The world’s biggest single-site solar power plant in Abu Dhabi, built with Chinese equipment and expertise, underlines the United Arab Emirates’ commitment to deal with climate change and attain its decarbonization goals. Wang Yuke reports from Hong Kong.

The neatly installed photovoltaic solar panels expected to provide 160,000 households in Abu Dhabi with clean electricity, form a stark contrast to the desert. (ZHU WEIJIE/ CHINA DAILY)

The neatly installed photovoltaic solar panels expected to provide 160,000 households in Abu Dhabi with clean electricity, form a stark contrast to the desert. (ZHU WEIJIE/ CHINA DAILY)

In an unbounded desert some 50 kilometers from downtown Abu Dhabi, there is nothing but neatly arranged rows of solar panels, surrounded by lattice towers, with some sophisticated utilities at the far end of the infinite environment, as well as undulating dunes.

You are left stunned by the isolation, the immensity of Mother Nature, amid the sprawling 21-square-kilometer stretch of terra firma.

However, unlike barren deserts, this vast land, equivalent to 2,800 soccer fields in area and more than an hour’s drive from the United Arab Emirates capital, radiates vitality.

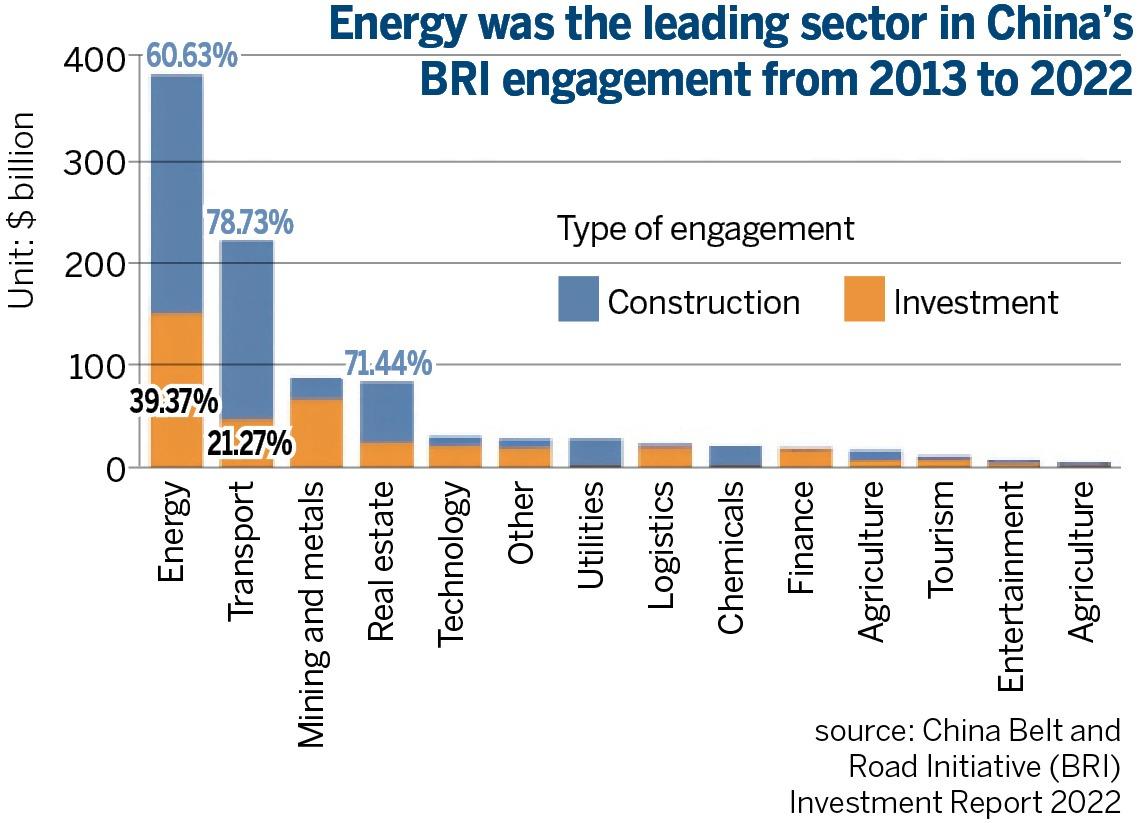

The 2-gigawatt Al Dhafra PV (photovoltaic) solar power plant — the largest single-site photovoltaic power plant in the world — lights up about 160,000 households with a constant supply of clean electricity. The brains behind this mammoth venture are 5,000 manpower assigned to the Belt and Road Initiative — a global infrastructure development strategy launched by China in 2013 to link up Asia with Africa and Europe to drive trade and economic growth.

