A relative (right) consoles an Indian woman crying as she holds marigold garlands which are to be placed on the body of her husband who died of COVID-19, in Gauhati, India, Sept 28, 2020. (ANUPAM NATH / AP)

A relative (right) consoles an Indian woman crying as she holds marigold garlands which are to be placed on the body of her husband who died of COVID-19, in Gauhati, India, Sept 28, 2020. (ANUPAM NATH / AP)

GENEVA - The World Health Organization (WHO) said on Tuesday that one million deaths from COVID-19 was “a very sad milestone”, after many victims suffered “a terribly difficult and lonely death” and their families were unable to say goodbye.

The global coronavirus death toll rose past a million on Tuesday, a grim statistic in a pandemic that has devastated the global economy, overloaded health systems and changed the way people live.

“So many people have lost so many people and haven’t had the chance to say goodbye. Many people who died died alone... It’s a terribly difficult and lonely death,” WHO spokeswoman Margaret Harris told a UN briefing in Geneva. “The one positive thing about this virus is it is suppressible, it is not the flu.”

The global tally topped 33 million, according to the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. The worldwide caseload crossed 30 million on Thursday.

The US has by far the most recorded deaths, topping 200,000, with Brazil and India together accounting for over 200,000 more

The US has by far the most recorded deaths, topping 200,000, with Brazil and India together accounting for over 200,000 more.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called for solidarity to fight the pandemic.

"Our world has reached an agonizing milestone: the loss of 1 million lives from the COVID-19 pandemic," Guterres said in a video message. "It's a mind-numbing figure. Yet we must never lose sight of each and every individual life (lost)."

"We can overcome this challenge. But we must learn from the mistakes. Responsible leadership matters. Science matters. Cooperation matters. And misinformation kills," said Guterres.

ALSO READ: WHO warns of 1m more COVID-19 deaths

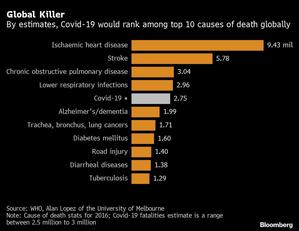

Actual fatalities from the worst outbreak in a century may be closer to 1.8 million -- a toll that could grow to as high as 3 million by the end of the year, according to Alan Lopez, a laureate professor and director of the University of Melbourne’s global burden of disease group.

The coronavirus’ rapid spread and ability to transmit in people who show no signs of the disease have enabled it to outrun measures to accurately quantify cases through widespread diagnostic testing.

“One million deaths has meaning by itself, but the question is whether it’s true,” Lopez said in an interview before the tally was reached. “It’s fair to say that the 1 million deaths, as shocking as it sounds, is probably an underestimate -- a significant underestimate.”

Even in countries with sophisticated health systems, mortality is difficult to accurately gauge. Tens of thousands of probable COVID-19 deaths in the US weren’t captured by official statistics between March and May, a study in July found, frustrating efforts to track and mitigate the pandemic’s progression.

The dearth of accurate data undermines the ability of governments to implement timely strategies and policies to protect public health and promote economic recovery. If the mortality from COVID-19 reaches 3 million as Lopez predicted, it would rank the disease among the world’s worst killers. An undercount in deaths could also give some people a false sense of security, and may allow governments to downplay the virus and overlook the pandemic’s burden.

An undercount in deaths could also give some people a false sense of security, and may allow governments to downplay the virus and overlook the pandemic’s burden

No system

India has confirmed more than 6 million COVID-19 cases, but accounts for only about 95,000 of the 1 million reported deaths worldwide, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University. The country, which has the highest number of infections after the US, lacks a reliable national vital statistics registration system to track deaths in real time. Meanwhile, in Indiana in the US researchers found that although nursing home residents weren’t routinely tested for the virus, they represented 55 percent of the state’s COVID-19 deaths.

“Yes, cases are reported daily everywhere, but as soon as you get to the next tier down, like how many were admitted to hospitals, there have just been huge gaps in the data,” said Christopher J. Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle. Medical data, including duration of illness and symptoms, help to ascribe a probable cause of death, he said.

READ MORE: COVID-19: WHO expects long-term response efforts

Patients with heart disease, diabetes, cancer and other chronic conditions are at greater risk of dying from COVID-19. Some governments, including Russia, are attributing the cause of deaths in some of these patients to the pre-existing condition, raising questions about the veracity of official mortality data.

WHO guidelines

In July, Russia recorded 5,922 fatalities due to COVID-19. At least 4,157 other deaths were linked to the coronavirus, but not included in the tally because of how the nation defines such deaths. Overall, it recorded 29,925 more deaths in July than in the same month of 2019.

The World Health Organization (WHO) laid out guidance for classifying coronavirus deaths in June, advising countries to count fatalities if patients had symptoms of the disease regardless of whether they were a confirmed case, and unless there was a clear alternative cause. A COVID-19 fatality should be counted as such even if pre-existing conditions exacerbated the disease, said the WHO. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released similar guidelines.

According to WHO guidelines, a COVID-19 fatality should be counted as such even if pre-existing conditions exacerbated the disease

Still, it may take health workers certifying deaths time to adopt the methodology, the University of Melbourne’s Lopez said. His research has received funding by Bloomberg Philanthropies, set up by Michael Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg News’ parent Bloomberg LP.

“Doctors often are learning as they go along, so they’re not certifying all the deaths that are due to COVID as COVID deaths,” Lopez said.

Japan drop

Although the pandemic has altered mortality patterns worldwide, not all of the changes are a direct result of the pandemic, he said. Physical distancing measures may have reduced road fatalities and deaths caused by influenza. In Japan, which has been scrutinized for its lack of widespread testing and relatively lax containment efforts, deaths fell by 3.5 percent in May from a year earlier even as COVID-19 cases peaked.

“The pandemic actually works in contradictory ways to affect mortality,” Lopez said.

Likewise, the economic cost of the pandemic -- which may top US$35.3 trillion through 2025 -- will be driven more by changes in people’s spending patterns than number of deaths and government-mandated “lockdown” measures, according to Warwick McKibbin, a professor of economics at the Australian National University and a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

“We estimate this outbreak is going to cost tens of trillions to the world economy,” McKibbin said in an interview. “The change in economic outcomes is caused by individuals changing their behavior, not because the government mandated a shutdown.”

READ MORE: WHO to provide 120m rapid virus tests to poorer countries

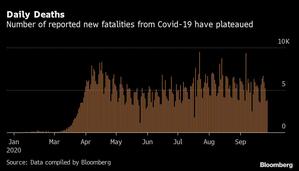

Worldwide, the growth in the number of daily deaths has eased since spiking in March and April, helped by improved medical care and ways to treat the disease. But as resurgences flare in Europe and North America ahead of winter and the flu season, COVID-19 fatalities may rise sharply again. It took nine days for cases in the UK to double to 3,050 in mid September, compared with the previous doubling time of five weeks, the BMJ journal said last week.

COVID-19 patients between ages 75 to 84 are 220 times more likely to die from the disease than 18-to-29-year-olds, according to the CDC. Seniors over 85 years have a 630 times higher risk of dying. The older age of fatal COVID-19 cases has made some people think “they’re old people, they’re going to die anyway,” said Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

“I have a really hard time with that,” Osterholm said in an interview. “That’s an unfortunate and very sad way to come to understand this pandemic. Many of those people who died are very important loved ones to so many of us that it’s hard to just dismiss it as it’s just a number.”