters. During the pandemic with in-class learning shuttered, some girls in rural areas of Asia countries are being pushed to drop out.

The pandemic has decimated jobs and reduced household income, threatening to drag as many as 100 million people into extreme poverty

Lina, an 11th-grade student in Cambodia who dreamed of obtaining an accounting degree, is among them. Her parents want her to leave school and find work to help the family pay down its debt. Lina’s story was shared with Bloomberg by Room to Read, a non-profit organization that promotes literacy and gender equality in developing countries. The group changed her name to shield her identity.

To determine the impact of the virus outbreak on girls’ education, Room to Read conducted a survey of 28,000 girls in Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Laos, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Vietnam. It found that 42 percent of girls surveyed reported a decline in their family’s income during the COVID-19 pandemic and that one in two girls surveyed was at risk of dropping out.

ALSO READ: Australia heads for lowest virus count in three months

“When families can’t afford school and have to choose, they will often send boys,” said John Wood, founder of Room to Read. Financial hardships and cultural stereotypes about gender roles play a major part in keeping girls in less-developed countries from completing their education, he said.

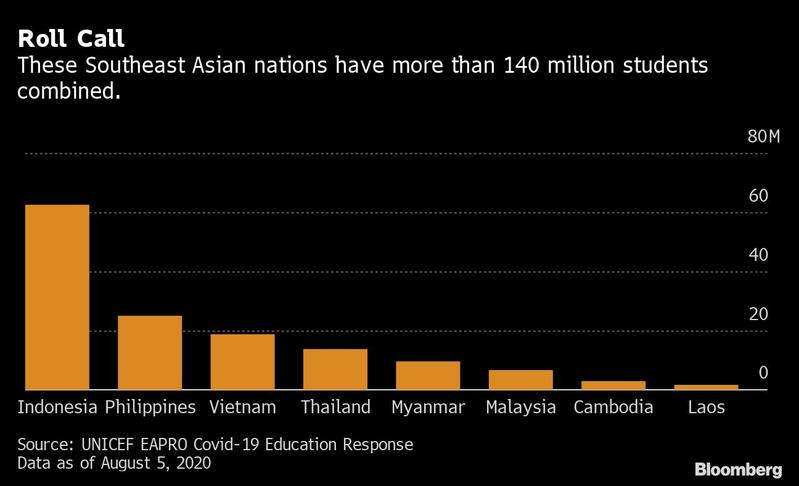

Although the full scope of the problem isn’t yet clear because many schools remain closed for in-person classes, groups that promote girls’ education including the World Bank and the United Nations’ agency UNICEF are closely monitoring the situation worldwide.

“More disadvantaged families are going to have particular struggles because of the economic impact. This will make it particularly difficult for them to send their children to school,” said Toby Linden, the World Bank’s education practice manager for East Asia and Pacific. “One of the lessons from the pandemic is the important role the families have in supporting their children’s education.”

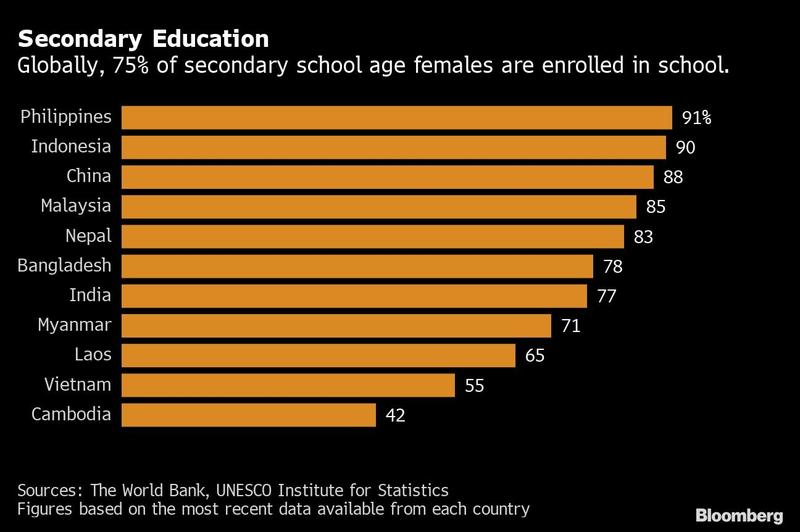

The pandemic has decimated jobs and reduced household income, threatening to drag as many as 100 million people into extreme poverty. As many as 20 million more secondary school-aged girls could be out of school globally, according to the Malala Fund, a non-profit organization that promotes girls’ education. In the Asia Pacific region, that would add to the 35 million girls and boys already not in school.

This is expected to exacerbate the education deficit for girls in poorer countries, where the rate of female secondary school enrollment was low before the pandemic. It risks setting back years of progress for girls’ education and gender equality in some of the world’s poorest nations.

The 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa showed how devastating a loss of income was to girls’ education. Poorer families needed their children to make money during the crisis, and children who found work were rarely encouraged to return to school when it reopened.

The female education deficit is one of the key factors hindering women’s workforce participation and their wages. An extra year of secondary school education for girls can increase their future earnings by as much as 20 percent. Barriers that prevent girls from completing 12 years of education and limited learning opportunities cost countries as much as US$30 trillion in lost lifetime productivity and earnings.

READ MORE: Virus brings curtain down on Cambodia shadow puppet theatre

“The worrying trend is that the reopening of schools doesn’t automatically mean that all children will be back in schools,” said Francisco Benavides, regional education adviser at UNICEF East Asia and Pacific. “The pandemic has a high economic impact for the region. If girls don’t have access to learning opportunities, it’s very likely that the families and society will be less able to adapt to economic shock.”

Educating girls also has been shown to lead to greater gender equality. For example, in Thailand, women hold 32 percent of senior management roles, compared with an average of 27 percent globally, according to Grant Thornton data published in 2020. They make up 24 percent of chief executives and 43 percent of chief financial officers. Although Thailand is an outlier, it shows what can be achieved when women are educated.

Though other countries in the region also have made progress in girls’ education in past decades, the virus means the region “will be going backward several years,” according to Benavides. “We’ll lose progress. The spillover effect will be massive because it may also impact the generation after this one. It can take us so many years to get back to where we were before. This won’t help the Asian economy.”