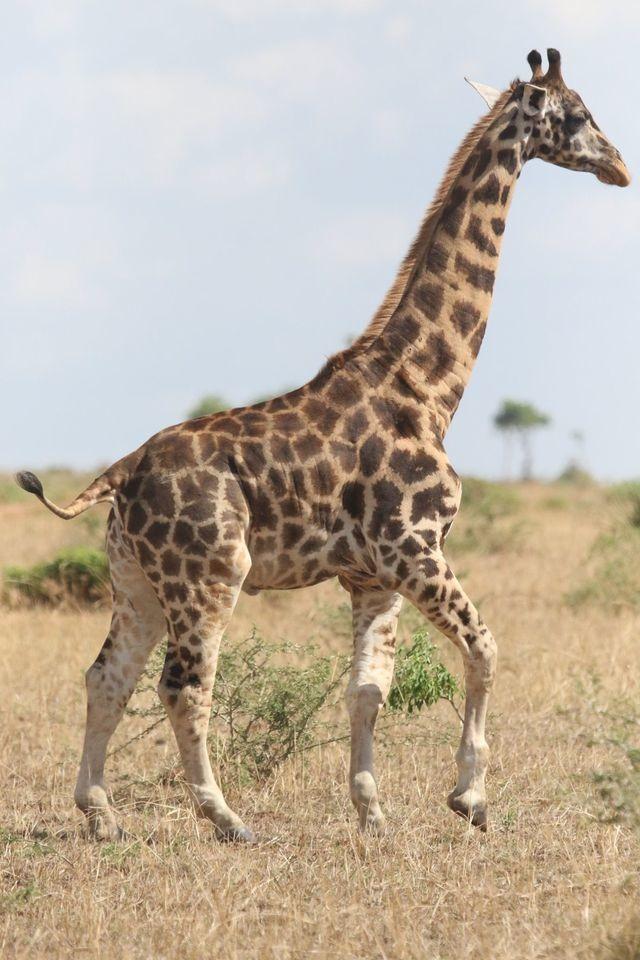

This photo taken on Jan 9, 2021, from the official Facebook account of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation shows one of the giraffe dwarves discovered in Africa.

This photo taken on Jan 9, 2021, from the official Facebook account of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation shows one of the giraffe dwarves discovered in Africa.

JOHANNESBURG - Being tall is the giraffe’s competitive advantage, giving it the pick of leaves from the tallest trees, so scientists were stunned to find two giraffe dwarves on different sides of Africa.

“It’s fascinating what our researchers out in the field found,” Julian Fennessy, co-founder of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, told Reuters in a videocall on Friday. “We were very surprised.”

Most giraffes grow to 4.5-6 meters, but in 2018, scientists discovered an 2.6-meter giraffe in Namibia. Three years earlier, they had also found a 2.8-meter giraffe in a Ugandan wildlife park

Most giraffes grow to 4.5-6 meters, but in 2018, scientists working with the foundation discovered a 2.6-meter giraffe in Namibia. Three years earlier, they had also found a 2.8-meter giraffe in a Ugandan wildlife park.

They published their findings in the British Medical Journal at the end of last month.

In both cases, the giraffes had the standard long necks but short, stumpy legs, according to the paper. Skeletal dysplasia, the medical name for the condition, affects humans and domesticated animals, but the paper said it was rare to see in wild animals.

ALSO READ: Giraffes move closer to endangered species protection

“Unfortunately there’s probably no benefit at all. Giraffes have grown taller to reach the taller trees,” Fennessy said. He added that it would most likely be physically impossible for them to breed with their normal-sized counterparts.

A giraffe of the "Masai" sub species forages on the plain at the Ol Kinyei conservancy in Maasai Mara, in the Narok county in Kenya, on June 23, 2020. (TONY KARUMBA / AFP)

A giraffe of the "Masai" sub species forages on the plain at the Ol Kinyei conservancy in Maasai Mara, in the Narok county in Kenya, on June 23, 2020. (TONY KARUMBA / AFP)

Numbers of the world’s tallest mammal have declined by some 40 percent over the past 30 years to around 111,000, so all four species are classified by conservationists as "vulnerable".

READ MORE: Kenya's only white female giraffe killed by poachers

“It’s because of mostly habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, growing human populations, more land being cultivated,” Fennessy said. “Combined with a little bit of poaching, climate change”.

But conservation efforts have helped numbers start to recover in the past decade, he added.