Former American interpreter and author captures the essence of Jia Zhangke's films, Yang Yang reports.

Director Jia Zhangke in action, a photo used in the book by American writer Michael Berry. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Director Jia Zhangke in action, a photo used in the book by American writer Michael Berry. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In the fall of 2002, Chinese film director Jia Zhangke attended the New York Film Festival for the screening of his film Unknown Pleasures. He was in demand-journalists and other directors wanted to interview and talk to him. Events were organized, such as post-show discussions, interviews with the media or meeting other directors such as Martin Scorsese. To make sure nothing was lost in translation, he needed an interpreter. Enter stage right, Michael Berry, a postgraduate student from Columbia University, who was hired for the role.

Gradually, Chinese cinema became one of the primary aspects of my research

Michael Berry, writer of the book An Accented Cinema, who’s also director of the UCLA Center for Chinese Studies

Berry knew Jia's work and was a huge fan of his films, especially Xiaowu (1998) and Platform (2000), which are "true masterpieces of contemporary cinema", Berry says.

Berry found these two films unforgettable, not only because of the director's mature cinematic technique and poetic framing, but also because every time he watched them, he would be immediately transplanted, as if in a time machine, back to 1993 and 1994, when he was a sophomore in college undergoing intensive Chinese language training at Nanjing University in East China's Jiangsu province.

"At that time, I watched a lot of films, but most seemed unreal. Although the two films were set in Fenyang, Shanxi province, they are the only two films that remind me of my experience in Nanjing, Jiangsu province-the sound, the music, the faces, the clothes and of course, the views," Berry writes in the introduction of his book An Accented Cinema, which has been published in China.

He has published seven books, including Speaking in Images: Interviews With Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers, Jia Zhangke's Hometown Trilogy, and Boiling the Sea: Hou Hsiao-hsien's Memories of Shadows and Light.

A photo of Jia (second from left) with the crew of Ash Is Purest Whiteis included in An Accented Cinema, a book by American writer Michael Berry, which has been published in China. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A photo of Jia (second from left) with the crew of Ash Is Purest Whiteis included in An Accented Cinema, a book by American writer Michael Berry, which has been published in China. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The idea that originated An Accented Cinema can be traced right back to the New York Film Festival, during which, apart from interpretation, Berry also did a two-hour interview with the director.

However, most of the interviews were done in 2018, when Jia was invited to Los Angeles for the China Onscreen Biennial. Berry was one of the curators and hosted six public discussions with Jia about eight of his films selected for the biennial, including The World (2004) and Still Life (2006).

In 2019, Jia made another visit to the United States before his film Ash Is Purest White was released in the US. Berry hosted another two discussions with him.

Based on the eight discussions and an interview in 2002, An Accented Cinema is divided into six parts which are organized chronologically.