Venturing into the scorching summer heat of up to 43 C takes guts. Just a few minutes’ exposure to the uncompromising ultraviolet rays and heat could set you on fire and give you vertigo. The sun’s glare is so piercing that, without sunglasses, your eyes would sting and run dry.

It was a real baptism of fire that a PV solar project of such gargantuan magnitude and significance was completed amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the heat.

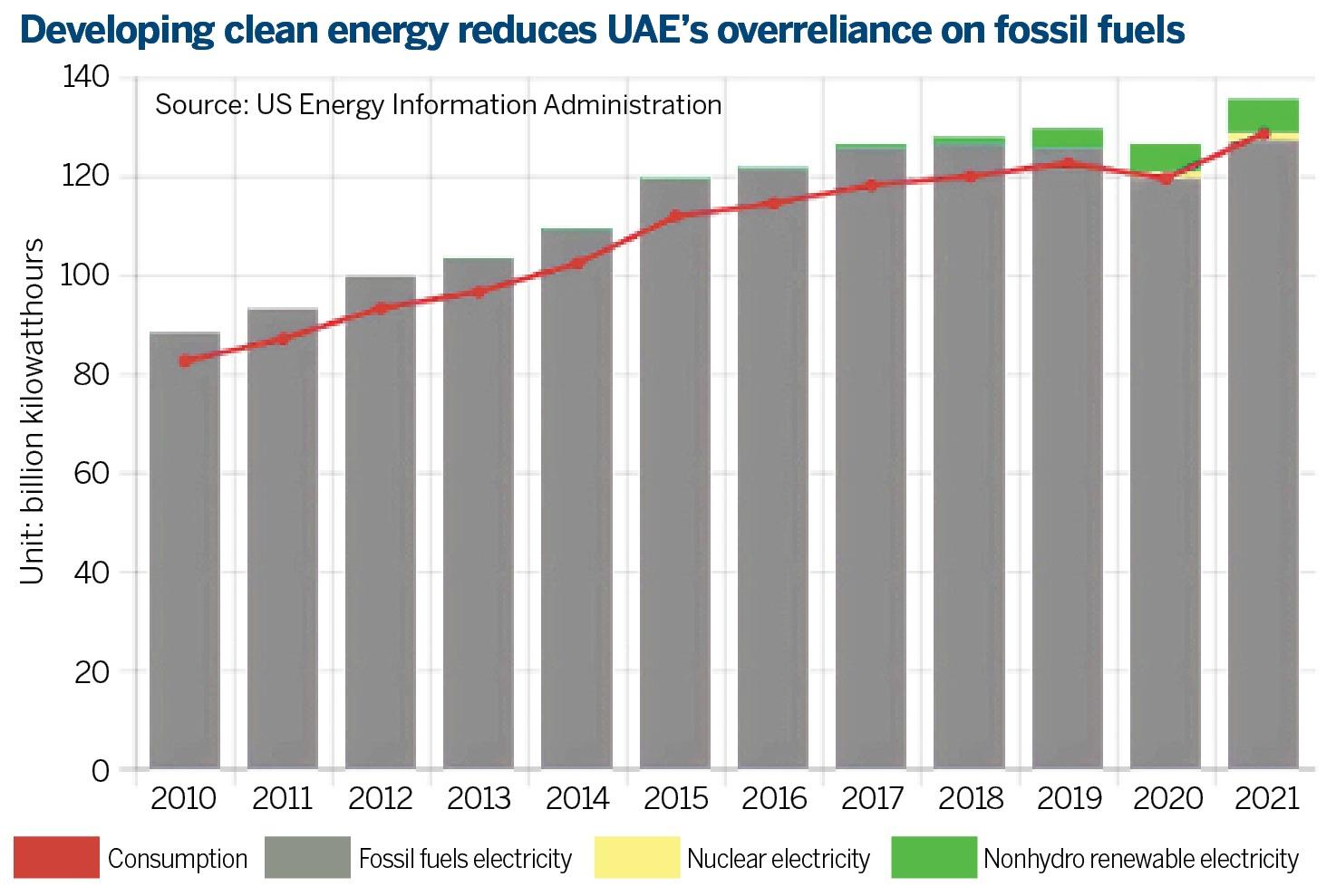

Why is the UAE — an energy giant with its vast fossil fuel reserves a rich seam to mine — so bent on undertaking an energy transition to become a global clean energy powerhouse?

