With its philosophy of quantity over quality, the streaming giant could be setting a new standard for filmmaking, and it’s not a good one. Elizabeth Kerr peels away the shiny veneer.

There’s a joke floating around these days, about how if you have a half-baked idea for a blandly entertaining action movie, and you can’t get the “major” players to read your script, Netflix will more or less hand you a check. Whether that’s a good thing or not is a subjective determination, but it’s also one that filmmakers, producers, critics and, most crucially, audiences have lately been wrestling with especially vigorously.

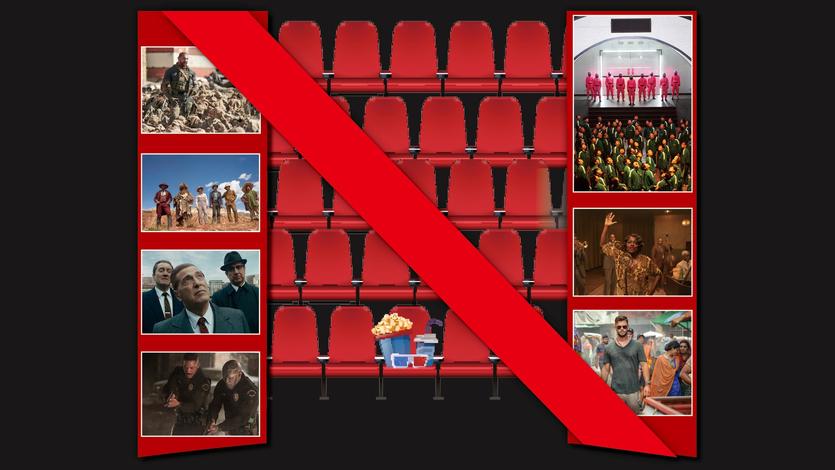

The Irishman (2019). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Irishman (2019). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

It’s been a hard couple of years for the movies. Since the start of the pandemic in early 2020, film and television production centers have been in and out of lockdown, and movie theaters have been shuttered. Then reopened. Then shuttered again. American cinema chain AMC Theaters and UK-based Cineworld narrowly avoided bankruptcy, and a whopping 70,000 Chinese cinemas were closed in January 2020, killing the lucrative Lunar New Year movie season. Here in Hong Kong, the venerable UA Cinemas went into liquidation a year ago.

Army of the Dead (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Army of the Dead (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

All of which is not to say there haven’t been new movies to watch. Scads of completed films were postponed in 2020 — including some major tentpoles like Wonder Woman 1984 — but many eventually gave way to the streaming route. In 2020, few would have guessed that we’d still be here two years on, but distributors have ramped up their streaming capabilities, and in many parts of the world, the online medium has become the norm.

The Ridiculous 6 (2015). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Ridiculous 6 (2015). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Netflix remains king of the streamers, and its voracious appetite for content had it purchasing and greenlighting filler that would have rightfully fallen off the radar (or gone back into development) before the pandemic, and before competitors with equally deep pockets — and most importantly, decades’ worth of IP — got into the streaming space. Amazon Prime, Apple TV+, Disney+ and (the only one not yet available in Asia) HBO Max are now options, with the latter two reclaiming content previously licensed to Netflix that had initially driven its subscriber base.

Bright (2017). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Bright (2017). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

That same voracious appetite famously saw the streamer operating in massive debt until last year, so that it could build its own library. It threw money at talent: $300 million at producer Ryan Murphy for five years; $150 million for Shonda Rhimes over four years, a deal that was recently expanded thanks to the success of her series Bridgerton (2020); and a mind-boggling four-film agreement with Adam Sandler for $250 million.

Extraction (2020). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Extraction (2020). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Made for laptop

The Sandler deal is perhaps the most indicative of why Netflix can be seen as a threat to movies. Last June, producer Kenya Barris, who abandoned a $100 million deal with Netflix, told The Hollywood Reporter: “I just don’t know that my voice is Netflix’s voice. The stuff I want to do is a little bit more edgy, a little more highbrow, a little more heady, and I think Netflix wants down the middle, … Netflix became CBS,” — a reference to the American broadcaster known for being bland, safe and stodgy.