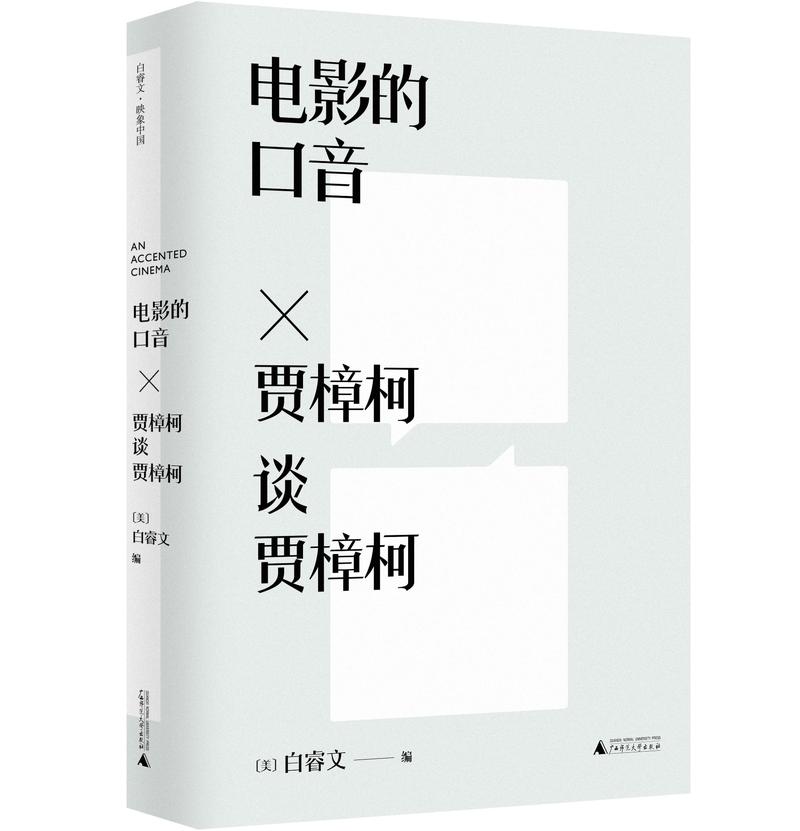

An Accented Cinema. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

An Accented Cinema. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

It offers a glimpse into how Jia grew up as a representative Chinese filmmaker, the inspiration behind his films, how he makes films and their wider influence.

In the interviews contained in the book, Berry cast his eyes on China, film, art, and Jia, writes Dai Jinhua, professor of Chinese language and literature with Peking University, in the preface of the book.

"While carefully looking and listening, Berry tried to catch and tell the accent in Jia's answers: (Are the accents) of China or of Shanxi's Fenyang? It seems that what Berry cares about more is the accent of individuals, art, film and style. It's Jia's accent or voice," Dai writes.

Berry is particularly interested in Jia's films, because "among filmmakers of his generation, he is one of the most intellectual", he says.

American writer Michael Berry. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

American writer Michael Berry. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

For him, Jia's work "is able to combine powerful images with challenging ideas-and that is something we don't see in the work of many of other filmmakers. In that sense, he is a true cinematic poet", Berry adds.

Although Jia's films address the reality of contemporary China, they are also about the human condition in universal ways, he says.

Another reason is that "Jia is always reinventing himself" and continually "searching for new ways of storytelling and new avenues of cinematic expression".

For the writer, there is also a personal reason.

"No matter how many times I visit China, part of my own imagination of 'China' is still deeply tied to the indelible memories from my student days in Nanjing during the early 1990s. Jia's early films, which are also a product of that era somehow were best able to capture the rhythm of life during that unforgettable era," Berry says.

A still from director Jia Zhangke's films A Touch of Sin. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A still from director Jia Zhangke's films A Touch of Sin. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

"In those films, Jia was able to single-handedly create some of the most memorable characters in contemporary film (like Xiao Wu and Cui Mingliang), reframe our understanding of realism in Chinese cinema, bring our attention to marginalized figures and locations, offer a deep meditation on the impact of radical social change, and create a new cinematic language," he says.

Growing up in suburban New Jersey in the 1970s, Berry occasionally saw old Chinese kung fu movies on television on Saturday mornings. However, when he was attending graduate school at Columbia University, where his original focus was contemporary Chinese literature, he started watching more Chinese films.

Later, he took courses at the Columbia University's film school with teachers like Richard Pena and James Schamus, the latter of which was Ang Lee's producer and screenwriter.

A still from director Jia Zhangke's films 24 City. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A still from director Jia Zhangke's films 24 City. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

"Gradually, Chinese cinema became one of the primary aspects of my research," says Berry, who's now director of the UCLA Center for Chinese Studies.

From 1998 to 2003, Berry often served as an interpreter for Chinese filmmakers and writers, such as Mo Yan, Su Tong, Zhang Yimou, Tian Zhuangzhuang and Jia.

While many other established Chinese filmmakers have embraced commercial films, Jia continues making art films, using the medium to raise difficult questions and often explores the possibility of new cinematic forms, Berry writes in the introduction of the book.

"Jia is one of the only directors from that period that has continued for the past 20 years to stay true to his early uncompromising artistic spirit. While others have slowed down, dropped out, or turned commercial, Jia continues to follow a path of artistic innovation," Berry says.

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn