The world’s latest technology sensation seems to be a threat to the human workforce, but it may still be a long way off before this could become a reality. Wang Yuke reports from Hong Kong.

‘First love, it’s a flame that never dies. A memory that lingers on in my heart and mind. First love, it’s a moment I’ll always treasure. With a smile that shines and a love that’ll last forever …”

You may assume they’re just saccharine lyrics bobbing and flowing on the giddily catchy chord progressions laced with a string of cheery melodies. But, you would be dead wrong if you were to think it’s the brainchild of a human artist by default. In fact, it’s a masterpiece by ChatGPT (Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer) — an intelligent chatbot created on large language models and a product of generative artificial intelligence.

Hong Kong’s first GPT-assisted music single, First Love, by independent music platform Jamintheroom Entertainment, debuted in April. Adam Tam, the record producer, without feeling even a bit menaced by ChatGPT’s music genius, says ChatGPT’s emergence only amplifies the importance of human involvement in music composition or, precisely, the emotional embellishment that can only be fulfilled by human artists.

“Music improvisation is an experience-based affair, and a song without emotional heft can hardly be heart-stirring,” he says.

ChatGPT — the latest technology sensation with its astonishingly versatile capability of performing jobs on instructions — has set tongues wagging and touched billions of hearts around the world.

Its “wow” effect aside, the advent of ChatGPT has sparked fears among all walks of life that the chatbot, or other AI technologies, would make humans redundant in the workforce. While occupations that tend to be “menial” and “repetitive” may well be among the first to be relegated to obscurity, it could still be a long way off before ChatGPT could replace professionals in creative industries, only because it has no emotional intelligence and intuition — the very basis for arts to electrify the audience and strike an emotional chord.

The chords rendered by ChatGPT are merely the backbone, or structure, of the piece of music. “It can’t stand without human engagement, such as modifying the tempo, tinkering with the dynamics, refining the lyrics, choosing the most suitable instrument for the desired mood, and adding a vocal touch in the final recording,” explains Tam.

The human voice texture and all the emotionally charged finishing touches by the human artist are essential meat for the GPT-generated chords’ “skeleton”, says Edward Sung, founding director of Jamintheroom. ChatGPT masquerades as an entity with the soul and emotions, but it’s actually a faux emotion, thanks to “social programming”, argues Sung, referring to the sociological process of making individuals to respond in a manner widely approved by society. “Arts is a personal venture that only comes alive with an individualized firsthand element,” he says.

ChatGPT’s flat, scripted creation (above) contrasts with Chan’s soulful and heartfelt expression in the 300-word letter writing competition, showing that artificial intelligence can’t outwit its human creative counterparts. (WANG YUKE / CHINA DAILY)

ChatGPT’s flat, scripted creation (above) contrasts with Chan’s soulful and heartfelt expression in the 300-word letter writing competition, showing that artificial intelligence can’t outwit its human creative counterparts. (WANG YUKE / CHINA DAILY)

Neuron networks vs brain

To make sense of ChatGPT’s limitations — emotionally lame and inept — we need to reverse-engineer how ChatGPT is developed.

The underlying technology of ChatGPT, or artificial intelligence in general, involves artificial or simulated neural networks that mimic the way human brains aggregate knowledge and form ideas through signals and among biological neurons. By its very nature, ChatGPT is a programmed tool trained on a colossal pool of existing data to identify patterns and tease out correlations that enable it to generate answers and make predictions.

However, it’s too reductive to equate the neural networks that ChatGPT or AI, in general, is modeled on, with the complex biological networks that support human brains to function. In other words, while AI can simulate some of the processes involved in human brain functions, it’s far from capturing and replicating the complexity and nuances of human thought and behavior, which are attributed to layered life experiences and thus emotional wisdom or, colloquially, “street smarts”.

“In the human brain, knowledge and information are introduced through sensory input and are transmitted through neuron networks via electrical and chemical signals. The processing of such information involves complex interactions among neurons that are shaped by experience and learning. Neurons form connections with each other and strengthen or weaken these connections based on the frequency and timing of their activation,” says Ken Ip, chairman of the Asia MarTech Society.

Machine learning, no matter how “deep” it’s touted to be, is far removed from human learning in that the latter involves the relentless input of fodder from experiences, including “sensory input, social interactions, and a lifetime of accumulated knowledge and expertise”, says Ip. “This allows humans to draw on a much wider range of information when generating ideas and solving problems, and to approach problems in a more intuitive way.”

