Hong Kong-based artist captures the spirit of the city by blending Chinese masters and Monet in her work

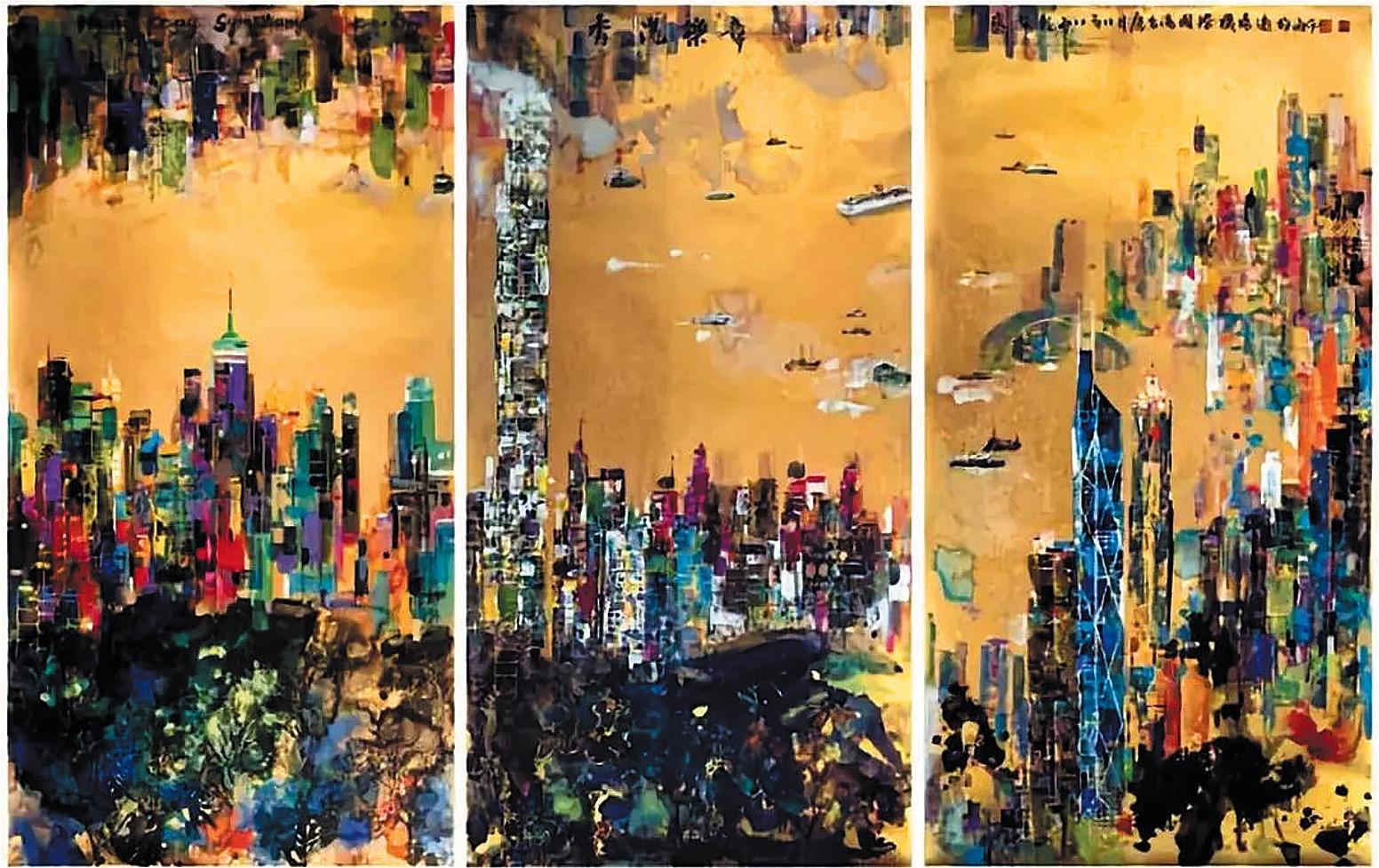

The 2-meter-high Chinese painting by artist Kuku Chai Bu-kuk, commissioned by Hong Kong International Airport in 2011, is on permanent display in the airport's Terminal 1. The artist's skillful use of Chinese ink, watercolor and monotyping techniques presents a spectacular view of Hong Kong's iconic Victoria Harbour as seen from The Peak. The melding of traditional and contemporary techniques portrays a modern and futuristic city. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The 2-meter-high Chinese painting by artist Kuku Chai Bu-kuk, commissioned by Hong Kong International Airport in 2011, is on permanent display in the airport's Terminal 1. The artist's skillful use of Chinese ink, watercolor and monotyping techniques presents a spectacular view of Hong Kong's iconic Victoria Harbour as seen from The Peak. The melding of traditional and contemporary techniques portrays a modern and futuristic city. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Hong Kong-based Chinese artist Kuku Chai Bu-kuk talks her students through a mesmerizing artistic odyssey in her austere-looking studio in North Point on Hong Kong Island. She dismantles the artistic language that defines her signature style, layer by layer, until it is cut to the pith — “zeitgeist” and “East-meets-West” — its own tribute to the special administrative region’s art and culture.

Chai, an arts consultant with the Hong Kong Arts Development Council and director of the China Artists Association, has left the footprint of her works — paintings on paper or porcelain — across the globe through exhibitions, auctions and collections. Her works have become a permanent collection at