This file photo dated May 3, 2021 shows a general view of Parliament buildings at Stormont, Belfast, Nortern Ireland. (PHOTO/ AFP)

This file photo dated May 3, 2021 shows a general view of Parliament buildings at Stormont, Belfast, Nortern Ireland. (PHOTO/ AFP)

DUBLIN/LONDON - A quarter of a century after unpalatable compromises ended decades of bloodshed in Northern Ireland, some of the architects of the Good Friday Agreement hope that deal can help inspire a route out of the region's near-permanent political crisis.

In April 1998, then British prime minister Tony Blair and his Irish counterpart Bertie Ahern helped Irish nationalists and British unionists craft an intricate powersharing deal that paved the way for militants on both sides to lay down arms.

The peace has utterly transformed the region, largely ending three decades of bitter violence that killed 3,600.

But the devolved powersharing government was struggling even before Britain's vote to leave the European Union altered the delicate political balance on the island of Ireland, and some fear the current boycott by the region's once-dominant Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) could prove fatal.

One source of the current political crisis is the sense that Brexit and its fallout have upset some of the balance of the 1998 deal - specifically the principle of cross-community consent embodied in a requirement for major legislation to be supported by a majority of both nationalists and unionists in the devolved assembly

Those who remember the repeated false dawns of 25 years ago are more sanguine.

"Nothing's ever irresolvable" said Blair, summing up the stubborn optimism many developed working in Northern Ireland at the turn of the millennium.

"Today... it's still very fraught but I think there's a depth to the process. There are roots that have been put down that I don't think anyone on the island of Ireland really wants to disturb," he told Reuters in an interview. "People realize that to go back to the past would be a complete disaster."

ALSO READ: UK, EU adopt new post-Brexit 'Windsor Framework' deal

Principle of consent

One source of the current political crisis is the sense that Brexit and its fallout have upset some of the balance of the 1998 deal - specifically the principle of cross-community consent embodied in a requirement for major legislation to be supported by a majority of both nationalists and unionists in the devolved assembly.

Nationalists, who are mostly Catholic, say Northern Ireland was wrenched from the EU in a UK-wide vote even though its smallest region voted 56 percent to 44 percent to remain.

Unionists, who are mainly Protestant and largely backed Brexit, say the imposition of trade barriers with the rest of the United Kingdom in a bid to avoid a hard border with EU-member Ireland was done without their consent.

That prompted the DUP to collapse powersharing a year ago, a position it has doubled down on in recent weeks in the wake of a reworking of post-Brexit trade rules under a compromise known as the Windsor Framework brokered by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.

With the DUP saying it won't return until major changes are made to the deal, and London and Brussels ruling that out, there appears no room for compromise. One DUP lawmaker said the EU-UK deal had effectively "ripped up" the 1998 accord.

The DUP was the only major party not to participate in the 1998 negotiations, but it later joined the powersharing government and went on to supplant the more moderate Ulster Unionists as the main voice of Protestant voters.

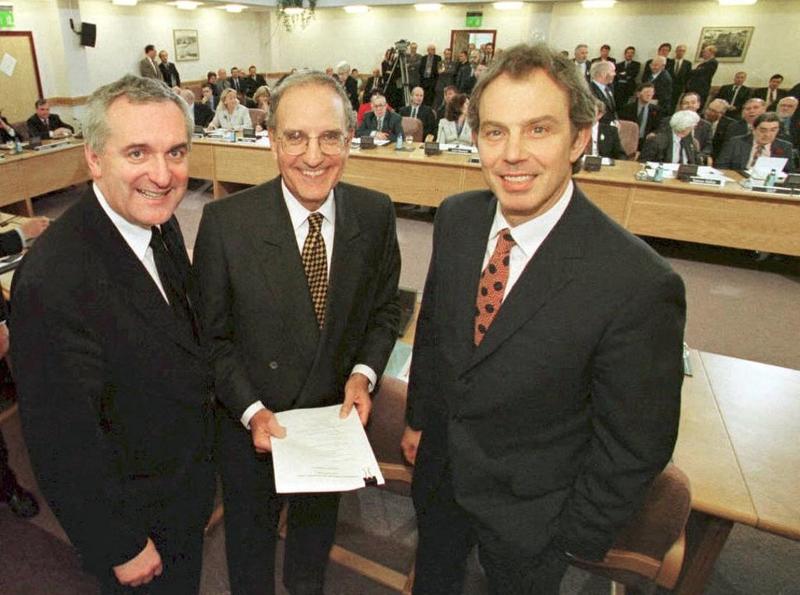

In this file photo taken on April 10, 1998, British Prime Minister Tony Blair (right), US Senator George Mitchell (center) and Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern pose for a photograph after signing an historic agreement - The Good Friday Agreement - for peace in Northern Ireland, ending a 30-year conflict. (PHOTO / AFP)

In this file photo taken on April 10, 1998, British Prime Minister Tony Blair (right), US Senator George Mitchell (center) and Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern pose for a photograph after signing an historic agreement - The Good Friday Agreement - for peace in Northern Ireland, ending a 30-year conflict. (PHOTO / AFP)

"There is an exhaustion and frustration," at the DUP's repeated objections, said Ahern, Irish prime minister from 1997-2008.

"But I've always looked on this in a pragmatic way that if there's a problem, try to fix it and I think we have to try and fix it. It's doable. It's bordering on the ridiculous, but let's try and do it."

ALSO READ: UK's Sunak in Belfast to start selling his new Brexit deal

There's no such thing as status quo. You're either going forwards or backwards ... If you stand still, what happens is eventually you fall over.

Bertie Ahern, former prime minister of Ireland

Stalemate

Many have identified the compulsory coalition that gives the largest party on either side of the sectarian divide the power to pull down powersharing as a key stumbling block to progress.

That, coupled with the rise of the Alliance party, which identifies as neither nationalist or unionist, has sparked calls for an overhaul of a political architecture premised on a society divided in two.

"There's no such thing as status quo. You're either going forwards or backwards," said Ahern, who believes a review is needed. "If you stand still, what happens is eventually you fall over."

The rules around devolution have already been changed in 2006 to overcome an earlier suspension.

But Blair said all sides must "proceed really carefully" with any reform and that the Brexit row has to be solved first.

'New Architecture'

Gerry Adams, another key player in the 1998 talks as head of the political wing of the Irish Republican Army, said he would be "very, very dilatory about making changes to the Good Friday Agreement".

But he said if the DUP, the key rival of his Sinn Fein party, does not re-enter government, other options would have to be considered.

"If they are not going to do so, then let them tell us that and then we'll all move forward into a different architecture because there can be no going back to what's described as direct (British) rule," Adams told Reuters.

READ MORE: UK PM 'pleased' with progress on Northern Ireland protocol talks

Adams, who has always denied membership of the IRA, is also optimistic, but for a different reason: his party has said it expects the British government to call a referendum on Northern Ireland breaking away from British rule within a decade.

The 1998 agreement requires London to call such a vote if it seems likely a majority would back Irish unity.

"Sands are shifting," said Adams.

Despite the current crisis, "a space has been opened up where people can moderate our differences politically", the former Sinn Fein leader said.

"We have been able to develop a pathway to change which will lead to greater change, I believe, in the time ahead."