Morning commuters make their way to work at the Van Trung Industrial Park in Viet Yen district, Bac Giang province, Vietnam, on Oct 10, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Morning commuters make their way to work at the Van Trung Industrial Park in Viet Yen district, Bac Giang province, Vietnam, on Oct 10, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

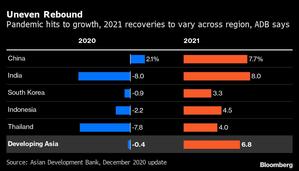

Asia’s head start in the economic recovery from COVID-19 is sending a warning to the rest of the world: inequalities exacerbated by the virus are unlikely to be reversed any time soon.

Even as the region’s rebound gathers pace, many workers who lost their jobs early in the crisis find themselves stuck in new positions with less pay. Economists caution that while a lasting shift toward the digital economy will create opportunities, it risks stoking divisions unless governments pour more investment into the workforce. The Asian Development Bank and International Labour Organization say as many as 15 million jobs for teenagers and young adults in the region could be lost this year.

Even as the region’s rebound gathers pace, many workers who lost their jobs early in the crisis find themselves stuck in new positions with less pay. Economists caution that while a lasting shift toward the digital economy will create opportunities, it risks stoking divisions unless governments pour more investment into the workforce

ALSO READ: OECD cuts global forecast, warns govts to maintain support

Asia is an important barometer for the world economy because it accounted for more than two-thirds of global growth in 2019 and is home to a majority of those between the ages of 15-24. It also began recovering from the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression earlier than much of the West, fueled by a rapid snap back in China.

“The big risk is that right now, especially when you interact the crisis with technological change, there’s a real risk that inequality gets worse,” said Aaditya Mattoo, the World Bank’s chief economist for the East Asia and Pacific region.

Even those who have been able to adapt are uncertain about the future. In Jakarta, Fanny Febyanti, 38, made an unlikely shift to catfish farming as she struggled to keep afloat a public relations business that she runs with her husband. It’s already clear to her that the recovery is going to take time.

“We are no longer able to give a fixed price for our services, instead we tell our prospective clients: how much money do you have and we’ll help you,” she says. “Survival is what matters now.”

ALSO READ: China's stable foreign trade to help boost global economic recovery

A degree in aquaculture meant she could turn to the catfish business to bring in money for food and tuition. She topped up that income by selling food online, all the while managing three kids at home. Two full-time staff members have been replaced by three interns.

“Life has changed,” she said. “We have had to slash our expenses.”

Stories like Febyanti’s are being replicated across Asia. Young workers, especially women and the poorest, have been hardest hit. The World Bank has warned that the COVID-19 shock is creating a class of “new poor” across East Asia and the Pacific with an additional 38 million people expected to fall below the poverty line.

China’s Recovery

In China, the world’s only major economy expected to grow this year, the job market is taking time to heal.

Before the pandemic struck, Mia Han, 29, was working in an online travel services company in Beijing. She lost her job in May as the pandemic hammered tourism, and finding a new one was more difficult than she expected.

ALSO READ: OECD: Global economy faces tightrope walk to recovery

After initially targeting Internet giants for work, she had to readjust her expectations, partly because of lower-than-expected pay. After four months, she landed a job with a consulting firm.

“In general, it fits my expectations in terms of work culture and duties,” Han said. “But I got the job at the expense of a pay cut and a career change.”

Manufacturing, which is leading the rebound as global demand surges for Asia’s inexpensively produced goods, faces a particular threat. An analysis by the International Monetary Fund shows that economic shocks trigger a surge in factories shifting to automated production, meaning Asia is at risk of a sizable hit as robot density quickly rises from a low base.

Manufacturing, which is leading the rebound as global demand surges for Asia’s inexpensively produced goods, faces a particular threat. An analysis by the International Monetary Fund shows that economic shocks trigger a surge in factories shifting to automated production, meaning Asia is at risk of a sizable hit as robot density quickly rises from a low base.

That’s one reason why policy makers, including central banks that have unleashed unprecedented support for their economies, warn that more will be needed to stop the inequality gulf from widening further.

Digital Economy

One bright spot: The crisis is accelerating development of a digital economy that will offer opportunities for agile tech-savvy workers, especially in e-commerce. It’s also offering a cushion for those already in the sector. Still, this year’s dislocation in the tech field has been difficult for some workers.

In Manila, web developer Maria Christa Felize Eala, 30, was forced to drop plans to work in Japan at a financial technology company amid strict curbs on travel. Instead of leaving for better pay and learning opportunities -- she had already tendered her resignation -- Eala was left stranded with a mortgage to pay and dwindling savings.

ALSO READ: IMF: Virus poses risks to fragile recovery in global economy

While the booming technology sector meant she found a new job after about five months, it doesn’t pay nearly as much as in Japan, where she says programmers and web developers earn at least triple what they do in the Philippines.

“Being in tech is an advantage given the shifts in the economy,” she said. “I know people who are finding it hard to find opportunities.”

While those with the right skills will be beneficiaries of the tech sector, those without them will be left behind. The impact of school closures in Asia will take years to become clear and the lack of social safety nets could make a dire situation worse, with girls particularly vulnerable.

Many young workers -- especially women -- are employed in the informal job market, meaning they don’t qualify for government stimulus and support packages, and could suffer a more prolonged dent in their incomes, said Priyanka Kishore, head of economics for India and Southeast Asia at Oxford Economics in Singapore.

A recruitment fair organised by Thailand's Ministry of Labor in Bangkok, Thailand, on Sept. 26, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

A recruitment fair organised by Thailand's Ministry of Labor in Bangkok, Thailand, on Sept. 26, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

“This also makes it difficult for the government to come up with targeted policies to support youth employment in emerging Asia,” she said.

Tackling the digital divide will define how Asia’s young workers can recover from the loss of education, jobs and the kind of social contact at a stage of their lives that is crucial to their development.

“We have a generation of students who have been impacted by lost schooling,” IMF Chief Economist Gita Gopinath told Bloomberg’s New Economy Forum on Nov. 18. “The jobs market is recovering in some places strongly but still if you look at low-income workers, if you look at women, if you look at young workers, they are just very hard hit.”

Vaccine Uncertainty

Optimism about effective vaccines is being offset by the complexities of distribution across Asia and especially in less-developed economies. That uncertainty is weighing on business owners and their employment and investment plans.

Ian Villaruel, 28, who runs an indoor cycling studio in Manila, notes that as gyms are allowed to again operate at limited capacity, many still prefer to work out at home. He’s concerned that wage cuts and more cautious consumers will reshape the sector.

“What I’m worried about is how soon people will be ready and willing to go out, because look at restaurants, they’re technically allowed to operate dine-in services, but they’re not full,” he said.

It’s a similar outlook for Sanyukta Garg, who with her husband Chirantan, runs a textile company from New Delhi. The business saw a drop of 80 percent in sales this year, compared with 7 percent to 8 percent annual growth before the pandemic hit. Garg is banking on the vaccine turning things around.

“If the vaccine isn’t there next year we will be at 50 percent of our sales,” she said of her textile company, Chandra Silks Pvt, which supplies major fashion brands. While Garg has stayed in business, it’s had to cut salaries of staff by 20 percent.

“Before the lockdown, we had plans to expand. We were looking to set up another factory,” she said. “Fortunately, we didn’t.”