In this April 20, 2020 file photo, a housing construction site stands idle in the Punggol area of Singapore. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

In this April 20, 2020 file photo, a housing construction site stands idle in the Punggol area of Singapore. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

With restaurants and malls bustling, pre-pandemic life is slowly returning for people in Singapore -- except for the more than 300,000 migrant workers who make up much of the city’s low-wage workforce.

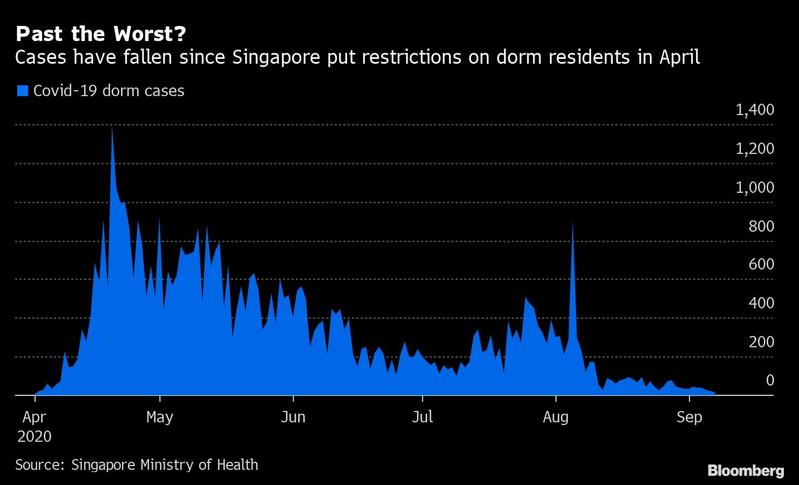

Since April, these workers have been confined to their residences with limited exceptions for work. After an extensive testing and quarantine campaign, the government cleared the dormitories where most of these workers live of COVID-19 in August, letting residents leave for several “essential errands,” like court appearances and doctor’s appointments.

Singapore has been saying it’s taking appropriate measures, considering that migrant workers have accounted for nearly 95 percent of the city’s coronavirus cases

The government said last month it was working toward relaxing more rules for workers. Those plans are now under threat, with new virus clusters emerging in the dorms, where workers from China, India, Indonesia and elsewhere share bunks and tight living spaces.

“Some days I feel very upset and can’t take it,” said Mohd Al Imran, a Bangladeshi worker with a local engineering firm. After months of confinement at the dorms, he got COVID-19 anyway. He was sent to a coronavirus care facility and said it was “very free” by comparison. “At the dorm you can’t go out from your room,” he said in a text message. “They treat it like a prison.”

Singapore has been saying it’s taking appropriate measures, considering that migrant workers have accounted for nearly 95 percent of the city’s coronavirus cases. But the resurgence, so soon after the dorms were declared COVID-free, is raising questions about whether Singapore’s conditions for its low-wage work force undermine the efforts to stamp it out.

“If you’ve got relatively socio-economically deprived people in crowded housing, you’ll get COVID-19 transmission at a higher rate,” said Peter Collignon, an infectious diseases physician and a professor at the Australian National University Medical School. It’s not inappropriate to treat higher-risk groups differently, he added, but “it’s unreasonable to put restrictions on people when there are things you can fix up.”

While experts say it’s reasonable to cordon off specific areas to quash an outbreak, they also say the conditions in the dorms are ripe for future transmission. The ventilation isn’t always good, and bathrooms are shared among a dozen or more. Government standards currently specify a minimum of 50 square-feet of personal space, roughly equivalent to a third of a parking spot -- conditions that “will always pose a risk of outbreaks,” said Raina Macintyre, a professor of global biosecurity at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

ALSO READ: Singapore's Lee identifies virus missteps, urges vigilance

ALSO READ: Singapore's Lee identifies virus missteps, urges vigilance

Poor and disenfranchised populations around the world have borne the brunt of the global pandemic, highlighting wide social and economic inequalities that existed long before COVID-19. In the best of times, Singapore’s migrant workers live with more restrictions than citizens and white-collar expats; with clusters rising again in the dorms, the prolonged lockdown-like conditions have brought new psychological stressors, along with renewed debate about the city-state’s deep reliance on this part of the workforce.

