Monetary policy could be tighter than it looks as the pace of government borrowing eclipses the record stimulus of central banks.

The Federal Reserve’s massive asset-buying program hasn’t been matching the surge in US government debt issuance, Goldman Sachs Group Inc calculates. And it’s much the same with other nations, with only New Zealand set for a net decline in publicly held debt outstanding.

That suggests – low as they are – sovereign bond yields in developed economies are higher than they otherwise would be if central banks were buying more. If sustained, that’ll mean a growing proportion of bonds end up in private hands, rather than central bank or foreign official holdings, as governments continue to rack up their deficits.

“Central bank buying should absorb a substantial amount of upcoming issuance, though we expect increases in ‘free float’ across most markets, most notably in the US,” Goldman analyst Avisha Thakkar wrote in a note Thursday. That “adds to the medium-term case for higher yields and steeper curves,” she wrote.

Central banks do not have a lot of policy space left and are not moving quite as fast as we would like to add monetary accommodation.

Krishna Guha, Analyst, Evercore ISI

The current arrangement is a contrast with the quantitative easing that followed the financial crisis, when European Central Bank and Bank of Japan purchases far outstripped what their governments were then borrowing.

Though the Fed’s buying didn’t exceed Treasury issuance, the US bond market benefited from the largesse of others as European investors in particular were pushed out of their home market and loaded up across the Atlantic.

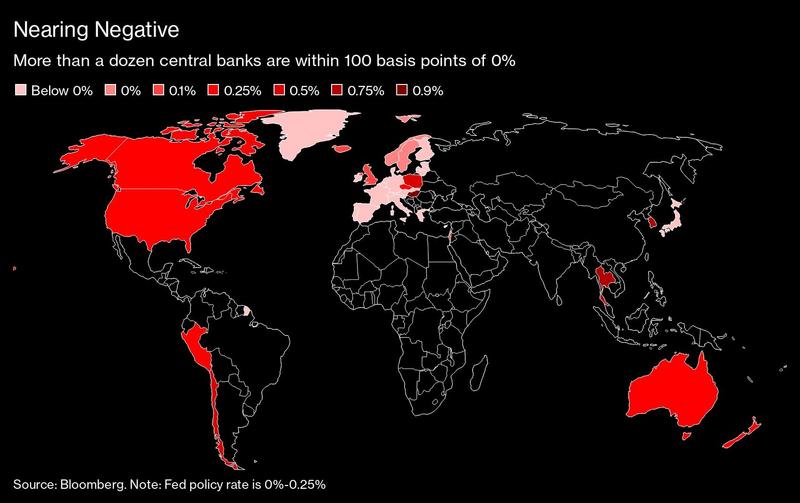

Nearing Negative

Some parts of the US money markets this month have suggested bets that the Fed will need to adopt a negative interest-rate policy, in the face of repeated doubts raised about that option by central bank Chairman Jerome Powell and other global peers.

While a variety of causes has been identified for the pricing, there are plenty of central bank watchers who see the likelihood of further action.

“Central banks do not have a lot of policy space left and are not moving quite as fast as we would like to add monetary accommodation,” Evercore ISI analysts including Krishna Guha wrote in a May 11 note. “We hope that June will see another wave of aggressive monetary policy action” in the US, euro region and UK, they wrote.

Calls for more coincide with forecasts suggesting a longer-term hit than the v-shaped recovery envisioned by many back in February. The coronavirus pandemic could cost the world economy as much as US$8.8 trillion, or almost 10 percent of global gross domestic product, depending on the outbreak’s length and the strength of government responses, according to the Asian Development Bank

Jerome Powell, chairman of the US Federal Reserve, speaks during a news conference in Washington, D.C., March 3, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Jerome Powell, chairman of the US Federal Reserve, speaks during a news conference in Washington, D.C., March 3, 2020. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Not everyone sees an inexorable ramp-up in central bank moves. Torsten Slok, chief economist at Deutsche Bank Securities, said monetary authorities will be looking for an exit from their current balance-sheet ramp up when conditions calm.

“Once the emergency situation is over the Fed and ECB would likely prefer to not be active in the long end of government bond markets because it blurs the line” between fiscal and monetary policy, he said.

Even so, others see the prospect of widespread adoption of the yield-curve control policies adopted by central banks in Japan and Australia – putting an explicit cap on yields, and therefore borrowing costs, as government deficits keep swelling.

“This appears to the same direction that other central banks are moving in,” rather than negative rates, Jane Foley, senior foreign-exchange strategist at Rabobank in London, wrote in a Thursday note.