In this Feb 22, 2011 photo, anti-government protesters destroy a vehicle belonging to government supporters during a protest outside Sanaa University demanding Yemen President Ali Abdullah Saleh's ouster. (AHMAD GHARABLI / AFP)

In this Feb 22, 2011 photo, anti-government protesters destroy a vehicle belonging to government supporters during a protest outside Sanaa University demanding Yemen President Ali Abdullah Saleh's ouster. (AHMAD GHARABLI / AFP)

SANAA/TAIZ, Yemen - Ten years after joining an uprising in Yemen against autocratic rule and an economy in shambles, the same activists find themselves on opposite sides of a war that has pushed the country to the brink of famine with dim prospects for peace.

More than 2,000 people died in the uprising in Yemen before Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2012 yielded to pressure from the US and Gulf Arab states to step down

Ahmed Abdo Hezam, 35, a fighter with government forces known by his nom de guerre Ahmed Abu Al-Nasr, had been a university graduate in the agro-industrial city of Taiz when he first joined youth-led protests that ended Ali Abdullah Saleh’s 33-year rule.

Even back then some 40 percent of Yemen’s population lived on less than US$2 a day and a third suffered chronic hunger. Jobs were scarce and corruption rife. The state was facing a resurgent Al Qaeda wing and rebellions by the Houthis in the north and separatists in the south.

“When we joined the uprising it was like a breath of air. They tried to drag us into violence ... but we remained peaceful,” said al-Nasr who like many resented jobs cronyism in the public sector, the biggest employer.

ALSO READ: Yemen's disabled people wish for normal life

More than 2,000 people died in the uprising before Saleh in 2012 yielded to pressure from the United States and Gulf Arab states to step down. He was the fourth autocrat to be toppled in the “Arab Spring” unrest that first began in Tunisia.

Riyadh and Washington hoped former Saleh deputy Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi would improve the government’s legitimacy and oversee a transition to democracy. Instead it disintegrated.

The Houthis, enemies of Saudi Arabia and friends of Iran, partnered with erstwhile foe Saleh to seize the capital, Sanaa, and ousted Hadi’s government in late 2014, triggering a Saudi-led military coalition backed by the West to intervene.

Al-Nasr, a poet with four children, joined government forces when the Houthis, who later killed Saleh when he turned on them, entered Taiz, which is still effectively under siege.

“We did not think the uprising would lead to this,” said al-Nasr, who has seen comrades die, his home destroyed and family scatter. “We were forced to take up arms to defend ourselves.”

“I hope with all my heart the war ends...that weapons are laid down and all factions sit at the table.”

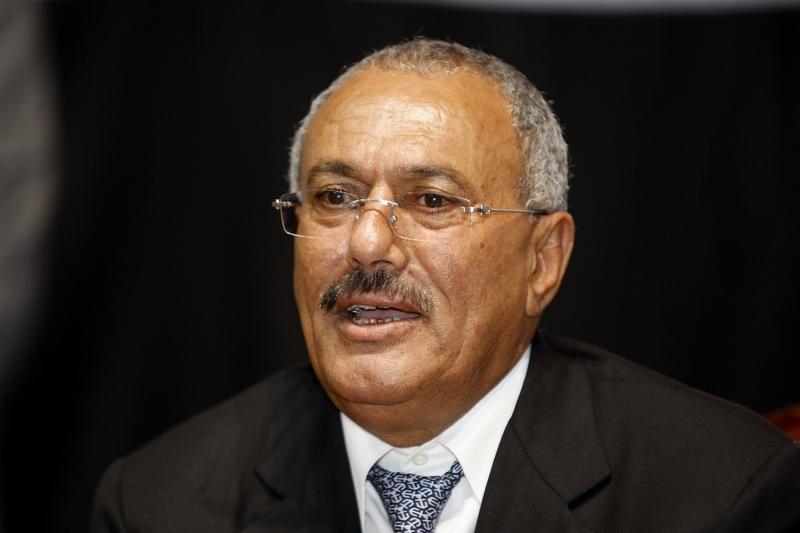

This Feb 20, 2011 photo, shows Yemen's late deposed president Ali Abdullah Saleh addressing a gathering of supporters in the capital Sanaa. (PHOTO / AFP)

This Feb 20, 2011 photo, shows Yemen's late deposed president Ali Abdullah Saleh addressing a gathering of supporters in the capital Sanaa. (PHOTO / AFP)

Self-determination

The war has killed more than 100,000 people and pushed millions to the verge of starvation. Now 80 percent of the population, or some 24 million, need help and are vulnerable to disease, first cholera and now COVID-19.

Ali al-Dailami, a rights defender briefly detained under Saleh’s rule who is now Houthi deputy minister of human rights, joined the uprising in “Change Square” in Sanaa in the hopes it would lead to a state representing all.

Speaking to Reuters in the square, al-Dailami recalled the early days of the revolution, and lamented its results.

“At times we thought we would not live to see the sun rise because of the threats and (pro-Saleh) soldiers and hoodlums,” he said. “We wanted to move from a failed state, we wanted to break the impasse.”

He saw the Gulf initiative that ushered in Hadi as interference that “killed the revolution’s principles”.

“We wanted real change, not to repackage the old system as democracy.”

Dejected, Dailami left Sanaa for Cairo but returned as the Saudi-led coalition bombarded and blockaded Yemen, killing thousands of civilians and exacerbating hunger.

Once rebels largely kept at bay, the Houthis now hold northern Yemen, from where they have repeatedly attacked Saudi cities with missiles and drones. The government is based in the south where separatist seek more power.

In this Feb 17, 2019 photo, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Yemeni journalist, politician and human rights activist Tawakkol Karman smiles as she attends a panel discussion at the 55th Munich Security Conference (MSC) in Munich, southern Germany. (THOMAS KIENZLE / AFP)

In this Feb 17, 2019 photo, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Yemeni journalist, politician and human rights activist Tawakkol Karman smiles as she attends a panel discussion at the 55th Munich Security Conference (MSC) in Munich, southern Germany. (THOMAS KIENZLE / AFP)

West must act

Rights advocate Tawakkol Karman, a 2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner for her role in Arab Spring protests, was abroad when the Houthis seized Sanaa and has not returned. She is a vocal critic of the group and of the Saudi-led coalition, accusing them of repressing democratic change in the region.

“After the revolution we lived three of the most beautiful years ever...we were days away from the referendum of the constitution and holding multiple elections,” she said, blaming the Houthi coup, the war and Western inaction for what followed.

Karman urged new US President Joe Biden to “fulfil his commitment and his promises to end this war in Yemen” and to halt arms sales to Saudi Arabia and its ally the United Arab Emirates.

READ MORE: Yemen aid groups call on US to revoke Houthi terrorism designation

In the southern port of Aden, civil engineer Waddah al-Hariri, 49, hopes the United Nations can revive stalled peace talks. He has moved his family to Hodeidah, then Sanaa and back to Aden to escape fighting.

A member of the Socialist Party that ruled South Yemen before unification with the North under Saleh in 1990, he believes the aims of the uprising he joined are still possible.

“Building peace is the priority now, and then a new constitution,” he said.

In this Nov 25, 2011 photo, Yemenis protest against President Ali Abdullah Saleh during a rally after the weekly Friday noon prayers in Sanaa. (GAMAL NOMAN / AFP)

In this Nov 25, 2011 photo, Yemenis protest against President Ali Abdullah Saleh during a rally after the weekly Friday noon prayers in Sanaa. (GAMAL NOMAN / AFP)