Loai Sharkawi (in kaffiyeh, a traditional Emirati men’s headdress), an EPC construction manager of the Al Dhafrah solar power project in Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, exchanges ideas with fellow engineers. It is a staple of their everyday routine. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

Loai Sharkawi (in kaffiyeh, a traditional Emirati men’s headdress), an EPC construction manager of the Al Dhafrah solar power project in Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, exchanges ideas with fellow engineers. It is a staple of their everyday routine. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

There is a real need for change, contends Abdulaziz Alobaidli, chief operating officer of Masdar — the UAE’s flagship renewable energy company and a major developer of the Al Dhafra solar power project. The UAE has benefited from the underlying “wisdom of its leadership”, which has been very dynamic in “thinking about the future”, says Alobaidli.

“We need to diversify our economy and energy resources to enhance our energy security,” he says, as relying on a single source of energy is just too risky. Therefore, decarbonization is a “necessity” rather than a “luxury” or “privilege”. “We’re committed to decarbonizing the value chain of all processes relating to energy, upstream and downstream.”

Most importantly, says Alobaidli, since climate change is a global issue, the UAE feels compelled to share its knowledge and solutions with the world to support collective efforts to reach net zero by 2050. This is a tenet of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

Wang Jinwei, general manager of the Abu Dhabi branch of Beijing-based China Machinery Engineering Corporation Group, explains that fossil fuels, while being a carbon-intensive resource for electricity, are subject to market fluctuations and don’t promise a secure supply of electricity. Hence, the “Clean Energy Strategic Target 2035”, initiated by Abu Dhabi’s Department of Energy, envisions 60 percent of the region’s electricity being generated from clean and renewable sources by 2035. The projection is the first legally binding clean and renewable energy target in the Middle East, and integral to Abu Dhabi’s energy transition process.

Resolved to do its part for the “Green Silk Road”, CMEC secured the $1 billion engineering, procurement and construction contract to build the 2GW Al Dhafra solar photovoltaic project in Abu Dhabi in October 2022.

Loai Sharkawi (in kaffiyeh, a traditional Emirati men’s headdress), an EPC construction manager of the Al Dhafrah solar power project in Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, exchanges ideas with fellow engineers. It is a staple of their everyday routine. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

Loai Sharkawi (in kaffiyeh, a traditional Emirati men’s headdress), an EPC construction manager of the Al Dhafrah solar power project in Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, exchanges ideas with fellow engineers. It is a staple of their everyday routine. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

The world’s largest single-site solar photovoltaic plant, now in full operation, is expected to help Abu Dhabi slash its annual carbon emissions by 2.4 million metric tons, raising the proportion of clean energy in the UAE’s total energy mix to more than 13 percent. This is equivalent to removing about 470,000 cars from the roads.

This huge swathe of desert is not distant nor silent. Apart from on-site workers clad in florescent vests, protective high-top caps, and thick and rubber-soled boots, the relative serenity is punctuated from time to time by creaks and squeals.

Scratching our heads to try and figure out where these sounds came from, Wang tells us: “They’re from the solar modules (panels) rotating in sync with the sun radiance shifts throughout the day. Capturing the largest possible amount of sunlight ensures the maximum generation of electricity. No solar energy should be wasted.” So, the solar panels come into varying slopes throughout the day, the steepest being at dusk and dawn, he says.

While the panels’ movement was too subtle to detect, the unrelenting noises are a tell-tale sign of the desert’s vigor and tirelessness in lavishing the city with a clean life.

When the panels lie flat peacefully, face up, at around 7 pm each day, the panel cleaning routine commences. The film of sand collected on the panels’ surface would obstruct its absorption of rays and subsequent electricity generation, explains Wang. So, dusting off the panels is important.

While water is the conventional answer to having the panels cleaned, it doesn’t apply in Abu Dhabi due to the city’s meager rainfall. “Thus, we come up with cleaning robots, an automatic substitute, after brainstorming with locals who’re more acquainted with the local natural conditions,” says Wang.

Wang Jinwei, Abu Dhabi branch general manager of the solar power project’s contractor China Machinery Engineering Corporation Group, demonstrates the last module of the photovoltaic solar panel, which completes the construction and bears the signatures of all participants in the project. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

Wang Jinwei, Abu Dhabi branch general manager of the solar power project’s contractor China Machinery Engineering Corporation Group, demonstrates the last module of the photovoltaic solar panel, which completes the construction and bears the signatures of all participants in the project. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

Record-breaking feats

Unfazed and unaffected by the onslaught of COVID-19, the Al Dhafra solar power project testifies to China’s expertise and competence. It reinforces how the country’s solar manufacturing business is supporting regions involved in the Belt and Road Initiative to meet their zero-carbon targets. “What I’m saying is no more perception. It’s reality,” says Alobaidli.

