Documentary series tells story of city's liberation in 1949

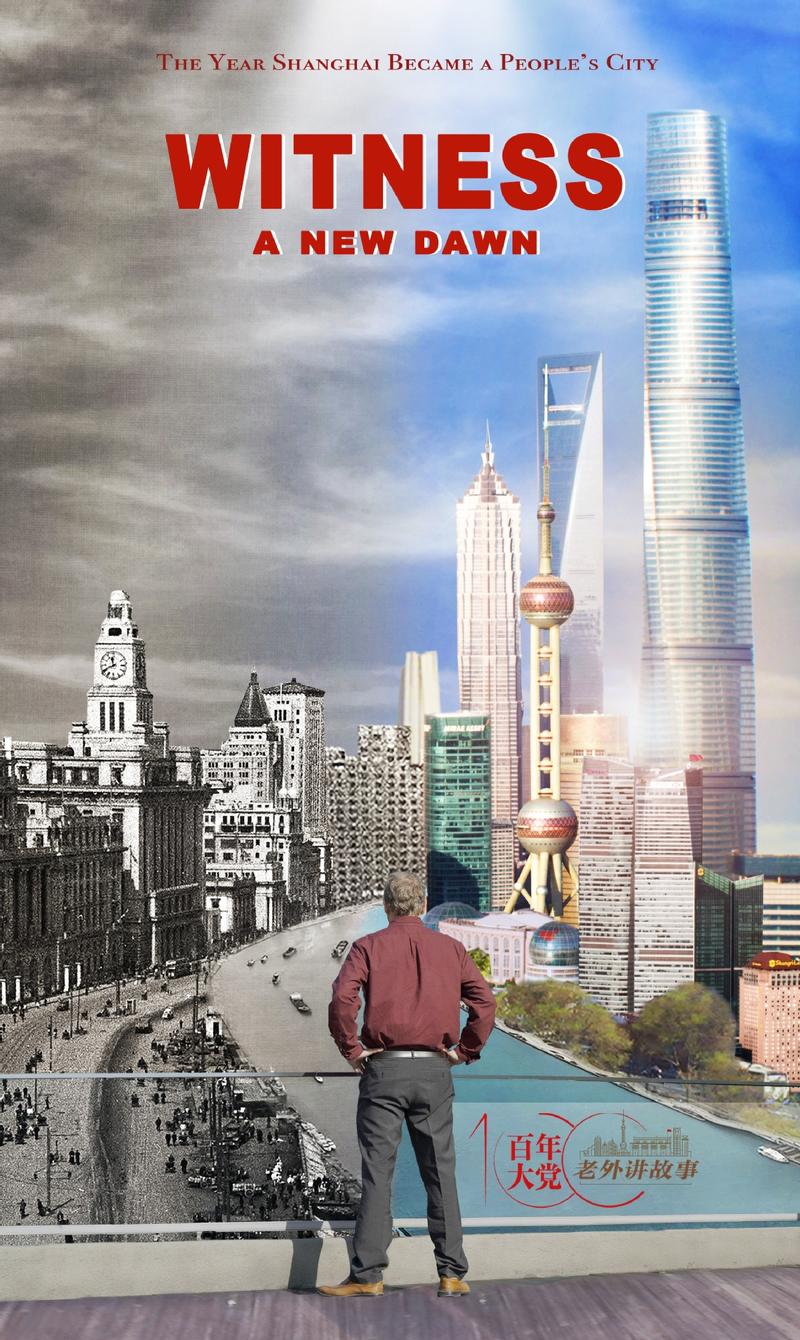

A poster for the Shanghai Media Group's documentary series. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A poster for the Shanghai Media Group's documentary series. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Just before People's Liberation Army troops battled forces of the Nationalists, or Kuomintang, for control of Shanghai 72 years ago, Bill Powell, editor of the English-language magazine China Weekly Review, wrote an editorial.

Part of it read, "We welcome the change that has come about and hope that the arrival of the People's Liberation Army will mark the beginning of a new era-an era in which the people of China can now begin to enjoy the benefits of good government."

Days later, Shanghai was liberated on May 27, 1949, when the Communists won the battle and took control of the city from the Kuomintang forces. Shanghai became the largest Communist-run city in the world at the time and made international headlines.

