Skill of transferring images onto paper is an art form steeped in history, Zhao Xu reports.

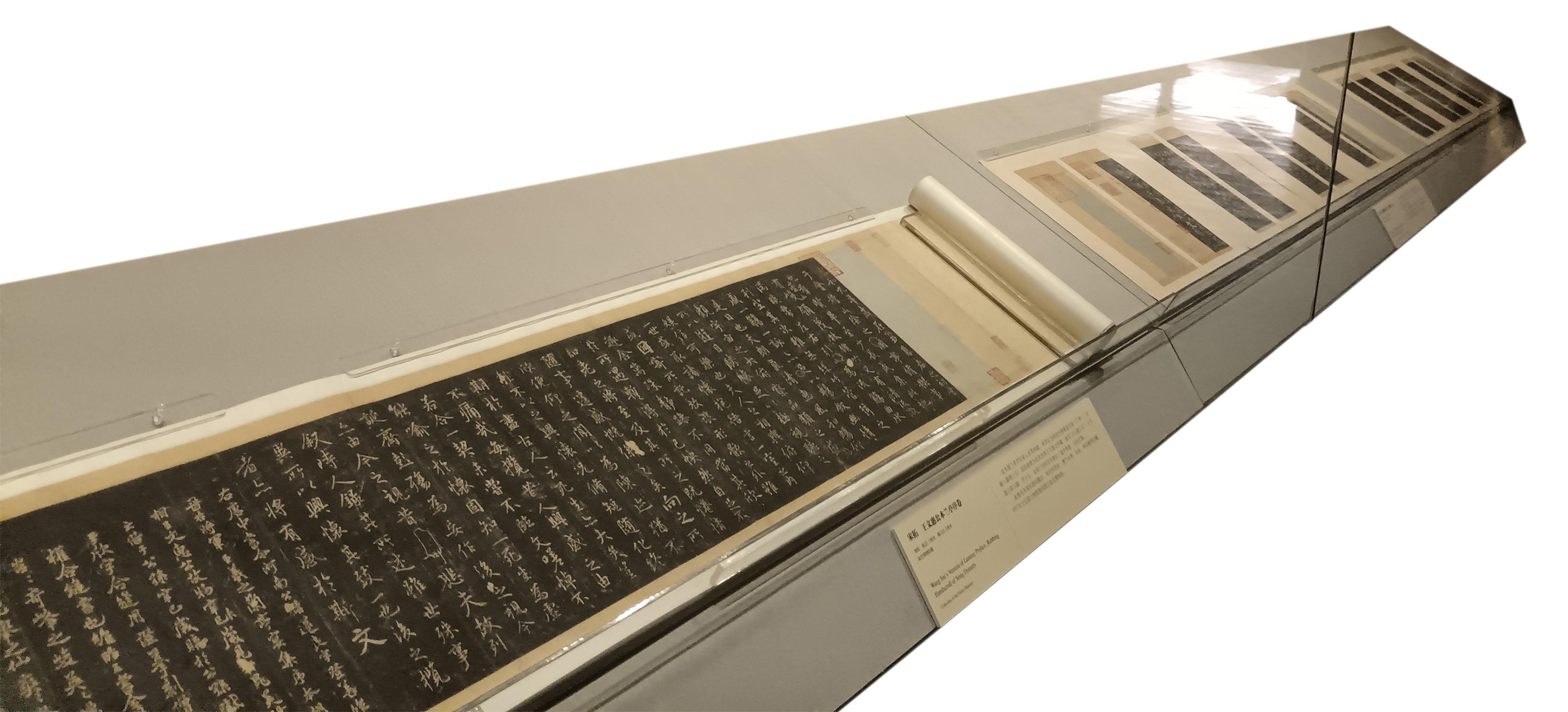

Rare Song Dynasty (960-1279) rubbings are now on display in an exhibition at Beijing's Palace Museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Rare Song Dynasty (960-1279) rubbings are now on display in an exhibition at Beijing's Palace Museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Rubbing, the tracing of characters onto a piece of paper, came into its own during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Woodblock printing had been invented two centuries earlier and even movable type printing using metal typefaces had appeared. Yet for those who were aiming not just for the content but the display of calligraphic art of a particular piece of writing, rubbing seemed the best option.

