This undated photo shows Ippudo's 'Shiromaru Motoaji' ramen. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

This undated photo shows Ippudo's 'Shiromaru Motoaji' ramen. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

COVID-19 and social-distancing measures are forcing some owners of Japan’s tiny noodle shops to consider either pushing up their prices or pulling down their shutters.

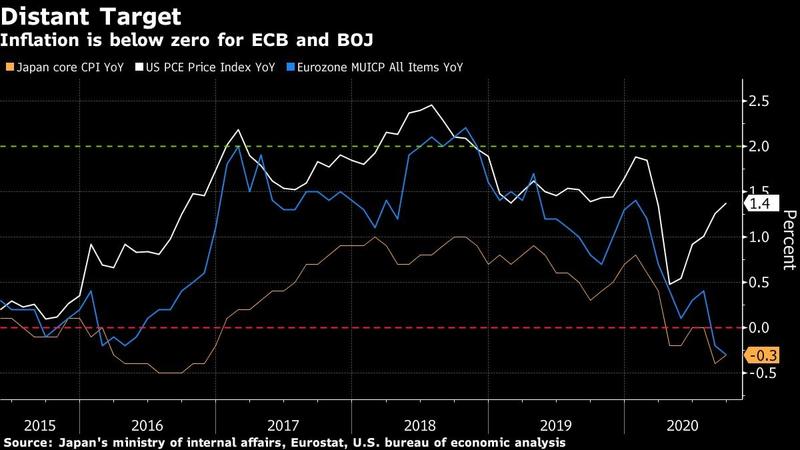

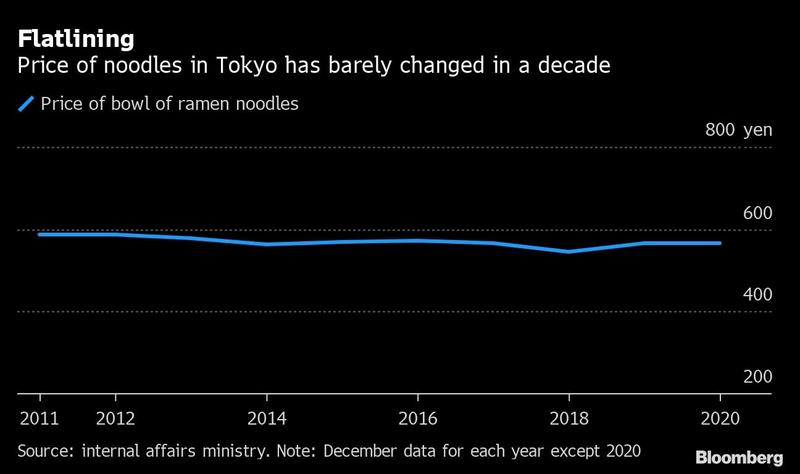

Their reluctance to raise prices speaks to a continuing aversion that prevails among companies and consumers in Japan, despite central bank efforts to change this mindset

The pandemic is upending a finely balanced business model that depends on serving quick, cheap fare to customers eating elbow-to-elbow.

While some proprietors are finally embracing the need to get creative with pricing, there are others who would rather shut up shop than force their regulars to swallow a more expensive bowl of ramen.

Their continued reluctance to pass on higher costs to customers partly reflects the continued sensitivity to price increases in a country that has struggled to shake off its lengthy experience of deflation.

Small ramen chain Kouraku Honpo is one of the many noodle shop operators looking for light at the end of the COVID- 19 tunnel.

For more than two decades, it has been serving wiry noodles with a pungent pork-bone broth at its branch in Tokyo’s Shimbashi district. Trade was roaring at the end of last year, with daily servings at the 26-seat joint sometimes nearing the 500 mark, according to store employee Yoshihisa Saito, 61.

