A German national flag flies from a vessel near shipping cranes at the port of Hamburg in Hamburg, Germany, Feb 12, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

A German national flag flies from a vessel near shipping cranes at the port of Hamburg in Hamburg, Germany, Feb 12, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Just as Germany starts counting the cost of the coronavirus’s damage to economic growth, officials will get another glimpse of the shaky foundations it was built on.

Gross-domestic-product data this week will reflect not only how Europe’s biggest economy began a nose-dive in March, but also that its stalling engine was already in need of repair -- a legacy of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s rule that will probably outlast the outbreak.

Finance officials, whose budget package to combat the pandemic fallout is second only to the US, claim the space for stimulus now vindicates their reticence

While the virus-induced crash in activity may temporarily drown out any narrative of neglect, it might not silence observers who had long pushed for a large-scale budget stimulus to reinvigorate growth that was outpaced last year by all major euro-area peers, apart from Italy.

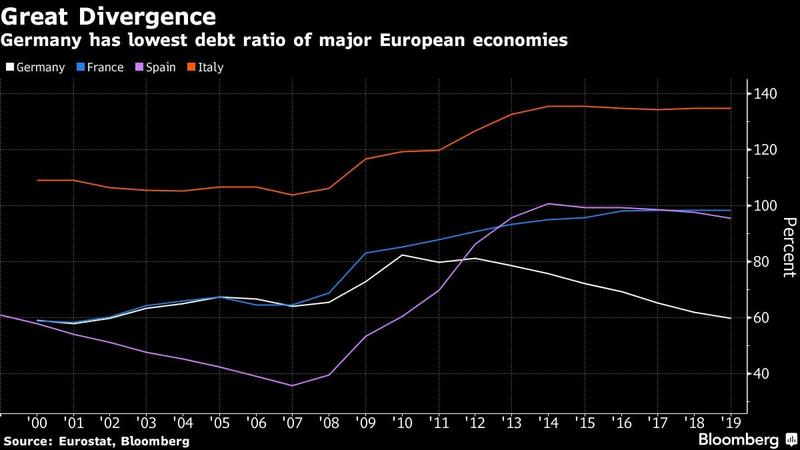

Spurred on by a debt-averse public, Merkel’s government zealously avoided such spending, even when it could borrow money for virtually nothing. Finance officials, whose budget package to combat the pandemic fallout is second only to the US, claim the space for stimulus now vindicates their reticence. But many economists say Germany could easily have afforded more spending beforehand.

READ MORE: Germany to ease lockdown as 1st phase of pandemic passes

“The fiscal consolidation over the last 10 years has not increased our ability to weather this crisis,” said Christian Odendahl, the Berlin-based chief economist at the Centre for European Reform. “We refrained from going on a massive spending spree or lowering taxes massively. For the health of the European and world economy, we probably should have done both.”

While lockdown measures to contain the virus only took effect in March, the damage for the whole first quarter will be eyewatering. Data on Friday may show the economy that is Europe’s motor shrank 2.3%, the most since the 2009 global financial crisis.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say

“We expect the economy to be less badly affected by containment measures imposed during lockdown than other countries. We forecast a contraction of 2.9% in 1Q and 9.3% in 2Q.”

Data on Friday may show the economy that is Europe’s motor shrank 2.3%, the most since the 2009 global financial crisis

The European Commission predicts a contraction of 6.5% this year, and while even that isn’t as bad as what Italy or Greece face, it’s enough to be Germany’s worst postwar slump. Tax revenue may drop significantly, an outlook Economy Minister Peter Altmaier might confirm on Thursday.

ALSO READ: Germany's infection rate dips below critical threshold

Officials have deployed hundreds of billions of euros in stimulus and aid, with measures ranging from furloughs for workers to loans and guarantees for businesses.

But growth was already in trouble, with Germany eking out the slowest expansion in six years in 2019, and many analysts reckoned stimulus was warranted well before the coronavirus. Its export-reliant model took a battering amid the US-China trade dispute, while the auto sector, reeling from the emissions-cheating scandal, struggled with a global shift to electric engines.