Red Notice (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Red Notice (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

You can add “algorithmic” to descriptors for Netflix. Since it started a concerted push into original programming around 2015, the streamer has run hot and (mostly) cold with critics, if not with audiences. Over the last couple of years, Netflix has demonstrated a bizarre devotion to mediocrity and inoffensiveness. It’s as if it were developing by data analytics rather than creator vision, in a laboratory where technicians assemble the right movie star, globe-trotting story and harmless plot elements — and while that’s good for puffing up a library, it’s bad for movies. This may be the way many movies get made — Marvel’s own tried-and-true formula avoids filmmaker voice in favor of mass-market appeal — but the mathematics involved are helping drive the last nail into the story-driven-film coffin.

Lupin (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Lupin (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

When Netflix is dangling hard-to-come-by funding, it can be hard to resist. Martin Scorsese took The Irishman (2019) to the streamer after traditional studios dropped out. The film was OK; far from Scorsese’s best (though to say so is blasphemy). Did Zack Snyder’s Army of the Dead (2021) bring anything new to the zombie table? No, but it was OK. And that’s just it: Netflix is reveling in “OK”; nothing has been great. It’s what separates Netflix from its streaming rivals now. The films Disney+ and HBO Max are sending to streaming were created with a theatrical eye — Mulan (2020) and Dune (2021) are ambitious and cinematic. Netflix is a streamer first. The medium makes a difference.

Squid Game (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Squid Game (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Miraculous mediocrity

Netflix came out swinging in 2015 with Sandler’s The Ridiculous 6, a critically panned, comedic American Western it said was streamed more than any other film in Netflix’s history, justifying the aforementioned production deal and confirming Sandler’s ongoing appeal. David Ayer’s fantasy cop thriller Bright (2017) was notable mostly for its clumsy social commentary and lumpy visuals, but following a critical bashing, Netflix Co-CEO Reed Hastings told Variety: “Critics … are an important part of the artistic process but are pretty disconnected from the commercial prospects of a film. If people are watching this movie and loving it, that’s the measurement of success.” Hastings and Co have picked up that ball and run with it.

Roma (2018). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Roma (2018). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Also a hit was the Chris Hemsworth-starring actioner Extraction, an early pandemic-era success. Dropping on the platform in April 2020 — when the latest James Bond outing, No Time to Die, had been delayed — it was the only game in town. But Extraction was a by-the-numbers, orange-filtered, vaguely racist bit of B-movie schlock that back in the 1980s and ’90s would have been a straight-to-video afterthought. Netflix claimed the film was seen by 90 million households in its first month of release, making it its biggest premiere to date at the time. Needless to say, there will be a sequel, and possibly a franchise.

The Power of the Dog (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Power of the Dog (2021). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The custom-made junk that fills the hours and proves the business model for shareholders (a crucial element when subscriber numbers are stagnating) spiked in 2021 and gave rise to the “Netflix film” tag, now used to describe forgettable, middle-of-the-road diversions. The apex predator of those, so far, is Rawson Marshall Thurber’s lazy action-comedy Red Notice. In it, Gal Gadot, Ryan Reynolds and Dwayne Johnson cover all demographics as they hunt for a priceless artifact. It’s a cynical film that aims for National Treasure heights, and believes its own empty calories to be worthy of Michelin stars. Unsurprisingly, Netflix announced that Red Notice was the fifth-most streamed title of 2021, and that there will be two more, already in production.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

To be fair, Netflix has its strengths. It has no rivals in its ability to showcase international television drama. French heist drama Lupin (2021), starring Omar Sy; German time-travel thriller Dark (2017); and, most obviously, South Korean class-based thriller Squid Game (2021) can all thank the platform for their success, as can cross-border audiences for access. Similarly, when it comes to distribution, scores of truly great films have benefited from the platform’s global reach: the musical Tick, Tick … Boom! (2021), Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020), Alfonso Cuarón’s Oscar-winner Roma (2018) and Oscar frontrunner The Power of the Dog (2021), among dozens of others.

None of this is to say that so-called empty calories don’t have their place: We all love McDonald’s from time to time. And Netflix’s agreeability is a symptom of traditional production processes that are failing the mid-budget film and emerging filmmakers, not a cause. But by feeding the beast, it’s entrenching and legitimizing entertainment by algorithm — and that’s the antithesis of what the movie should be.