A complex and multifaceted ability, and emotional human intelligence that signals our superiority over other species, are rooted in both “nature and nurture”, says Sreedev Sharma, founder of Sociobits, suggesting that AI is blessed with nurturing as it can be trained, but without nature.

The difference in the learning approach between ChatGPT and humans evokes the question: Does the emotional inadequacy in ChatGPT and other chatbots prevent them from producing creative works or results that emotionally resonate with the audience?

Ip’s answer is an absolute “yes”. “Its incapacity for broader contextual understanding and intuition that comes with human personal experience and expertise can handicap its imagination and artistic license to generate creative works that are emotionally relatable to the audience,” he says.

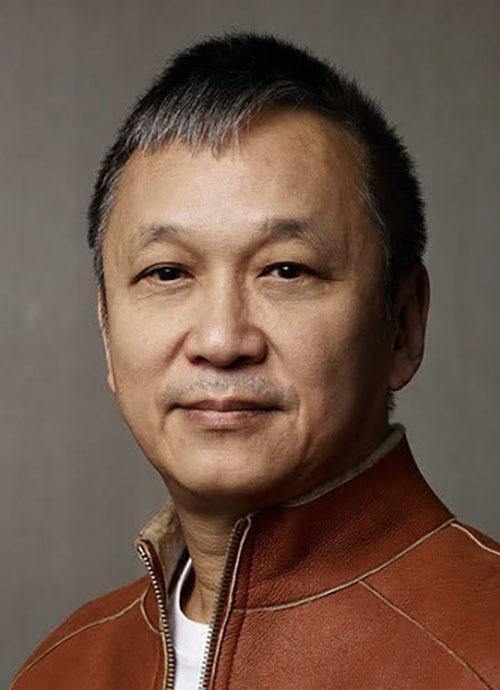

A snippet of dialogue in a film script or novel generated by AI, solely based on existing data sets and content gleaned from the internet and cobbled together, may well be seen as clunky, awkward, stilted, dry and hollow after being chewed over and scrutinized, and which the audience can be hardly identified with. Few people could have a better say in that than renowned Hong Kong film director Teddy Chan Tak-sum.

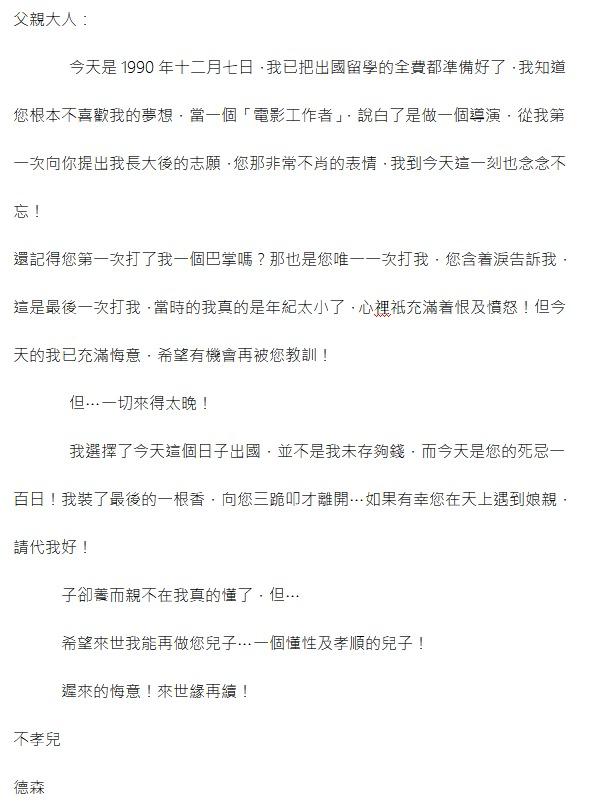

ChatGPT’s flat, scripted creation contrasts with Chan’s soulful and heartfelt expression (above) in the 300-word letter writing competition, showing that artificial intelligence can’t outwit its human creative counterparts. (WANG YUKE / CHINA DAILY)

ChatGPT’s flat, scripted creation contrasts with Chan’s soulful and heartfelt expression (above) in the 300-word letter writing competition, showing that artificial intelligence can’t outwit its human creative counterparts. (WANG YUKE / CHINA DAILY)

Emotional alienation

After Chan and ChatGPT were brought together and challenged to write a 300-word letter “from a son to his father before he left his hometown to pursue a filmmaking career in Teddy Chan’s style”, he was more convinced that AI can’t outwit its human creative counterparts.

