Storage tanks hold treated water at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, as seen on April 13. (KYODO NEWS VIA AP)

Storage tanks hold treated water at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, as seen on April 13. (KYODO NEWS VIA AP)

Japan’s decision to release more than 1 million metric tons of radioactive water from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant into the Pacific Ocean has sparked widespread criticism around the world.

The move threatens to have lasting consequences for communities and the environment, locally and much farther afield, said officials and experts, especially from China and Japan’s other neighbors within the region.

Kyodo News reported on April 13 that the release will start after two years. The contaminated water will first be diluted so that concentration levels of radioactive tritium, which can cause cancer, and other hazardous elements conform to national standards in Japan.

A spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry issued a written statement the same day, expressing the country’s “serious concern as Japan’s close neighbor and a stakeholder”.

Beijing asked Tokyo to reexamine the disposal of wastewater from the Fukushima plant, stating that it should not be discharged into the sea without adequate consultation and agreement being reached with all interested countries and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

The spokesman said that China would continue to closely follow the situation with the international community and reserves the right to make further responses.

Beijing pointed out that Tokyo made the decision without exhausting all possible means for safe disposal of the water, and had ignored doubts and opposition in Japan and overseas. Also, Japan failed to engage in adequate consultations with neighboring countries and the international community.

“This is extremely irresponsible and will seriously damage international public health and safety and the vital interests of the people of neighboring countries,” the Chinese spokesman said.

A protest outside the prime minister’s office in Tokyo on April 13 against the Japanese government’s plan to release contaminated water from the stricken Fukushima nuclear plant into the sea. (DU XIAOYI / XINHUA)

A protest outside the prime minister’s office in Tokyo on April 13 against the Japanese government’s plan to release contaminated water from the stricken Fukushima nuclear plant into the sea. (DU XIAOYI / XINHUA)

South Korea’s Foreign Ministry summoned Japan’s top envoy to Seoul on April 13 after Tokyo announced its decision.

Second Vice-Foreign Minister Choi Jong-moon met with Japanese Ambassador Koichi Aiboshi.

Koo Yoon-cheol, head of South Korea’s Office for Government Policy Coordination, said at a media briefing, “This decision from the Japanese government is outright unacceptable.

“The National Assembly, civic groups, local government and councils are all against the decision, and fisheries workers, experts and public opinion within Japan have also been against the move.”

However, the United States expressed support for Japan’s decision.

“Japan … has been transparent about its decision, and appears to have adopted an approach in accordance with globally accepted nuclear safety standards,” the State Department said in a statement on its website.

Ken Buesseler, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the US, said independent studies should be established for “seawater, seafloor and marine biota (all types of life in the sea), and not just for tritium, but for all of the radionuclides currently in tanks at the site.

“Given the strong currents such as the Kuroshio off Japan, any radioactive contaminants released from Fukushima Daiichi that are soluble would move largely across the Pacific to the east and not impact the coast of China, reaching the North American west coast in one to two years,” he said.

Bresseler added that insufficient information has been provided about the different radionuclides, other than that tritium is in each tank.

“Radioactive carbon is only one form of radioactive contamination in the tanks that could be released. Radioactive forms of strontium, ruthenium and cobalt are also present according to TEPCO’s (plant operator Tokyo Electric Power) website. Independent analyses of the tanks are needed.

“The non-tritium forms of radioactivity have greater health impacts and are more likely to end up associated with seafloor sediments and marine biota, such as fish. So a release plan that only considers tritium is not able to be fully evaluated.”

Activists demonstrate outside the Japanese embassy in Seoul, South Korea, against Tokyo’s decision. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Activists demonstrate outside the Japanese embassy in Seoul, South Korea, against Tokyo’s decision. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Jin Yongming, professor of maritime laws at Ocean University of China, said the dilution and discharge process must be subject to international supervision, as the ocean belongs to the world.

He said that as a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Japan has the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment, and to submit all relevant information to other countries.

Buesseler said what is most worrying is that nothing is known about the contents of each tank. Also, the cleanup has not been witnessed to the extent required for release to be considered.

“My concern is largely not about tritium, but the other forms of radioactivity that are of greater health concern — those more likely to be associated with seafloor sediments — hence they would not move with ocean currents and would accumulate on the seafloor near Japan. These non-tritium radionuclides are more likely to enter the marine food chain, so there is a greater concern with fisheries,” he said.

“While we have been told that these other contaminants can be, and will be removed, they need to take this step first and then show, with independent monitoring, the whole range of radioactive contaminants in each tank.”

Hiroshi Kishi, head of Japan’s federation of fisheries cooperatives, said he and his organization are “absolutely against” the water being released into the ocean, adding that the government’s decision is not supported by the Japanese public.

“It is inevitable that there will be reputational damage, regardless of how the water is disposed of, whether into the sea or into the air,” Kishi said.

“I want the government to clarify how it intends to respond to such reputational damage.”

Residents in Fukushima, most of the municipal assemblies in the prefecture and Japanese society are also opposed to the release.

A China Daily investigation found that 41 of Fukushima prefecture’s 59 municipal councils are against the plan, with 25 of them strongly opposed to it and 16 asking the government to “respond cautiously”.

On April 11, people from throughout the prefecture held a rally in Iwaki to protest against the plan, with members of environmental organizations and representatives from all walks of life expressing their anger and disappointment.

They used a slogan that called for the protection of Fukushima, fisheries and children.

