The guqin's melodic sound seems to embody the resonance of Chinese culture, Chen Nan reports.

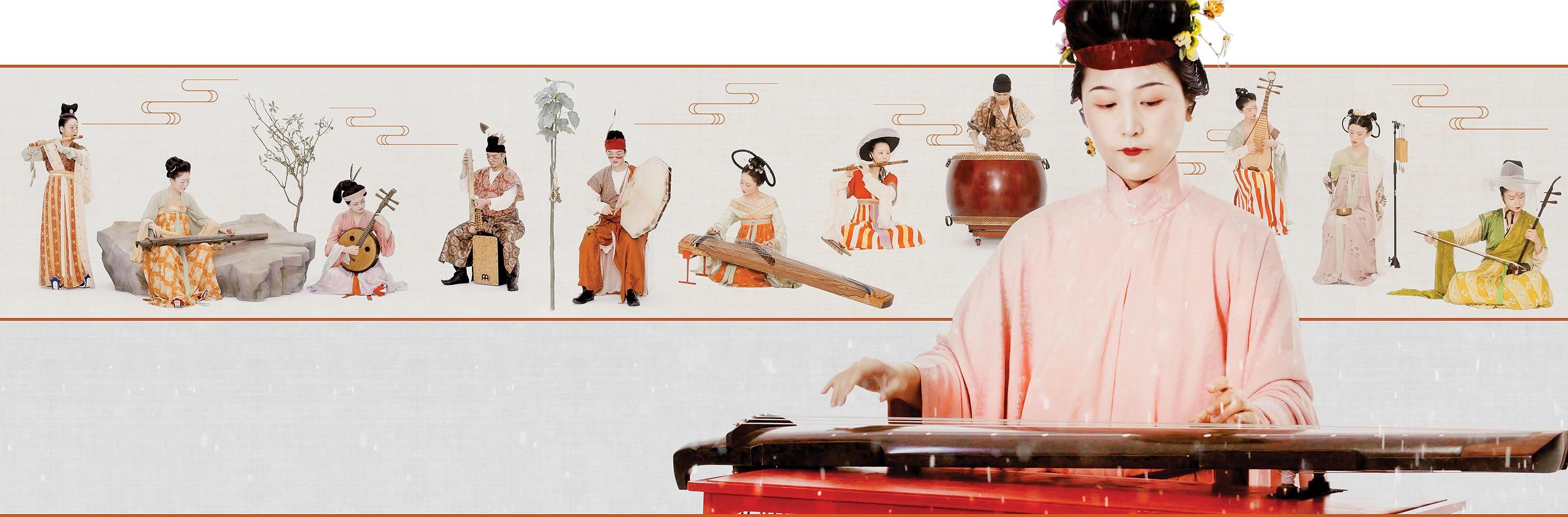

Zide Guqin Studio uses modern means to popularize the ancient zither, as well as other traditional musical instruments, among a younger audience. (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

Zide Guqin Studio uses modern means to popularize the ancient zither, as well as other traditional musical instruments, among a younger audience. (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

Editor's note: There are 43 items inscribed on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage lists that not only bear witness to the past glories of Chinese civilization, but also continue to shine today. China Daily looks at the protection and inheritance of some of these cultural legacies. In this installment, we discover why guqin, a musical instrument with a history spanning three millennia, still strikes a chord with Chinese music lovers.

When talking about the history of the guqin, Wu Wenguang, a virtuoso performer of the ancient zither, likes to quote a folktale about the legendary friendship between a musician and his biggest fan.

Such was the connection between performing and listening, which is linked by the guqin, an instrument that is endowed with the power to communicate the deepest feelings.

Wu Wenguang, guqin player

During the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), there was a musician named Yu Boya, who lived alone in a forest where he played the guqin. A passing woodcutter named Zhong Ziqi was intrigued by the sounds of the musical instrument and stopped to listen. Yu's playing conjured up various pictures in Zhong's imagination, such as clouds flowing and waterfalls plunging. They became good friends. After many years, when the woodcutter died, Yu decided to smash his instrument and never to play again because he knew that he would never again have someone like Zhong to so intuitively understand his music.

"Such was the connection between performing and listening, which is linked by the guqin, an instrument that is endowed with the power to communicate the deepest feelings," says Wu, 78. "When we talk about traditional Chinese culture, the guqin, which was played by many literati and other notables, is definitely at the core of this culture."

Indeed, the guqin — the favored instrument of Confucius — was an essential musical instrument of ancient China's educated elite. It was added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2008.

"The Chinese zither has existed for more than 3,000 years and represents China's foremost solo musical instrument tradition. Described in early literary sources and corroborated by archaeological finds, this ancient instrument is inseparable from Chinese intellectual history," the UNESCO website reads.