the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government’s London office, while former HKSAR chief executive Tung Chee-hwa collected Chai’s works, with one depicting Hong Kong’s cityscape in gilded hues on display at Government House in Central — the official residence of the HKSAR’s chief executive.

Chai's works are a blend of the painting styles of Chinese realism and Western impressionism, offering a glimpse of the artist's eclectic mindset, which she has been dedicated to imparting to budding artists in Hong Kong and the mainland. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chai's works are a blend of the painting styles of Chinese realism and Western impressionism, offering a glimpse of the artist's eclectic mindset, which she has been dedicated to imparting to budding artists in Hong Kong and the mainland. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Those who arrive in Hong Kong by air are likely to be greeted by the futuristic Hong Kong Symphony — a giant wall of paintings at Terminal 1

of Hong Kong International Airport, framed in LED panels, capturing the glitz of the city’s dense forest of skyscrapers and the glimmer of its landmark Victoria Harbour. The brainchild of Chai, it is inspired by ink and watercolor paintings, as well as monotyping, and is a showcase of her talents and ethos.

By any stretch, Chai’s works are the face of Hong Kong’s art and cultural resume. The wanderlust nature of her artistic pursuits and the expansive reach of her artworks embody the SAR’s cultural influence on a global setting.

But boiling Chai’s artistic style down into a category or genre does little justice because it distills the artistic finesse of the East, primarily China and Japan, and the technical and aesthetic influences of the West that she had spent more than four decades trying to absorb and assimilate.