Wang Xiangtao, who filmed the documentary series Witness a New Dawn, which looks back at that period from the perspectives of foreign journalists and Western residents, said, "This important part of Shanghai's history was recorded by many foreign journalists who were still working and living in the city."

When Shanghai was forced to open to major foreign powers as a trading port after the Opium Wars in the mid-19th century-becoming a semi-feudal and semi-colonial city for about 100 years-thousands of foreigners were attracted to the metropolis. Major news agencies also sent journalists to work in the city.

Wang said: "All the material I used for the project came from Westerners writing in English. I hoped to present the story of Shanghai's liberation from their perspective and to let more people know about this chapter of history."

The front page of The Evening Democrat, a newspaper in Fort Madison, Iowa, United States, covers the withdrawal of the US Navy from Shanghai on April 25, 1949. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The front page of The Evening Democrat, a newspaper in Fort Madison, Iowa, United States, covers the withdrawal of the US Navy from Shanghai on April 25, 1949. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The documentary features the stories of expatriates in Shanghai, including diplomats, journalists, doctors and traders. They tell how the CPC won public support because of the discipline of the army, dedication to public welfare, and effective management, as the Kuomintang regime descended into chaos, plagued by corruption and inflation.

Wang, a filmmaker at the Shanghai Media Group's documentary center, spent several years browsing library records.

He also published a book last year titled Shanghai Liberated, compiling information collected from historical papers, personal accounts, correspondents and the memoirs of expatriates living in Shanghai.

Wang then set out to transform the information he had gathered into a motion picture. He visited United States academic Andrew Field, Adjunct Professor of Chinese history at Duke Kunshan University, who studied Asian history and was a "proud long-term resident of Shanghai for around 20 years".

With Wang directing and Field hosting the documentary, the duo filmed in many locations where significant events unfolded in 1949.

Field said: "At that time, foreign news agencies continued filing dispatches overseas and English-language newspapers continued to operate in the city. So, what did they have to say about the Communists? I thought it would be a very interesting story to tell, and it was.

"It is interesting to read those (positive) reports written 72 years ago, especially since the news media tends to focus on the bad. The new authorities secured a good world press, and by their actions surmounted any prejudice which might have formerly existed."

Shanghai residents read newspaper reports about the city's liberation. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Shanghai residents read newspaper reports about the city's liberation. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Amethyst Incident

In the series, Wang and colleagues visit landmark sites, including the top of Shanghai Mansion, known at the time as Broadway Mansion, the General Post Office Building on Suzhou Creek, and the Yangshupu Power Plant on the northern stretch of the Bund.

There is footage of Shanghai's urban landscape, with restored buildings, new high-rises and repurposed industrial heritage. As the story unfolds, it reveals a pre-1949 city plagued by a dysfunctional government, widespread corruption and inflation.

One episode features the Amethyst Incident, a significant event in Shanghai's history.

In April, 1949, the British warship HMS Amethyst departed from Holt's Wharf in Shanghai, which was owned by the British, and sailed along the Yangtze River to Nanjing, the Kuomintang government's capital, despite repeated warnings from the People's Liberation Army, which was about to cross the Yangtze.

The vessel's crew paid little heed to the warnings, as British forces had sailed freely on the river for more than a century.