ALSO READ: As Japan moves to revive its countryside, pandemic chases many from cities

This undated photo shows Kouraku Honpo's ramen shop in Shibuya. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

This undated photo shows Kouraku Honpo's ramen shop in Shibuya. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

COVID-19 changed these dynamics. The shop stayed open with shorter hours during a national state of emergency that continued in the capital until late May. Saito’s pay fell as much as 40 percent to keep the shop in business, but at no point did the store consider raising prices to cope with the new normal.

“A price increase was never an option because passing our burden onto customers would be totally unfair. Their finances could be under severe pressure too because of the virus, yet they are still coming to us,” Saito said.

On Aug 28 Kouraku Honpo closed its Shimbashi shop for good.

Small restaurants operators like Kouraku Honpo and hole-in-the-wall bars are among the businesses hardest hit by the pandemic as they struggle to price in social-distancing limitations on capacity and an increase in costs for virus-response measures. Shops that are also facing a sharp drop in demand are at most risk of going bust.

BOJ loan programs worth around US$1 trillion and large-scale government aid have helped reduce the overall number of bankruptcy filings in the economy between April and September from a year earlier. But the number of eateries going out of business has continued to rise, accounting for about 10 percent of bankruptcies, the highest among all types of business, according to Teikoku Databank.

From the beginning of the year through August, 1,221 restaurant operators have closed down, according to Tokyo Shoko Research data.

“Most Japanese businesses act on the premise that if the price of beer is 100 yen today, then it’s going to be a 100 yen tomorrow too,” said Tsutomu Watanabe, head of the economics department at the University of Tokyo. “To keep making that a reality, companies keep cutting costs. They’ll turn out some of the lights and they’ll keep a tight lid on wages. Their thinking becomes progressively inward looking.”

For some noodle bar owners just a small increase in prices would be enough to keep them in business, especially if neighborhood customers remain loyal.

Their reluctance to raise prices speaks to a continuing aversion that prevails among companies and consumers in Japan, despite central bank efforts to change this mindset. And with key consumer prices falling again, the prospect of a return to the deflation that ingrained that attitude can’t be ruled out.

Still, some restaurant owners are taking a fresh approach.

Kazuhisa Tanaka says a light bulb lit up in his head one gloomy night in May as he tried to figure out how to stay in operation while reducing the number of places in use at his 12-seat Japanese eatery.

In this undated photo, customers sit spacing apart for social distancing at Kouraku Honpo's ramen shop. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

In this undated photo, customers sit spacing apart for social distancing at Kouraku Honpo's ramen shop. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

“Simply cutting the number of customers without knowing when this pandemic will end is a loser’s game,” Tanaka said. He decided to raise the price of a lunch set to 1,500 yen (US$14) from around 1,000 yen during peak hours and lower the price to 800 yen--little more than half--after 2:30 pm.

“Adjusting prices has become my tool to deal with this crisis and this would never have happened without COVID,” Tanaka said.

Still, his staff objected to his dynamic pricing proposal, labeling it disloyal, and insisted he put a notice outside the shop making it clear it was his idea, not theirs.

READ MORE: Japan property funds on edge as Tokyo population drops amid virus

Tanaka isn’t alone in opting for dynamic pricing, a budding tendency that offers a glimmer of hope for policy makers seeking greater price movement in a country where inflation has been at or below zero since March.

Chikaranomoto Holdings, owner of Ippudo, one of the nation’s most popular noodle chains with shops around the world from New York to London, has seating capacity limited to about 60 percent as a virus-prevention measure.

Seeing revenue was still only around half its level the previous year after re-opening, the chain decided to raise the price of some of its set menus in late July, while offering new and cheaper ramen dishes for ultra price-sensitive customers the following month, according to Midori Nakamura, who works at the company’s public relations section.

“It’s becoming so hard to keep prices unchanged with the increasing costs and impact of COVID-19,” Nakamura said. “So what we do is give our customers a choice.”

In this undated photo, an Ippudo chef boils ramen noodles. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

In this undated photo, an Ippudo chef boils ramen noodles. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)