The solar project has put the prime China-UAE duet on the Belt and Road map with many records broken in the process.

Against all odds during the pandemic, with global supply chains thrown into disarray, CMEC managed to complete the Al Dhafra project on time. “We were installing almost 20 megawatts daily, setting a record. When we started our journey with renewable energy, specifically solar energy in 2010, it took us one year to build a 10-megawatt plant here in Masdar city. In the large-scale Al Dhafra PV project, thanks to experienced contractors such as CMEC, we were able to install 20 megawatts every day,” recalls Alobaidli.

The project involved procuring four million bifacial solar PV modules from the Chinese mainland to be mounted on 30,000 single-axis sun trackers. “More than 10,000 containers had to be used to ship the modules despite the erratic logistics network. It was challenging,” reminisces Wang. The pandemic-induced disruption was just a tip of the iceberg in a Herculean task. The complex and varied topography across the sweeping desert posed a plethora of engineering hurdles, he says.

A pile driver is used to set solar panels. The desert in Abu Dhabi poses numerous obstacles to the construction, all of which are being addressed. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A pile driver is used to set solar panels. The desert in Abu Dhabi poses numerous obstacles to the construction, all of which are being addressed. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The site’s proximity to the sea also means the underground soil is highly saline and alkaline. To protect the piles, whose ends go deep into the ground, from erosion, concrete had to be poured into the hole during piling works.

The high water level to the northeast would cause the soil to collapse when piling and sunken soil choked the burrowed holes. A solution eventually surfaced — inserting a plastic tube to anchor the soil before burrowing.

Loose soil in the dune-dominated southeastern region was a knotty problem until it was displaced and substituted with concrete to get a more stable structure.

Building the 400 kilovolts GIS (gas-insulated switchgear) substation was also demanding. “It had to be put under the scrutiny of Abu Dhabi Transmission and Despatch Company, which adheres to (one of the most) rigorous, hard and fast standards,” says Wang.

The rigorous vetting and approval process was a problem too, slowing down construction. “But we still made it within 22 months, which would have been 35 months under the local timeline. It had registered 14 million safety work hours by early June,” he says.

The plant serves as a “blueprint” for Abu Dhabi’s upcoming projects of the same size and magnitude, says Alobaidli.

Beyond its environmental merits, the project has turned Abu Dhabi’s labor market into a hubbub, says Alobaidli. “At its peak, we had more than 4,000 workers from various countries residing in the UAE. A lot of local subcontractors benefited from the project and offered full-time jobs for the people.”

A group photo of all the engineers and other personnel involved in the Al Dhafrah project — the world’s largest single-site photovoltaic power plant, which is a testament to the collective efforts of the “big family”, as the engineers refer to it. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A group photo of all the engineers and other personnel involved in the Al Dhafrah project — the world’s largest single-site photovoltaic power plant, which is a testament to the collective efforts of the “big family”, as the engineers refer to it. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

‘Reciprocal relationship’

If you find the solar plant too remote in your life as its impact may not be immediately felt, you may want to go on a tour of Abu Dhabi, mindful of the charging stations as a fixture of the cityscape. The city has set concrete decarbonizing transformation strategies for its transportation system. “With our partners, we look to ensure an entire zero emission fleet of taxies by 2040,” declares Abdulla Al Marzouqi, director-general of Abu Dhabi’s Integrated Transport Centre, a subsidiary of the Department of Municipalities and Transport.

Shenzhen, which Al Marzouqi hails as one of the few successful stories of green public transport transformation, will be the key model for the UAE to take a leaf from. Shenzhen Bus Group is the first and largest pure electric transport operator with about 10,000 electric vehicles, and “they will provide us with support and guidance — from drafting electric transport policies to assessing electric transport operational efficiency,” he says.

Chinese mainland companies in the new energy sector are taking intellectual and technical assets, as well as technological standards, overseas today — “from upstream, like solar energy production and energy storage services, to downstream, where EV companies are coming to the Middle East,” says Hallie Liao, general manager of KMB International Inc, parent company of Shenzhen Bus Group.

The desert has morphed into an energy powerhouse filled with rows of solar panels. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

The desert has morphed into an energy powerhouse filled with rows of solar panels. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

In the exhausting battle with climate deterioration, China has gone out of its way liaising with countries and regions involved in the BRI, hoping to haul humanity back from the cusp of possible annihilation by climate change. But the country runs the gauntlet of international naysayers discrediting it for intensifying its grip on the renewable energy chain.