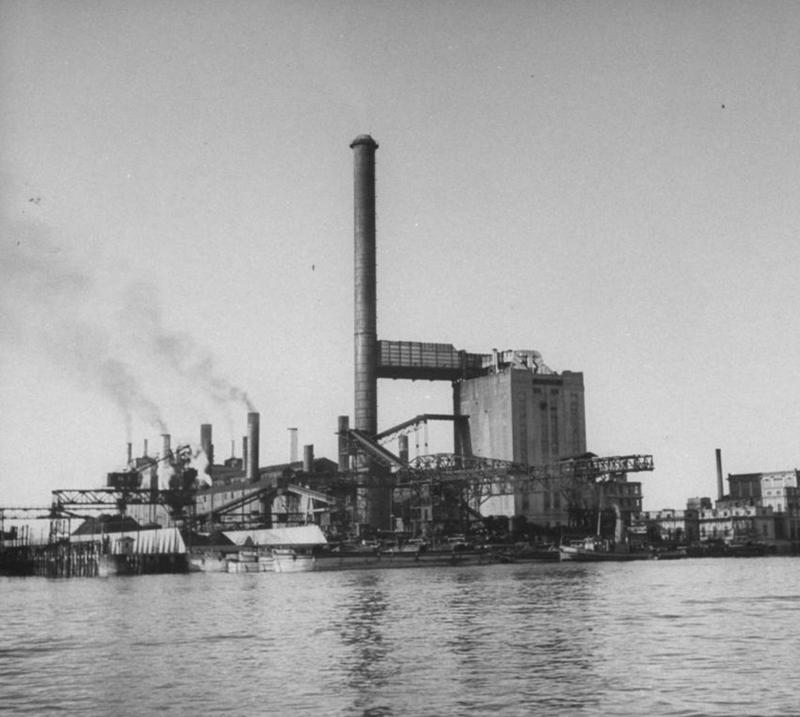

The Yangshupu Power Plant in Shanghai used to be a city landmark. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Yangshupu Power Plant in Shanghai used to be a city landmark. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Amethyst was hit by PLA fire, running aground and raising a white flag of surrender. The British were quick to send two bigger ships to the rescue, but both were driven out of the Yangtze by the PLA and experienced a total of 27 casualties.

The documentary features a page from the notebook of Life Magazine journalist Roy Rowan, on which he writes, "The crowds of stunned British and American spectators looked as shell-shocked as the severely wounded sailors being carried ashore. No less stunned, Shanghai's city officials, who realized that the Communists had done something no Chinese army ever dare do before-blow the warships of a Western power out of one of its rivers."

The Chicago Tribune reported that Shanghai's Chinese residents greeted news of the PLA attack on the British warship with delight, because the foreigners "who had kicked China around for 100 years were now getting what they deserved".

This view was voiced by John Leighton Stuart, the then-US ambassador to China, who said: "I could sense an undertone of national pride among other Chinese in this achievement. Commercial and naval ships of foreign countries, principally British, had long sailed up and down this mighty river at their own unbridled will, but now at last they had been bravely challenged and routed."

A few days after the Amethyst Incident, all foreign warships sailed out of the Huangpu River in Shanghai, since when such vessels have been not allowed to enter the riverway uninvited.

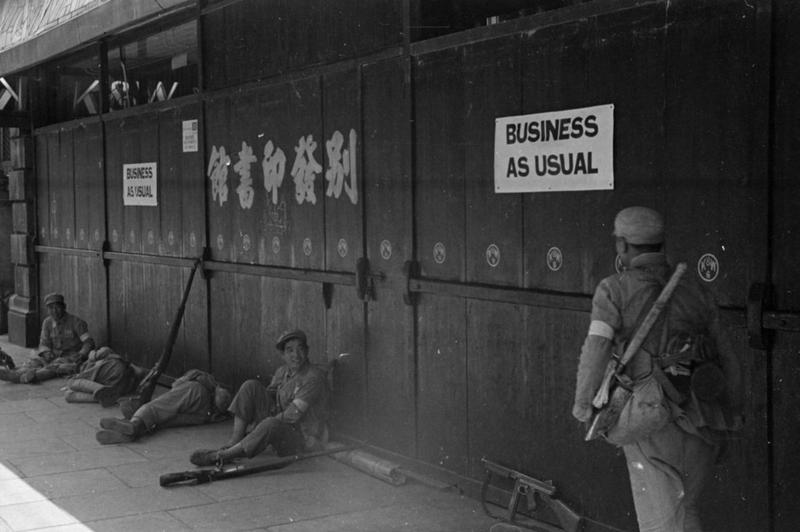

PLA soldiers take a break on the sidewalks. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

PLA soldiers take a break on the sidewalks. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Three-day battle

In the documentary, Wang states, "What impressed me most was how during the battle for the liberation of Shanghai, the PLA was instructed to cause as little harm and damage to the city and people as possible, and how the soldiers were so disciplined."

As the PLA advanced into downtown Shanghai in May, 1949, Suzhou Creek, which runs through the city, and large buildings along its banks became the last line of defense for Kuomintang troops.

Powell, the China Weekly Review editor, lived in Embankment Building overlooking the Suzhou Creek battlefield. At the time, this big apartment block housed more than 1,000 residents, 300 of them expatriates.