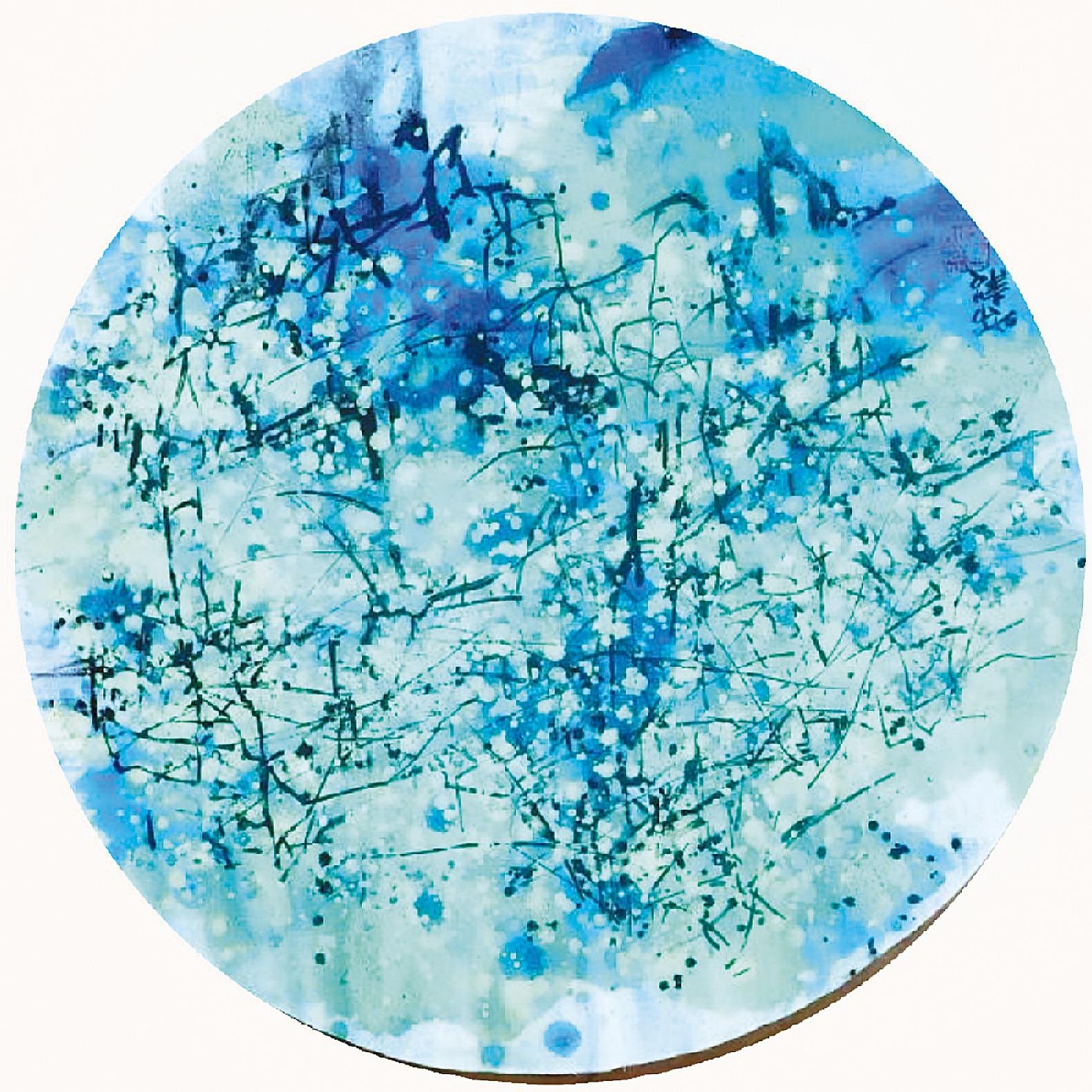

Chai channels her "East-meets-West" artistic language on ceramics, an immaculately slick alternative medium to paper canvas.(PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chai channels her "East-meets-West" artistic language on ceramics, an immaculately slick alternative medium to paper canvas.(PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

If asked to name the most profound influences on her artistic lexicon, Chai would give credit to three legendary figures from China — Fu Baoshi, Zhang Daqian, Ren Bonian — and France’s Claude Monet.

Spearheading the New Chinese Painting Movement dedicated to modernizing the traditional Chinese style, Fu Baoshi (1904-65) changed landscape ink painting by splattering and throwing ink or paint onto the canvas. It is this “throw-it-against-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks” artistry and his dexterity with paintbrushes that made Chai sit up and take notice in her early art career.

“Instead of using ink-soaked brushes, Fu applied and slithered brushes with dry and tough tips against the paper to create a slightly granular and coarse texture, rendering the mountain ridges abrasive, stoic and grandiose,” she said, adding that she is astonished by such a novel execution of brushes in Chinese painting, which surprisingly imbued the natural landscape with a human-like temperament.