Rumors can be damaging, but they would easily crumble if everyone in the know smashes them and defends the wronged side.

Loai Sharkawi — an EPC (engineering, procurement and construction) construction manager of the PV solar project — has a say in the crowdsourcing and cross-pollination of wisdom entrenched in the partnership.

Gathering at an oval table, where an oversized strategy map was unfurled, with a projector flickering overhead, Sharkawi led a crew of engineers, contractors and suppliers, gesticulating, scribbling notes, picking each other’s brains in a frenzied discussion. Inspecting the “Road Map”, as Sharkawi calls it, and brainstorming feasible fixes when work deviates from its expected course is a daily, weekly and monthly routine, he says. There is a free flow of know-how and transparency of techniques there, without the need to keep knowledge and information to oneself, which Sharkawi appreciates.

All the skills picked up from the project will translate into brownie points glamorizing his resume. “I’ll carry it along into my future career, future projects, other companies, developers and owners … to help make the planet green.”

“As a technology agnostic company, we’re open to work with manufacturers, investors, EPC partners from all over the world. We haven’t ever been finding ourselves in a difficult situation where we have to work only with Chinese (entities),” clarifies Alobaidli. What drives them to lay a sustained partnership, he says, is when they see the technical and economic value the partner could bring, and the contractor or investor is on the same wavelength, which is a recipe for the collaboration with China.

“China is on the top of clean energy innovation, with its forte being cost-effective manufacturing facilities — high-capacity factories to produce solar panels,” says Quentin des Cressonnieres, general manager of Engie Services Kuwait.

In an open-source world, there is little concealment of information and knowledge. “With Chinese contractors and all the others as well, we could maintain a very transparent and reciprocal relationship,” he says.

There have always been skeptical noises around “because everyone (from the international community) wants the whole piece of the cake. They don’t want to share it with you, but Chinese policies for BRI are all about sharing,” argues Professor Man Hau-chung, dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. “We’re helping those developing countries along the Green Silk Road to build infrastructures and develop renewable energies and transport,” which are their lifelines, says Man, who envisages a more powerful dynamic in green energy globally.

The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, a landmark of Abu Dhabi, is a blend of different Islamic architectural schools. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, a landmark of Abu Dhabi, is a blend of different Islamic architectural schools. (ZHU WEIJIE / CHINA DAILY)

Hong Kong’s contribution

The crusade for renewable energy and sustainable solutions will be an enduring signature trend of this era worldwide. The Belt and Road, rebranded as the Green Silk Road, pools all the collective wisdom — talents, expertise, leadership, contacts and funds — Man contends.

Hong Kong’s high-caliber universities are keenly aware of pivoting their studies and education on the most pressing and zeitgeist challenges, renewable energy and sustainable living included. The Belt and Road Advanced Professional Development Program in Power and Energy, co-launched by PolyU and Xi’an Jiaotong University, State Grid Corporation of China and Hong Kong Electric in 2018, has so far attracted nearly a thousand energy professionals from up to 30 countries and regions, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. The five-day technical training, practice exchanges and collaborative innovations unite these global elites in consolidating energy transition and energy security. Hong Kong makes its presence felt on the Green Silk Road through its power of rallying and education, says Man.

Infrastructure projects in the developing countries along the green route are on a mammoth scale, involving prohibitive expenditure. As Hong Kong boasts having the world’s freest and most stable currency exchange, the international financial hub is a natural magnet for investment and equity financing, notes Michael Zhang Zhenyu, director of the Hong Kong office of Sinomach — CMEC’s parent company.

Zhang said he believes the city’s robust legal and financial systems that provide high-level protection for investors in high-risk and high-cost transnational projects, will help BRI projects secure the special administrative region’s coveted financial rewards. “In the past five years, our Hong Kong company has helped secure around HK$1.6 billion in equity investments for infrastructure projects in the B&R countries,directly driving a financing amount of HK$ 30 billion for the B&R projects,” he says.

As we dwell on the avalanche of doomsday theorists pontificating about depleting fossil fuels, a future atmosphere choked with carbon emissions, and humanity’s submission to fatal plagues, set against today’s impenetrable hazy skyline, we can take solace from the desert Abu Dhabi has transformed into a solar energy powerhouse, and that a frisson of clean energy along the Belt and Road Initiative is in the offing. But there is no room for complacency.

Contact the writer at jenny@chinadailyhk.com