In local media and on Facebook, reports of self-harm and suicide attempts among migrant workers have circulated. When asked, Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower said these tend to be isolated incidents that reflect existing, underlying mental illness or trouble back home. Either way, social service groups say they’re swamped with calls for help from workers.

The situation “has definitely deteriorated in the last two months,” said Alex Au, vice president of the local migrant aid group, Transient Workers Count Too. “The tone of the conversations have changed a lot. There’s a lot of ‘I don’t care if you don’t even get me my salary, just get me out of here. I want to go home.’”

As of June, Singapore's government had moved more than 32,000 workers into temporary accommodations in response to the crisis

With overtime, a migrant worker could earn S$600 (US$438) to S$1,000 a month, far less than the monthly cost of a typical three-room apartment. The dorms still eat up a chunk: For around S$350, a worker can get a bunk bed in a room shared with 12 to 16 others.

The amenities vary. There are typically some kind of health services, like a clinic or a sick bay, as well as recreation spaces, mini-marts and indoor and outdoor seating areas.

As of June, the government had moved more than 32,000 workers into temporary accommodations in response to the crisis. Longer term, it plans to build 11 new dorms which will limit occupancy to 10 single beds per room; toilet, bathroom and sink facilities will be shared by every five residents, down from 15 currently.

Close quarters are ideal for the spread of a highly contagious virus like COVID-19. After officials instituted broad, city-wide restrictions in April, cases exploded in the dorms, eventually peaking at more than 1,000 a day. By May, with lockdown measures still in place, Singapore had one of the biggest outbreaks in the region.

The country responded with an aggressive testing strategy and, as case counts began to fall, began the process of reopening in mid-June. Dorm residents, though remain on virtual lockdown, with exceptions for those who had jobs to go to -- some, but not all, of the city’s construction projects were allowed to start up again.

ALSO READ: Construction delays as Asian cities struggle without migrant workers

The dorm exits are monitored, and before workers can go to work or run one of the sanctioned errands, their employer must notify the government’s Ministry of Manpower. This is a trade-off many residents are willing to make. Many are owed wages, and the health costs may be worse back home. Out of more than 57,000 reported cases in Singapore, only 27 patients have died.

Ah Hlaing, a Burmese worker at an elder-care center, has been riding out her quarantine in a Holiday Inn since May. “I do morning exercise, eat breakfast, watch the news, movies,” she said. “I’m on Facebook, eat lunch, have a bath, dinner, pray and sleep.”

Fewer people, though, have jobs to go to these days, cutting off the biggest allowable reason to leave the dorms. On an annualized basis, Singapore’s GDP dropped nearly 43 percent in the second quarter compared with the previous three months. Many construction projects are also on hold until employers can meet safe distancing and testing criteria.

So they’re largely confined to their compounds. “I don’t know until when I will be quarantined, and I don’t have any income,” said Bob Bu, a 33-year-old Chinese national who worked as a restaurant manager until he lost his job in a salary dispute with his employer. “I was under great mental pressure and couldn’t sleep for a while, because of the uncomfortable environment of the dormitory.”

At construction company Kori Holdings, Ltd., ten of the 200 migrant employees have told Chief Executive Officer Hooi Yu Koh that they’d like to go home.

READ MORE: Singapore sees slow recovery as economy plunges by record

“I could understand the concern of the workers in isolation, with family members worrying about their safety, being confined to the dormitories,” he said. “They just want to return home to their family as well as to ensure that the family knows they are safe.”

As outbreaks ebb and flow, the government has warned that the city-state won’t return to pre-COVID norms any time soon. Instead the leaders are describing a “new normal,” where crowds and large gatherings are restricted until there’s a vaccine and social distancing is enforced.

For Singapore’s migrant workers, that’s ushered in a series of safe living measures, including the mandatory use of a government contact-tracing app. Employers also have to ensure that dorm workers as well as those in sectors like construction go for routine testing every 14 days. In at least one dorm, residents have been allowed one 30-minute visit to the on-site amenities a day, otherwise they’re expected to be in their room or at work.

“This is not the ideal situation,” said Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious diseases physician at Singapore’s Mount Elizabeth Hospital. “But let’s look at the facts. There’s little to no transmission in the [broader] community. If you need the economy to move, would you release the community people or the dormitory workers? The safety of others overrides the interest of an individual.”