Chai's works are a blend of the painting styles of Chinese realism and Western impressionism, offering a glimpse of the artist's eclectic mindset, which she has been dedicated to imparting to budding artists in Hong Kong and the mainland. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chai's works are a blend of the painting styles of Chinese realism and Western impressionism, offering a glimpse of the artist's eclectic mindset, which she has been dedicated to imparting to budding artists in Hong Kong and the mainland. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The “splashing technique” mastered by Zhang Daqian (1899-1983) was another early inspiration for Chai, with ink and colors spattered with wild abandon, creating an embellishing and cascading effect, with the contours melding into a blurry periphery. “The willfully abstract depiction of nature created an ethereal aura that was hardly achieved in conventional Chinese paintings,” said Chai.

Ren Bonian (1840-96), although bearing the hallmarks of Chinese realist paintings, was one of the early bastions of the Western freestyle in China. “So exquisitely down-to-earth and accessible was his art that it garnered a wide reach. His versatility and his works’ capacity of resonating even with the uninitiated impressed me,” recalled Chai.

These three iconic Chinese artists share a common denominator despite being prominent in different periods of history. “They were all a bit ahead of their time, and were trailblazers in their quest for a ‘zeitgeist’ and future-proof artistic voice,” said Chai. “An art without a zeitgeist relevance is doomed to be the denominator of the era, meaning being easily eclipsed and obliterated,” she said.

Chinese artist Kuku Chai Bu-kuk cut her teeth on painting from childhood under her family's artistic influence and came to Hong Kong in the 1990s, pioneering art education and establishing her artistic presence across the world. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chinese artist Kuku Chai Bu-kuk cut her teeth on painting from childhood under her family's artistic influence and came to Hong Kong in the 1990s, pioneering art education and establishing her artistic presence across the world. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In the constantly evolving art realm, Chai said, artists have to keep their ears to the ground, casting their vision beyond the original locale of their cultural exposure, extracting and appropriating the wisdom of other cultures in a good way, to ensure that their art has an enduring relevance.

“I can’t simply copy the works of the three Chinese art virtuosos. But how could I possibly go a step further?” Chai asked. She found the answer at Paris’ Musee de l’Orangerie in the 1990s.

Her eureka moment came the instant she saw the masterpieces by Claude Monet — the “Father of the Impressionism Movement”.

“I vividly remember standing in front of his Water Lily Pond, fixated, overwhelmed, petrified, lost for words … with tears welled up in my eyes,” Chai recalled, saying she will never forget that euphoria of serendipity as if being able to bottle lightning.

“I felt as if an electric current passed through my body all the way to the top of my head, where a window was flung open to a new world,” she said, describing the encounter as “life-changing”. The glimmer of light and reflection of the sky flickering on the water, the serene crystalline water that extends to unperceivable borders, defined brilliantly by the gradation of light and shade captured by Monet from dusk to dawn, touched her soul.

“It dawned on me how potent an exact depiction of light and shadow could be to coax the idyll out of the painted landscape and trigger a visceral pleasure in viewers, which wasn’t emphasized in early Chinese painting,” said Chai. She explains that the idea of a light spectrum was on people’s radars earlier in the West than in China.

“A viewer would expect to see the vein of mist shrouding a bamboo bush, catch a whiff of aroma from a teapot, feel the haze enveloping the rolling mountains. Such sensory pleasures have to be given weight in a painting in equal measure with the precise depiction of the objects.”

Chai channels her "East-meets-West" artistic language on ceramics, an immaculately slick alternative medium to paper canvas.(PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chai channels her "East-meets-West" artistic language on ceramics, an immaculately slick alternative medium to paper canvas.(PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Her mental block in art creation was solved by fusing the sophistication in Chinese realist paintings with the prowess in the Western impressionist style, highlighting the subtlety of light and shadow.

“Well,” said Chai, clapping her hands, “It’s time to cut to the chase, talking about my porcelain painting!” Without understanding the genesis of her brushstrokes on paper, you would not be able to grasp the ingenuity of her “artistic porcelain”.

The “juxtaposition of East and West” is Chai’s signature theme, while the medium for communicating the eclectic idea is not confined to paper. Transcending both utility and ornamental purpose, porcelain, to her, is an immaculate alternative to canvas paper amplifying the “East-meets-West” ethos, and a clean slate for her artistic flair to be awakened afresh.

Nevertheless, it is far from straightforward to translate the brushstroke techniques employed in painting onto ceramics because it takes repetitive firing and drying in the kiln, during which myriad colors are applied layer by layer. How the colors interact with each other and make their presence felt hinges on the temperature of firing, the humidity of the ceramic surface and the artist’s sensibility to hues and command of the paintbrush.

It is a Herculean feat to choreograph the movement of colors to achieve the intended effect. If the surface is too damp, colors will muddle together in a blur, she said. If it is left to dry for too long, each pigment will stick to the parched surface in isolation, with contours rigidly defined, where the subtlety and fluidity embodied in impressionism are lost.

Everything has to be “just right” in the art of porcelain painting, she said. It is quite an art of “accuracy” and “precision”.

Her porcelain is from Liling, a county-level city in Hunan province, and what sets it apart from other regions or countries is its purity and slickness. Cradling a dainty teacup molded out of Liling ceramics, and swirling it gently under a beam of light, Chai explained: “Look at the translucent, almost see-through body. You can barely spot any blemish or minute dent.”

The abundance of assorted natural minerals in Liling is a rich seam to mine for porcelain painting as they provide a palette of vivid colors. Moreover, the paints sourced from the local natural minerals are edible, Chai said, making them safe for domestic use.

Chai channels her "East-meets-West" artistic language on ceramics, an immaculately slick alternative medium to paper canvas. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chai channels her "East-meets-West" artistic language on ceramics, an immaculately slick alternative medium to paper canvas. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Liling, famed as one of China’s three “ceramic capitals”, along with Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province and Dehua county in Fujian province, boasts a 2,000-year history in ceramic production. While Jingdezhen might be synonymous with Chinese ceramics, Chai noted that Liling porcelain ware is a contemporary representation, omnipresent in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

A petite cup that could sit in a palm takes pride of place on Chai’s workbench, where a Lionhead Goldfish — a symbol of wealth and harmony in Chinese culture — appears in glowing relief. Its crimson-hued head crown and fluttering giant tail in cherry blossom color bring it to life.

“Touch it,” Chai said before handing it over. It turns out that the black specks of fish scale jut out of the surface slightly, turning the ware palpably textured and animated.

“The paints have extractions of agate and emerald which, when fused with gold, can better dissolve,” she explained. “It’s fired at 1,380 C, sharp — neither higher nor lower. Only the pitch-perfect temperature can yield the desired watered-down colors and render a hazy effect to create gradations between different colors (seen in impressionist art).”

In essence, Chai is grafting Chinese realism and Western impressionism onto her porcelain. Her approach on paper still applies to ceramics, while the “water” as a medium to meld the colors on paper is substituted with “fire” or “temperature” in painting china.

A closer examination of her porcelain painting following her explanation leads to more discoveries — the goldfish’s tail unfurls like a velvety plume as the pinkish shades of color fade into the periphery; the fall leaves, ablaze in shades of color, from chrome yellow to amber to a residue of fiery red and to something in between, transport one to the restful autumn; a basin ornate with a boldly colored lotus flower punctuated with dragonflies and frogs in pops of color is brimming with vitality that is about to spill over the edge.

A graduate of the Art College of Nanjing Normal University — one of the pioneering academies promoting art education in China — Chai has carried on the mission of art education. Apart from teaching in private workshops, she is an instructor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies, adjunct professor of the Beijing Institute of Technology, and a visiting professor at Xinjiang Normal University.

“Imparting and articulating the ‘East-meets-West’ artistic essence with accessible eloquence to emerging artists is nothing short of a skill. But, I’m blessed with the vantage point offered by Hong Kong to pollinate the eclectic mindset in the multicultural artistic garden,” enthused Chai.