Skiers and snowboarders ride down a slope at the Niseko Hanazono resort, operated by Nihon Harmony Resorts KK, in Kutchan, Hokkaido, Japan, on Feb 15, 2015. The ski and snowboard resort, majority owned by Pacific Century Group, is located1000 metres below the peak of Mount Niseko Annupuri in Hokkaido. (TOMOHIRO OHSUMI / BLOOMBERG)

Skiers and snowboarders ride down a slope at the Niseko Hanazono resort, operated by Nihon Harmony Resorts KK, in Kutchan, Hokkaido, Japan, on Feb 15, 2015. The ski and snowboard resort, majority owned by Pacific Century Group, is located1000 metres below the peak of Mount Niseko Annupuri in Hokkaido. (TOMOHIRO OHSUMI / BLOOMBERG)

Japan’s ski resorts are suffering through one of the worst snow seasons on record, disappointing locals and foreign tourists and jeopardizing the country’s budding reputation as an international ski destination.

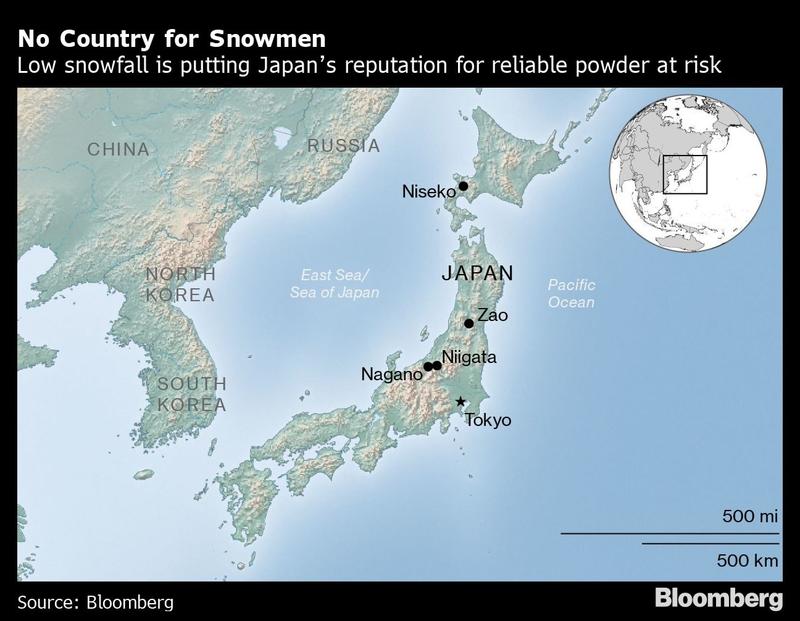

On the northern island of Hokkaido, where resorts like Niseko are known for reliable, fresh powder, the snow failed to fall in December and remains scant in the new year. In Sapporo, ski competitions have been canceled and the city is trucking in snow for its annual snow festival. December’s snowfall there was the lowest since the Japan Meteorological Agency began keeping records in 1961.

There’s still enough snow to ski at many resorts, but Japan’s built its international reputation on the reliability of its deep annual snowfalls

At resorts farther south, conditions are worse. In Nagano, site of the 1998 Winter Olympics, skiers dodge wide patches of grass on the slopes. In Zao, where Japanese kids usually squeal over ‘snow monsters’ created by sticky downfalls that cover trees, there are few to be found. Niigata, setting for the classic novel “Snow Country,’’ has had a quarter of its usual accumulation.

There’s still enough snow to ski at many resorts, but Japan’s built its international reputation on the reliability of its deep annual snowfalls. The Chinese New Year holiday, which starts later this month, will bring a massive influx of skiers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and China who may end up sorely disappointed. For a country concerned with tourism — and an industry already nervous about the effects of climate change — this winter is an ominous sign.

Andrew Lea, founder of the website Snow Japan, has lived in Niigata for 29 years, and by mid-January, he usually has at least a couple of meters of snow outside his house. This year, his garden was bare. “People who have been here 60 or 70 years can’t remember anything like this,” said Lea, whose site is an independent source for ski conditions at 500 resorts in the country, tracking daily snowfalls and accumulation. “Locals are getting a bit scared. If we don’t get snow soon, people are going to have to start closing down.”

Most of Japan’s ski resorts fall along the country’s west coast — from some of the peaks, skiers can see the Sea of Japan. The Japan Meteorological Agency, which tracks weather at hundreds of stations throughout the country, warned in early January that snowfall in the region was at its lowest in almost 60 years. At its station in Yuzawa, Niigata, the JMA measured snow depth at 8 cm as of Jan 16, compared with a 30-year annual average of 106. In Yamagata city, near Zao, it was 1 cm compared with an average of 20. In Hakuba, Nagano, the JMA recorded 0 cm compared with an average of 47 cm.