For any rubbing to take place, a particular piece of calligraphy must first be transcribed from paper to stone — or wood on rarer occasions — by a master engraver at a 1:1 ratio.

What we have here is not just a showcase of the beauty of ink and paper, the art of calligraphy, engraving and rubbing, but also the telling of stories steeped in cultural pride and communal spirit.

Wang Xudong, director of the Palace Museum

This was no easy task, but the ultimate goal was not to let the characters stay there, but instead, to transfer their vitality to the paper.

To do this, a thin piece of paper was placed over the surface of the stone tablet engraved with characters. Then water, and subsequently ink, was applied smoothly to the back of the paper with just the right amount of pressure, to soften the paper and allow for a thorough transfer of the details of the stone tablet onto it. The paper was left to dry and to eventually be lifted off the stone surface, carrying with it a reproduction of the original.

Repeated numerous times during the Song era, this manual technique enabled educated members of Song society to have access to master calligraphic works either from their own times or from previous eras to whose cultural influences they had willingly subjected themselves.

Oftentimes, the original calligraphy, or even its stone inscription, became lost over time, thus making the rubbings the only surviving proof of the masterworks that had once existed. In that sense, the Song rubbings, and those behind them, have helped to preserve a cultural legacy much valued then and now.

Now, art lovers have the chance to sample some of the most prominent fruits from this collective effort, at an exhibition held at Beijing's Palace Museum and dedicated entirely to the Song rubbings. Of the 40 pieces on display, 20 are drawn from the collection of the Palace Museum, which holds a total of 150 Song rubbings. The other half are from the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

A Song era rubbing of the Preface to the Collection of Poems of the Orchid Pavilion, which is believed to have been written by 4th-century calligrapher Wang Xizhi. (ZHAO XU / CHINA DAILY)

A Song era rubbing of the Preface to the Collection of Poems of the Orchid Pavilion, which is believed to have been written by 4th-century calligrapher Wang Xizhi. (ZHAO XU / CHINA DAILY)

Founded in 1971 with the support of the late HK philanthropist J. S.Lee (1915-2007), the museum aims to serve the university community and the island by collecting, preserving, researching and exhibiting artifacts from ancient and premodern China.

Addressing the exhibition's opening ceremony on Sept 15, Rocky S.Tuan, vice-chancellor and president of CUHK, said, "For 60 years, CUHK has consistently placed great importance on traditional Chinese culture and humanistic values. We have upheld the mission to combine tradition with modernity, and to bring together China and the West."

On loan for the first time, the rubbings from CUHK's collection had been donated to the university's Art Museum by J. S. Lee, whose son Chien Lee was in Beijing on Sept 15.

"Unlike his siblings, my father didn't go to study overseas. Instead, he spent his time at the Yenching University in Beijing, where he acquired an enduring passion for premodern Chinese art and made lifelong friends with people whom he later joined in his collecting efforts," said Chien Lee.

One of those friends was J. S. Lee's Yenching University alumnus and Hong Kong-based banker-collector J.M. Hu (1910-93), whose donations of porcelain and other ancient Chinese artifacts today fill an entire gallery at the Shanghai Museum.

In 1975, Hu donated a Song Dynasty rubbing of a second-century stone inscription titled The Stele of Huashan Temple to the Palace Museum. In the current exhibition, it was reunited with another Song rubbing of the same inscription, which, thanks to the late Lee, entered the CUHK Art Museum upon its founding in 1971.

"The stone itself was destroyed during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)," said Shi Anchang, a highly regarded expert in rubbings from ancient China. "Today, there are only four existing rubbings, including the two showcased here, an additional one from the Palace Museum dated to the early Ming era, and a last one, also from the Song era, that is held at the Calligraphy Museum in Tokyo."

In 1975, Shi's mentor Ma Ziyun (1903-86) traveled to receive the precious gift from Hu.

"What we have here is not just a showcase of the beauty of ink and paper, the art of calligraphy, engraving and rubbing, but also the telling of stories steeped in cultural pride and communal spirit," said Wang Xudong, director of the Palace Museum.

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn