Seiko Hashimoto, president of the Tokyo Olympic Organizing Committee, adjusts her face mask during a news conference in Tokyo, Japan on Feb 18, 2021. The committee appointed Hashimoto, one of Japan's most-celebrated female Olympians, as its new chief after her predecessor stepped down over his sexist remarks. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Seiko Hashimoto, president of the Tokyo Olympic Organizing Committee, adjusts her face mask during a news conference in Tokyo, Japan on Feb 18, 2021. The committee appointed Hashimoto, one of Japan's most-celebrated female Olympians, as its new chief after her predecessor stepped down over his sexist remarks. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

The shuffling of senior Olympic leadership positions in Japan has put a spotlight on an uncomfortable truth in the country: After years of public statements in support of women in leadership, there still don’t seem to be enough to go around.

In its search for a replacement for Yoshiro Mori, 83, who resigned last week after disparaging women for talking too much, the Tokyo Olympic Organizing Committee landed on former athlete Seiko Hashimoto. But she already had a job in the cabinet, as Minister for the Olympics and held the gender equality portfolio.

Japanese women face a number of obstacles to professional advancement, including a culture of long working hours, which makes it difficult for Japanese women with families to take on senior positions

She eventually resigned those roles, forcing a new scramble to fill her shoes. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga tapped Tamayo Marukawa, who has served as Olympics minister in the past.

“Having to cannibalize the cabinet to find a woman to save the Olympics from clueless octogenarians speaks volumes about the low status of women in Japan,” said Machiko Osawa, a professor who researches labor economics at Japan Women’s University. “They are underrepresented across the board due to the discriminatory policies and attitudes that Mori and his powerful defenders put in the limelight.”

ALSO READ: Tokyo 2020 organizers say new head needs deep understanding of gender equality

Though the numbers vary across sectors, Japan overall is way behind the target set by the government in 2003 of having women take 30 percent of management posts in all fields by 2020. Today there are few if any women in the wings when senior positions open up.

Politics is among the most stubbornly male-dominated fields, with women making up less than 10 percent of lower house lawmakers in Suga’s own Liberal Democratic Party, and only two of his his 20-strong cabinet.

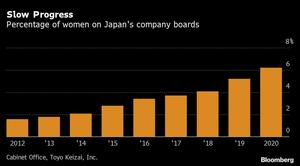

This Bloomberg graph dated Feb 19, 2021 shows the percentage of women on Japan's company boards in 2012-2020.

This Bloomberg graph dated Feb 19, 2021 shows the percentage of women on Japan's company boards in 2012-2020.

The private sector is by some measures even more lopsided than government. On the boards of Japanese listed companies, women held just 6.2 percent of director positions, up from 1.6 percent in 2012, according to the Cabinet Office Gender Equality Bureau. Worldwide, women hold around 20 percent of board seats; among Hong Kong Special Administrative Region-listed companies, they comprise 13 percent.

Japanese women face a number of obstacles to professional advancement, including a culture of long working hours, which makes it difficult for Japanese women with families to take on senior positions. Japanese men do less housework than their counterparts in any other member country of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), often increasing the burden on their partners.

Efforts to entice more women into the workplace and keep them there have had some success - larger numbers are entering the career track of the bureaucracy, for example, though few have cracked the senior ranks. More typically, women end up in poorly paid part-time positions after having children.

Noriko Mizoguchi, who took silver in judo at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, called for more women in leadership positions across the country’s sporting bodies, not just on the 2020 Organizing committee - a move that would, in turn, fill the pipeline of future Hashimotos or Marukawas.

READ MORE: Tokyo strives to keep Olympic dream alive amid doubts

“Women are just as active as men in the Olympics recently, but I can’t say there’s an appropriate number of women in management,” said Mizoguchi, now a professor of sports science at Japan Women’s College of Physical Education. “Gender equality is still a work in progress.”