A file photo of the Unit 4 reactor building at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station taken in November 2011. (DAVID GUTTENFELDER / AP)

A file photo of the Unit 4 reactor building at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station taken in November 2011. (DAVID GUTTENFELDER / AP)

A fisherman who wanted to be known only as Eguchi said, “We know that handling this water is a pressing problem, but if it is released into the ocean, all the efforts we fishermen have made to recover from the Fukushima disaster will be meaningless.”

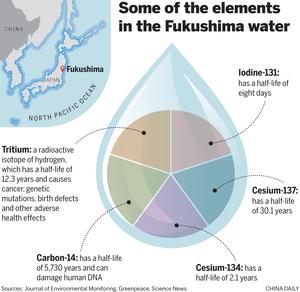

In 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake and a tsunami damaged the Fukushima plant’s cooling systems, causing three reactor cores to melt. Since the accident, thousands of tons of seawater have been pumped into the reactors as coolant. Groundwater that flowed into the damaged structures has become contaminated with radioactive nuclides.

TEPCO has stored more than 1 million tons of this water in the tanks at the site, but has said it will run out of storage space by autumn next year.

According to the Japanese government, releasing the contaminated water into the Pacific is the only viable option. The water will be treated with an advanced liquid-processing system, or ALPS, to remove most contaminants.

However, this process cannot remove tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, the lightest element.

Japan insists that dumping tritium-laced water into the sea is a common practice at nuclear reactors around the world, but many observers remain unconvinced.

Erbiao Dai, vice-president of the Asian Growth Research Institute in Fukuoka, said: “Japan and TEPCO have used a series of claims to support their plan. These include: the lack of further storage space for the water by 2022; that the water is not contaminated, as radioactive tritium is the only radionuclide it contains and this is harmless; and that there are no alternatives to discharging the water into the ocean. However, none of these statements are true.”

Dai said it is possible to include additional storage space for the water beyond next year, both on and off the Fukushima site, but the Japanese government has ruled this option out, stating that it would take “a substantial amount of coordination and time”.

“Meanwhile, long-term storage and processing of the contaminated water is logistically possible because tritium has a short half-life of 12.3 years, so delaying the start of discharges would allow the tritium to diminish naturally, which is a better way to safeguard people’s health and the environment,” Dai added.

The half-life of a reaction is the amount of time needed for a reactant concentration to decrease by half. Its application is used in chemistry and medicine to predict the concentration of a substance over time.

Dai added, “The ALPS the Japanese government is relying on is flawed. The companies that operate it, Toshiba and Hitachi General Nuclear Electric, have practically no experience in water processing.”

The effectiveness of the ALPS has been questioned. In 2018, experts found a large number of radioactive substances other than tritium, such as carbon-14, cobalt-60 and strontium-90, remained in treated wastewater stored the previous year.

TEPCO also acknowledged in August, for the first time, the presence of high levels of carbon-14 in the contaminated tank water. Dai said if the water is discharged into the Pacific, all the carbon-14 would be released into the environment.

“Once introduced into the environment, carbon-14 will be delivered to local, regional and global populations for many generations. Releasing the contaminated water into the ocean is clearly not based on science and engineering, but on the political interest of the Japanese government and the future viability of TEPCO,” Dai said.

Asked whether fish would have radioactive contamination, Buesseler, from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, said, “The question is not whether there is radioactivity in fish — yes there is in all fish — but how much more radioactivity has Fukushima added and how much more would be added with the proposed release of tank waters.”

Ma Jun, director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs in Beijing, said the Japanese government should release more information on the radioactive water and consult stakeholders before deciding on how to dispose of it.

Liu Xinhua, chief expert at the Ministry of Ecology and Environment’s Nuclear and Radiation Safety Center, told Science and Technology Daily, “The release of the large amount of wastewater from Fukushima will unavoidably result in radionuclide enrichment in sediments and marine organisms in locations near the release point.

“Some of the radionuclide could disseminate with the current, eventually affecting countries neighboring Japan, including China and North Pacific nations.”

There is no precedent for the disposal of a large amount of wastewater generated as the result of a nuclear accident, he said, adding that discharging it into the ocean is just one of five solutions the Japanese government has considered.

Liu said releasing the water into the sea is obviously the easiest option, as the other solutions are more costly, require advanced technology and take longer.

“The Japanese side needs to make public the evaluation results of the release plan … The decision should be made based on full consultation with neighboring countries,” he said.

The equipment TEPCO uses cannot remove tritium, which has a half-life of about 12.5 years, he said.

While the concentration of tritium in the wastewater is generally higher than the limit for release stipulated in Japanese laws and regulations, the density of at least two of the other six types of radionuclide in wastewater in some of the storage tanks also exceeds the limit.

Zhou Jinfeng, secretary-general of the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation, said once the radionuclide enters the ocean, it will be difficult to follow and monitor, and its negative impact on marine biodiversity and sea farming cannot be predicted.

“Although it is time- and labor-saving, releasing the wastewater into the ocean is a very irresponsible act by the Japanese government. Japan should organize scientists from stakeholder states for research and discussion. The impacts on the environment and ecosystems should be fully evaluated to seek the best solutions,” he said.

Zhou Yongsheng, professor and deputy director of the Japanese Studies Center at China Foreign Affairs University, said Japan’s decision is a “tricky” one, as it will wait for two years to discharge the water, by which time opposition “could be greatly reduced”.

Zhang Yunbi contributed to this story.

Contact the writers at wangxu@chinadaily.com.cn