Ahead of the battle, the building became a refuge for the Kuomintang, who planned to make Shanghai a "Stalingrad of the East". Powell became anxious and scared, like others in the neighborhood.

He wondered if the PLA would lose patience and bring out its artillery to attack the river bank.

Another US journalist, Harrison Forman, was on the roof of the Cathay Hotel looking down on advancing PLA soldiers. What he saw surprised him.

North-China Daily News, an English-language newspaper in Shanghai, covers events in the city in 1949. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

North-China Daily News, an English-language newspaper in Shanghai, covers events in the city in 1949. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

He quickly jotted down in his notebook: "Amazing that Palu (Ba Lu, or the Eighth Route Army, as the PLA was often called at the time) haven't tried to enter the hotel. Their discipline is really something. How easy it would be for them to come in, set up some machine-gun on the roof or in the Bund-side rooms and blast the Garden Park Nationalist defenders."

After the three-day battle at Suzhou Creek, Powell and other residents of Embankment Building were relieved to find their homes intact. As well as being strictly instructed not to use heavy artillery inside the city to avoid causing damage, the PLA was not allowed to enter private property.

Landmark structures such as Broadway Mansion, the General Post Office Building and Embankment Building were left intact. Together with Suzhou Creek, they are some of the most notable sights in the city.

When the battle was over, Forman walked to Nanjing Road in downtown Shanghai and saw something even more surprising.

He described in his notebook PLA soldiers sleeping outdoors on Nanjing Road, instead of finding beds in hotels or private property.

"It's a touching scene. These youngsters must be dead tired marching and fighting for days and nights.… All afternoon they slept soundly along Nanjing Road on the sidewalks, a most incredible thing for a conquering army to do," Forman wrote.

North-China Daily News, an English-language newspaper in Shanghai, covers events in the city in 1949. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

North-China Daily News, an English-language newspaper in Shanghai, covers events in the city in 1949. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Key investments

Along with its buildings, foreign investment in the city was well maintained after the battle.

After Shanghai was forced to open to foreign powers in the middle of the 19th century, these nations made numerous investments in the city, some of them in public facilities such as water and power plants.

The Yangshupu Power Plant, an important facility that provided nearly 80 percent of the city's electricity supply, was one of them. It was run by the US-owned Shanghai Power Co.

In 1949, the plant was low on fuel and was running a heavy deficit, but the management team was more concerned about rumors that a "scorched earth" policy was being planned by the Kuomintang, who said they would destroy the power plant before they retreated, with the aim of leaving nothing for the CPC.

The team was also afraid of the Communists, because for dozens of years, the US had supported the losing side in the Chinese civil war.

After the Communists took control of the city on May 27, they tried their best to keep the power company running, much to the owners' surprise. The newly established People's Bank of China provided a loan for the power plant, while the new government hastily assembled coal supplies from other parts of China to keep the plant running.

Paul Hopkins, then-chairman of the Shanghai Power Co, wrote in his report to headquarters in the US, "There is no question the Communists are a new type of people who will ultimately bring great progress to China."

He thought they were "all significantly honest, hardworking individuals who lived on the barest essentials of food and clothing". He also found them "intelligent, very frank in discussing problems, and with a good sense of humor".

Hopkins later discovered that the only threat to the power plant came from Kuomintang air raids and a blockade.

In February, 1950, the plant was bombed in a major air raid by the Kuomintang forces. The attack resulted in more than 1,000 casualties, displaced over 50,000 people, caused massive power cuts and shut down businesses.

Speaking about making the documentary, Field said, "It is shocking to think that the Nationalists were willing to sacrifice the city to achieve their aims."

However, the heavy damage only served to highlight the effectiveness and resilience of the new government and strengthen people's determination to rebuild and develop Shanghai. The power plant remained in operation until 2010, when it was decommissioned to reduce carbon dioxide discharges as the city authorities pledged to go green and control air pollution.

The site and others still stand proudly on the Yangpu district waterfront, which has been transformed from an industrial rustbelt into an area of public spaces and attractive scenery.

Wang said, "We captured many fine images of the city and were also able to showcase the prosperity and glory of present-day Shanghai."