This undated photo shows US pilot Lt Donald Kerr with his saviors at the East River Coloumn headquarter in Tuyang, Guangdong province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

This undated photo shows US pilot Lt Donald Kerr with his saviors at the East River Coloumn headquarter in Tuyang, Guangdong province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

HONG KONG - An American fighter pilot was downed in the territory of enemy control. A boy hid him in a foxhole and found local guerrillas for help. On a dark night, they decided to break the blockade by 1,000 enemy soldiers.

The episode, which sounds like some fictional story, was actually the true experience of "Flying Tiger" Lieutenant Donald W Kerr in Hong Kong during World War II.

Hong Kong, then a British colony, fell into the hands of Japanese invaders, about 80 years ago.

On Feb 11, 1944, Kerr's plane, flying in formation with 19 other P-40 fighters and twelve B-25 bombers, was on a mission to bomb Kai Tak airport located on the coast of Hong Kong's Kowloon, which had been turned into a Japanese airbase.

After shooting down one Japanese Zero fighter, Kerr's aircraft was hit and caught fire in a dogfight with three Zeros. He had to eject from the burning cockpit.

"Jeez, I'm going to land in a company of Jap soldiers - very convenient for them. Some little white buildings - their barracks, I suppose," Kerr said in a memoir he wrote when still in hiding in Hong Kong.

Fortunately, Kerr parachuted into hills to the north of the heavily-guarded airport and was found by Li Shi, a 14-year-old liaison boy of the Dongjiang (East River) Column, a guerrilla force led by the Communist Party of China.

In his journal, Kerr, not knowing Li's name as they did not understand the language of each other, called Li "Small Boy." "He was to have a leading part in my forthcoming travels. Though of course I didn't know it just then," Kerr said.

Li helped the injured pilot elude the first round of the hunt by Japanese soldiers and reported the situation to guerrillas, who then protected Kerr for days around the clock and successfully transferred him to safety under the nose of the enemy.

In the pointee-talkee of US pilots, words that ask guerrillas for help were printed in both Chinese and English: "I am an American airman helping China in its war of resistance and have been forced down here" and "how many li (500 m) away are the nearest Chinese guerrillas," among others.

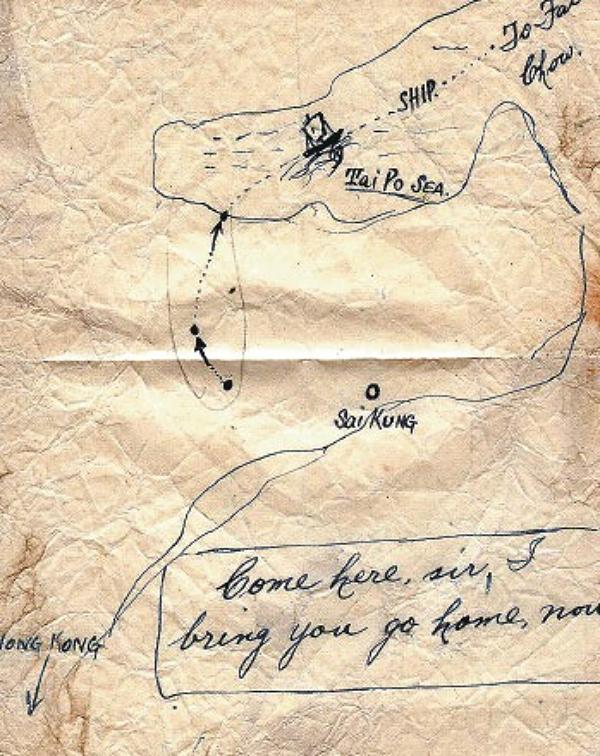

The note given to Donald Kerr by Chinese guerillas, which shows a hand-drawn map with a line of English words written at the bottom: "Come here, sir, I bring you go home now!" (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The note given to Donald Kerr by Chinese guerillas, which shows a hand-drawn map with a line of English words written at the bottom: "Come here, sir, I bring you go home now!" (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Accompanied by guerrilla fighters, Kerr arrived in early March at the headquarter of Dongjiang Column in what is now Shenzhen, a neighboring city of Hong Kong, and then safely returned to his home base in Guilin, south China's Guangxi, on March 29, said Wan So-ming, chairperson of the East River Column History Research Association.

The rescue of Kerr was no easy job. At the height of the search for him, the Japanese army deployed over 1,000 soldiers, as well as ships and planes.

"For some days after my airplane had been set afire by enemy bullets and I had descended to the ground by parachute, I looked upon my situation as nearly hopeless, but after I got under your care and as time safely passes I grew to feel most secure..." Kerr said in a thanksgiving letter to guerrillas in March.

Kerr was not the only pilot rescued out of Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation.

this undated photo shows US pilots and a P-40 fighter plane bearing the shark-face logo of the Flying Tigers. The aircraft was the same type that Donald Kerr flew to bomb a Japanese air base in Hong Kong in 1944. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

this undated photo shows US pilots and a P-40 fighter plane bearing the shark-face logo of the Flying Tigers. The aircraft was the same type that Donald Kerr flew to bomb a Japanese air base in Hong Kong in 1944. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

"My father told me they saved...(at least) eight American pilots and brought them to safety (from January 1944 to August 1945)," Wan said. Her father, Lin Ping, served as one of the leaders of the guerrilla force in Guangdong and Hong Kong.

During World War II, the Dongjiang Column rescued at least 89 foreigners out of enemy control, including British officers and soldiers, and also provided the US military with intelligence information on airports and docks in Hong Kong and the defense of the Japanese troops.

Kerr died in 1977. Years later, the manuscripts and some hand-drawn cartoons of the memoir were found by his sons. The journal was published in Hong Kong in 2015.

"Most American soldiers did not speak about the war after they came home. My father was the same - he only told the story of his rescue one time to my brother and me. Fortunately he wrote this journal that tells the story for everyone," David Kerr, the younger son of the late US pilot, said in the preface of the book.

In this undated photo, David C Kerr (left), son of Flying Tigers pilot Donald W Kerr, poses with descendants of Chinese World War II veterans during a documentary and book launch in Beijing. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

In this undated photo, David C Kerr (left), son of Flying Tigers pilot Donald W Kerr, poses with descendants of Chinese World War II veterans during a documentary and book launch in Beijing. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

His two sons Andrew Kerr and David Kerr have made multiple visits to China along with their families since 2008, tracing the escape routes of their father and meeting the guerrilla fighters of the Dongjiang Column, in particular Li Shi.

"The Kerr family greatly appreciates the unselfish help and cooperation shown to Lt Kerr in 1944," David Kerr said.

"We wish we could thank the old soldiers and villagers personally but most of them have died. So we must extend our thanks by keeping their memories alive in their children, grandchildren, and all the people of China."