“Germany tends to suffer from global economic shocks, and that’s what we saw last year,” said ABN Amro’s Nick Kounis. “It seemed odd to everyone apart from German economic policy makers that there was this

underinvestment in Germany, given that they could finance so cheaply and that these investments would return more than the cost of the financing.”

That it was less odd in Germany was also because of local conditions. A constitutionally enshrined debt brake -- with an exception built in for crises -- and a habit of balanced budgets, supported by voters, meant any shift in stance would take time.

Germany eked out the slowest expansion in six years in 2019, and many analysts reckoned stimulus was warranted well before the coronavirus

Finance Minister Olaf Scholz began fiscal easing last year with incremental steps focused on green initiatives, but the government resisted pressure for a major stimulus.

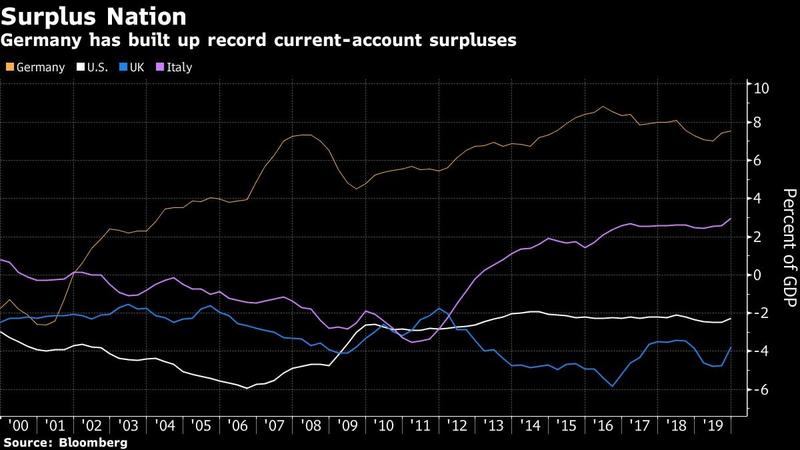

Leading those calls was the International Monetary Fund, which said the country needed investment and tax cuts to lower its current account surplus and aid its own economy. The European Central Bank also sought fiscal easing, while not citing Germany by name.

Germany has trailed Britain and France on information technology and infrastructure spending for years, according to the OECD. Its national railway service is notoriously unreliable, and the country is outranked by some neighbors on mobile phone connectivity.

Longtime domestic critics of Germany’s fiscal stance include Marcel Fratzscher of the DIW Institute in Berlin, a former ECB official who observes that the lack of outlays on aging capital stock such as buildings or roads means state investment has actually been negative for years. Municipalities last year cited a 138 billion euro (US$150 billion) spending shortfall, with schools, streets and administrative offices top of the list.

Restoring the economy might require more than just money, but rather a new vision from Merkel or a successor replacing her later next year

“If it creates more economic dynamics, it finances itself,” said Fratzscher. “Had they done more investment, Germany would have had exactly the same ability to react to the crisis as today.”

One caveat to that narrative was repeated in a recent report by Germany’s Council of Economic Experts, who noted that dilapidated buildings and roads aren’t the result of a lack of funding, but rather construction bottlenecks and bureaucracy. And the crisis has underscored Germany’s hospital provision to be world class.

Whatever the underlying challenges, they will need addressing soon if the country -- and even the wider region -- wants to avoid falling by the wayside of global growth. The all-important auto sector, for example, stands to lose 100,000 jobs as part of the shift toward lower emissions, according to labor union IG Metall.

Restoring the economy might require more than just money, but rather a new vision from Merkel or a successor replacing her later next year. In the meantime, the country can still take some comfort.

“Maybe higher investments would have made Germany more resilient, maybe it should have cut taxes, or become less dependent on foreign demand and cars,” said Christian Schulz, director of European research at Citigroup. “These are all valid arguments to be had. But fiscal space seems to be a luxury in this crisis.”