In this July 10, 2020 file photo, newly constructed residential apartment buildings stand in this aerial photograph taken above Gimpo, South Korea. (SEONGJOON CHO / BLOOMBERG)

In this July 10, 2020 file photo, newly constructed residential apartment buildings stand in this aerial photograph taken above Gimpo, South Korea. (SEONGJOON CHO / BLOOMBERG)

Jenny Lee has a dream: To own an apartment in Seoul, South Korea’s capital, where homes sell at around a US$1 million each.

In Korea, us 20-somethings only have two ways to get rich: Either we win the lottery or trade shares. We know we will never be rich on whatever wages we earn. We will never earn enough to buy a home.

Jenny Lee, day trader

The 27-year-old, who was jobless for a year until last month and rents a room at a dormitory near Seoul, will have her work cut out making that kind of money. She lacks a degree from a “good” college -- key to landing a coveted job at conglomerates like Samsung Electronics Co which dominate the economy, and she is a woman in a country where patriarchal norms have been hard to shake off. In the meantime, she thinks she’s struck on a solution: Day trading.

“In Korea, us 20-somethings only have two ways to get rich: Either we win the lottery or trade shares,” said Lee, whose new job is at a hospital, perhaps the only big employer in these COVID-19 times. “We know we will never be rich on whatever wages we earn. We will never earn enough to buy a home.”

In many ways, Lee, who is currently betting on US tech stocks, is part of the global surge in retail trading during the pandemic. Such investing has mushroomed in popularity in the US, as bored or fresh-out-of work people stay home amid lockdowns and take advantage of commission-free and easy-swipe apps like Robinhood and their stimulus money.

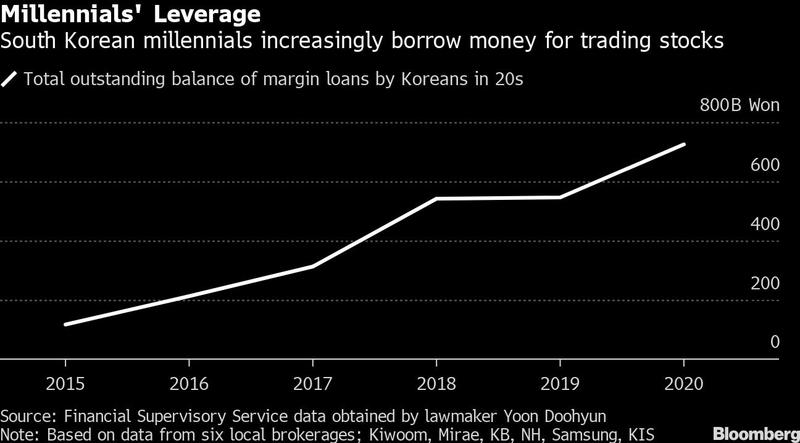

Lee is one of the millions of South Korean individual investors accounting for 65 percent of the trading value of the benchmark Kospi this year, up from 48 percent in 2019. The bulk of these fledgling investors are in their 20s and 30s, according to Korea Investment & Securities, a Seoul-based brokerage. And many of them take on debt: margin financing is up by 33 percent between December and June this year, data from the Financial Supervisory Service show.

What makes these punters unique, however, is that they’re hoping stock gains give them a way out of an economy where opportunities were dimming even before COVID-19 struck. The chaebol-driven export-led model of growth was already suffering from the stalling of globalization before the pandemic. Now, jobs are even harder to find and mortgages tougher to get.

ALSO READ: South Korea warns of ‘massive’ coronavirus risk

Many chaebols, like SK Group, are holding off hiring. Youth unemployment -- for those between 15 and 29 years old -- hit 10.1 percent in the second quarter, well above the 4.4 percent total. That may be lower than the almost 20 percent rate American youngsters currently face but South Korea is also a country where employees are hard to fire. Half of the record 682,000 people who gave up on looking for a job in August were in their 20s or 30s, Statistics Korea data show. Lee is currently studying for an exam that gets her an entree into the civil service. The pass rate of the exam is 40-to-one, while the salary is a mere US$1500 a month. Her starting wage, if she got into a chaebol, would be just around US$34,000 a year.

“Sociology” is a better indicator of what’s driving the stock market than economics, said Jeon Kyung-Dae, chief investment officer for equities at Macquarie Investment Management Korea. Low interest rates make matters worse, he said, eroding the value of savings every day.

“Korean millennials are desperate, confronting a frozen job market,” said Lee Han Koo, an economics professor at the University of Suwon, adding that rising real-estate prices are magnifying this sense of frustration. “In this environment, stock trading becomes a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” for riches.

The government, wary of a housing bubble, has weighed in to cool speculation, capping the loan-to-value levels for homes under 900 million won at 40 percent, for instance. Korean housing prices have climbed non-stop since 2014, and homes have become increasingly unaffordable. The median price of apartments in Seoul, where half of Koreans live and most companies are based, is 918.1 million won (US$792,800), compared with the country’s US$32,047 gross national income per capita. The nation’s household debt-to-disposal income of 180 percent is now the highest among OECD countries.

“It’s almost impossible for me to buy a house without help from my parents so I’m hoping that my stock trading gives me the profits to buy a home,” said Park Sung-woo, a 28-year-old employee at a recycling business company in Seoul.

South Korean individual investors are no strangers to speculation. They joined the global dot-com bubble and ensuing collapse in the late 1990s; latched onto exotic structured notes tied to stock and foreign currencies a decade ago; were enamored of bitcoin in 2017 and lost money on illiquid hedge funds last year. This time, however, everyone’s trading.

“I’ve had friends who piled into biotech stocks because they liked the name of the company,” said Jang Ho-yoon, a 26-year-old economics student who noted that all five of his family members are now trading stocks.

READ MORE: S. Korea retail investors charge into China tech stocks

If history is any guide, at some point regulators may try and tamp down on some of the speculation. The Kospi is up about 6 percent this year while tech-heavy Kosdaq has risen more than 25 percent, making them among the world’s best performing indices this year. But for now, Koreans see stock trading as the fastest route to homebuying.

“There used to be a few ladders for Koreans to climb to upgrade their social status -- you study hard, graduate from a good college, get a decent job at a chaebol, and then finally, buy a Seoul home,” said Dong-Hyun Ahn, an economics professor at Seoul National University.

“Now even if you have a good degree and a conglomerate job, it’s impossible to buy a home.”