A loose translation of Chan’s version is:

“Today is Dec 7, 1990. I’ve got everything ready for my study abroad. I know you loathe my decision to pursue the film path.

“Do you remember the first and only time you slapped me? You wept. You promised it would be the last time. I was then filled with hatred and rage. But now, I’m overcome with nothing but guilt and remorse. I chose today for my departure not because I’ve saved enough money but because it’s the 100th day of your death. I lit the last incense and kowtowed to your portrait before I left. If you meet mother in heaven, please send my best regards to her.

“I hope I could be your son again in the next life — a sensible, obedient, respectful and filial son! Belated remorse. Till we meet again in the next life.

“Your unfilial son”.

While ChatGPT’s rendition perfectly ticks all the boxes fed in the prompts, it’s flat and mediocre in terms of its tone and effect of storytelling, says Chan. It reads more scholarly, scripted and programmed from an arbitrary collection of sources, and less spontaneous, fluid and heartfelt, which leaves a void at the core, emotionally alienating the readers, he explains.

Literary prowess aside, the author’s personal experience would anchor him in the right frame of mind or memory to express through language, insists Chan. “The dearth of personal, firsthand experience in ChatGPT explains why nuanced, granular and vivid accounts are absent in its (son-to-father) letter. When you read it, you can barely feel it because the lines are just skin-deep without the power of offering a feeling of deja vu in your life,” says Chan.

Rather than a total fabrication, Chan’s letter was inspired by his true tales with his father. “My father’s denial of my film director dream is real. He did slap me in the face. I do beat up myself for being too rebellious. So the ‘letter’ I wrote is very faithful to my experience. It’s a true-to-life personal story that affords the letter flesh and bones, that prompts an emotional attachment and resonance among readers in stark contrast to the unrelatable AI rendition without truly individualized genesis,” says Chan, demanding that arts exist for emotional correspondence.

“I can’t imagine a day when ChatGPT can supplant writers, screenwriters and creatives in the film and TV industry because the chatbot, without emotion and sentience, is no parallel to humans,” he adds.

Recently, an AI-generated photo titled Pseudomnesia: The Electrician won the creative open citatory at the Sony World Photography Award in the guise of a human photographer’s entry. It not only grabbed headlines, sending shivers down the spine of the creative industry, it triggered a discourse on the future of photography and other creative genres.

Is the AI-made photography creative enough for the prize? To Siau Keng-leng, head professor at the Department of Information Systems at the City University of Hong Kong, the answer is in the affirmative.

“Creative is creative”, and the creative industry shouldn’t discriminate between human and AI iterations. What really matters is how artists are warming up to the powerfully capable AI technologies, adapt to the machine-human relationship, which is increasingly leaning toward symbiosis, and embrace it with an open mind, instead of dwelling on the question of being supplanted by ChatGPT or not, he argues. Encounters with AI are “inevitable”.

Teddy Chan Tak-sum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Teddy Chan Tak-sum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The genie is out the bottle

As ChatGPT and other large language models improve themselves at an exponential rate and pace, their enhanced intelligence will bring about a reshuffle in creative jobs by introducing new job descriptions and transforming creatives into more-efficient performers.

To Tam, the whole process of “teasing” a piece of chords and lyrics out of ChatGPT was fun-packed — a thrill akin to unboxing — as it spat out a barrage of versions within just 30 minutes, which would take at least a week for a human composer. While some of ChatGPT’s results didn’t cut the lyrics either because they were clumsy or the dynamics were unhinged, the rest were “surprisingly brilliant”, says Tam, who was even inspired by the chatbot’s peppy tunes.

“My initial intent was to create something exclusively with the piano for the mellow nostalgic vibe. But ChatGPT’s funky reference gave me the ‘eureka’ moment. It struck me as, ‘Ah, love songs can come with a choppy and zesty verve!’ So I threw the guitar into the mix.”

“We humans are a very subjective labor force, dictated by harbored bias or habits without knowledge,” says Tam. As a result, humans tend to go for the safest bet, he added.

It’s true that ChatGPT or AI has no visceral sentiment and sentience to its detriment. But on the flip side, when it’s used as an assistant or tool in artistic creations, it allows creatives an envelope-pushing mindset without being blinded by intrinsic or habitual bias and being stuck in a rut.

Now that AI can yield standard, run-of-the-mill musical pieces which can gain commercial success, human wannabes will have to develop an out-of-the-box bespoke musical lexicon and pathos if they are really eager to stand out.

Contact the writer at jenny@chinadailyhk.com