In April, when President Xi Jinping met with French President Emmanuel Macron, a classic guqin piece, High Mountain and Flowing Water, was played to celebrate the friendship and mutual understanding between the two countries.

The guqin and its music, with a history of 3,000 years, are kept alive thanks to the devotion of generations of musicians. Wu Wenguang (above), a virtuoso performer, has passed on his skills to his students, including Huang Mei and Sun Haopeng. (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

The guqin and its music, with a history of 3,000 years, are kept alive thanks to the devotion of generations of musicians. Wu Wenguang (above), a virtuoso performer, has passed on his skills to his students, including Huang Mei and Sun Haopeng. (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

Family tradition

Wu, born in Changshu, Jiangsu province, learned to play the guqin with his father, Wu Jinglue (1907-87), who was also a guqin master and founded the guqin music school of the Wu family.

Wu Wenguang graduated from the China Conservatory of Music and the Chinese National Academy of Arts before he went to the United States to study musicology at Wesleyan University with a full scholarship from 1985 to 1990. Since returning to his home country, Wu Wenguang has been teaching at the China Conservatory of Music.

"My father, once a member of a guqin troupe in Shanghai, devoted his life to the instrument, which naturally influenced me. I am the second generation of my family keeping on the tradition of playing and promoting the instrument and my daughter is the third generation," says Wu Wenguang, adding that there are many different guqin schools in the country, which keep the ancient instrument alive.

One of the key factors of the revival of the instrument is tablature. According to Wu Wenguang, traditionally, guqin music is written in abbreviated characters that indicate how to use the hands and interact with the seven strings. This is unique compared to Western music. In guqin music, there's no obvious rhythmic indication, which is like poetry — we are given the words but there are no instructions on how fast or slow to read the poem.

The guqin and its music, with a history of 3,000 years, are kept alive thanks to the devotion of generations of musicians. Wu Wenguang, a virtuoso performer, has passed on his skills to his students, including Huang Mei (above) and Sun Haopeng. (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

The guqin and its music, with a history of 3,000 years, are kept alive thanks to the devotion of generations of musicians. Wu Wenguang, a virtuoso performer, has passed on his skills to his students, including Huang Mei (above) and Sun Haopeng. (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

"There are about 3,000 ancient songs in guqin's repertoire. Different performers can have different interpretations," says Wu Wenguang, who, along with his father, has re-created over 100 ancient scores. For example, they have recovered all of the scores collected in a guqin handbook, titled Shenqi Mipu ("marvelous secret music score"), which included 64 music pieces and was compiled by Zhu Quan — one of the sons of Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Besides ancient guqin songs, Wu Wenguang has also adapted contemporary music works into his performances, which has helped expand the repertoire.

Wu Ye, daughter of Wu Wenguang, is carrying on the family tradition of playing the instrument and is keen on composing new music for the instrument.

"Guqin playing was developed as an elite art form and now it has gained a popularity among young people with a new wave of interest in the nation's traditional culture and the government's efforts to promote this," she says.

Since 2020, she has initiated and organized a series of guqin concerts. With different themes, the concerts appealed to a young audience. The latest concert was held on May 20 in Beijing.

The guqin and its music, with a history of 3,000 years, are kept alive thanks to the devotion of generations of musicians. Wu Wenguang, a virtuoso performer, has passed on his skills to his students, including Huang Mei and Sun Haopeng (above). (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

The guqin and its music, with a history of 3,000 years, are kept alive thanks to the devotion of generations of musicians. Wu Wenguang, a virtuoso performer, has passed on his skills to his students, including Huang Mei and Sun Haopeng (above). (WANG JING / CHINA DAILY)

New inheritors

Huang Mei, one of Wu Wenguang's students, is one of the first musicians in the country to hold a PhD in guqin music.

"Wu (Wenguang) not only taught me how to play the instrument, but also how to comprehend the spirit behind it, especially what it symbolizes in traditional Chinese culture," says Huang, 44.

"I've noticed that many young people enjoy guqin nowadays. They find they can escape from their daily lives temporarily by playing or listening to guqin music, which makes them feel calm."

Sun Haopeng, 28, is a student of Huang and Wu Wenguang. "When I listened to the guqin for the first time, I was 14 years old. Back then, soccer was the most important part of my life and I dreamed about becoming a soccer player. The guqin gave me the feeling that I had never experienced before; I was quiet and focused."

Thanks to his uncle, who runs a guqin business, from manufacturing the instrument to teaching it, Sun learned to play and enrolled to study at the China Conservatory of Music in 2014. He practiced about eight hours a day.

In 2021, when Wu Wenguang had a concert marking the 65th anniversary of his music career, his students, including Huang and Sun, also performed.

Contact the writer at chennan@chinadaily.com.cn