This winter has been unusually warm and dry, which meteorological researcher Hiroaki Kawase described as a consequence of “natural variability.” Still, he said, “Global warming turns snowfall to rain. So if this kind of winter happened 100 years ago” — when average temperatures were lower — “there’d be much more snow than there is now.” Without any mitigation, Kawase’s climate models predict Japan’s central mountains will get 10% to 20% less snow by mid-century due to climate change. By the end of the century, his models estimate a 20% to 40% drop.

It’s a global challenge. Climate change is already affecting snowfall in the European Alps, jeopardizing tourism in places like Austria and France. Many South Korean resorts are also short of snow this winter.

Japan’s ski industry took off in the boom years of the 1980s, and the number of active skiers and snowboarders grew to 18 million by 1998. But the country’s economic troubles and aging population took their toll. In 2016, the industry counted 5.8 million skiers (and snowboarders), fewer than in 1982.

Yet the facilities — and the snow — remained. More recently, the ski industry has become a pillar of Japan’s effort to attract more overseas tourists. Niseko in particular became an international destination because of its reliable snowfall. Australian powder hounds, worried about US travel after the Sept 11 attacks, led the way. Reports of more snow and fewer crowds spread, bringing skiers from the US, Canada, France and Germany.

In 2018, Snow Magazine named Niseko one of the top 10 ski resorts in the world, alongside Whistler, Telluride and Cortina D’Ampezzo. “Pow, pow and more pow,” the magazine declared, citing annual averages of more than 15 meters. “Take a snorkel.”

Skiers ride on lifts at the NISEKO Mt. RESORT Grand HIRAFU on Dec 5, 2019 in Niseko, Japan. (TOMOHIRO OHSUMI / GETTY IMAGES FOR TOKYU LAND CORPORATION)

Skiers ride on lifts at the NISEKO Mt. RESORT Grand HIRAFU on Dec 5, 2019 in Niseko, Japan. (TOMOHIRO OHSUMI / GETTY IMAGES FOR TOKYU LAND CORPORATION)

Not this year. In nearby Kutchan, JMA measured the snow depth at 67 cm as of Jan. 16, down 43% from its 30-year average. From hotels and restaurants to ski instructors and guides, businesses are feeling the impact of the snow shortage. Clayton Kernaghan, founder of Black Diamond Lodge and Hokkaido Backcountry Club in Niseko, usually begins running tours in the mountains around the resort on Jan 1. He had to call customers to cancel all trips this season through Jan 20. Unless there’s a huge snowfall soon, he’ll cancel everything through the end of the month.

ALSO READ: Mainland travelers remain keen on tours to Japan

“Our customers are not happy. It’s definitely hurting the business,” said Kernaghan, a 47-year-old Canadian who moved to Japan two decades ago. “If you build the business around the powder and then there’s no powder, it’s a disaster.”

Colin Hackworth has a different take on the situation. The president of Nihon Harmony Resorts, which operates Niseko Hanazomo, concedes this year’s snowfall is short of the typical season. But he points out that it’s just one year and Niseko still has plenty of snow for skiers. “It’s busy here,” he said by telephone, just after coming off the mountain. “We’re getting people from other resorts in Japan because they don’t have snow farther south.”

Hackworth, an Australian who ran resorts in his home country, was part of a group of investors who in 2004 acquired Hanazomo, one of four primary sections of Niseko. Three years later, Hong Kong billionaire Richard Li’s Pacific Century Group bought out Hackworth and his partners, but put him in charge of operations as the real estate conglomerate began to invest in improving the facilities. Today, there are new restaurants and lifts. A Park Hyatt hotel will open later this month.

Snow-making equipment wasn’t among the investments. Niseko, like more than two-thirds of Japan’s resorts, doesn’t make snow. They’ve never needed to. But with more winters like this one, Hackworth says, it’s not out of the question. “If this becomes a permanent condition, we would look at it,” he said. “We’d consider making snow.”

READ MORE: Tourists are swapping their Japan guide books for Instagram

Skiers will always hope for natural freshies, and the winter’s not over yet. On the morning of Jan. 17, Snow Japan reported 31 cm of new snow in Niseko and forecast more in the days ahead. Hackworth quickly relayed the news by text, attaching a photo for proof: “Snowing heavily in Niseko. Very heavily.”