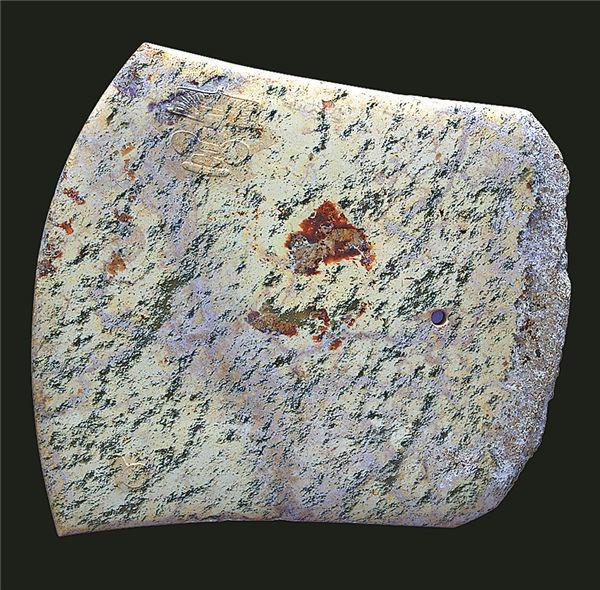

A Liangzhu jade plaque ornament bearing the man-and-beast pattern. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

A Liangzhu jade plaque ornament bearing the man-and-beast pattern. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

It let its weight be felt the very moment it was unearthed and lifted out of the soil, under which it had been buried for some 5,000 years. Next was its fantastical beauty, of which a tantalizing glimpse was gained by Qiang Chaomei, as she stared at it through her camera, zooming in on the mind-boggling lines engraved across its surface.

"At the time we were working with rather primitive photography equipment: the light was anything but soft, yet it somehow helped to bring out all the details vividly and sharply," she recalled in 2022, 36 years after the discovery thrilled the Chinese archaeological world.

"There they were — the feathered crown and the extraordinarily big eyes rendered in relief, the threadlike lines that filled up the spaces ... I traced those lines through the viewfinder before arriving at what seemed to be the elbow of a bent arm, toward the end of which was a well-defined hand with four fingers and a thumb!"

As an astounded Qiang zoomed out, another arm entered the frame: the pattern was symmetrical, containing a striking sense of solemnity befitting the rarity of its material — jade.

Liangzhu's "king of all cong". (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Liangzhu's "king of all cong". (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

The object is known as a cong, the word denoting a particular form of ritual jadeware, which typically features a cylindrical tube encased in a square prism. To be exact, this particular piece is known as "the king of all cong", thanks in equal part to its mass — it weighs 6.5 kilograms — and minute details. The man to whom it had belonged — the occupant of a tomb dated to around 3000 BC — is believed to be among those behind the construction of the ancient city of Liangzhu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in today's Hangzhou, Zhejiang province.

The jade fitting for a scepter. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

The jade fitting for a scepter. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

The sprawling site, located in the Yangtze River Basin near China's southeastern coast, is home to a civilization whose influence was felt across centuries. It has also revealed an early regional state from late Neolithic China with a unified belief system, according to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention.

Proof for that shared spirituality of the state, which existed for roughly a millennium between 3300 BC and 2300 BC, was carried by the cong, whose mysterious pattern depicts a manlike figure donning a bristling feather crown and rising above a wide-eyed, bar-mouthed beast. The same pattern was repeated 16 times across the surface of the artifact: twice on each of the four sides and twice across each of the vertical edges. (Those across the edges depict a simplified version, with the human figure reduced to just two eyes and a mouth.)

"It's not as though any other jade artifacts bearing the same man-and-beast motif had never been encountered. They had. But none of them had spoken so distinctly and powerfully as to catch the attention of the archaeologists," says Wang Ningyuan, who has worked in Liangzhu since 2000 and today leads the excavations conducted at the site.

The ultimate Liangzhu emblem is composed of a manlike figure rising above a mythical beast. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

The ultimate Liangzhu emblem is composed of a manlike figure rising above a mythical beast. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

"The jade cong's discovery in 1986 was crucial: it didn't take long for people to look around and realize that this is a recurring theme. In fact, it's ubiquitous," continues the 55-year-old, who has just compiled an oral history comprised of the recollections of those involved with the Liangzhu site over the past four decades, including Qiang and himself. It is due to be published later this year.

Among other items, the pattern can also be found on a jade axe (known as yue) and a scepter unearthed from the same tomb. Although the wooden sections for both items have long turned into dust — in the case of the scepter, only the jade fittings remain — archaeologists were able to piece together the disparate parts that lay not far from each other.

A Liangzhu jade shaped like a crest bearing a simplified pattern of the beast. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

A Liangzhu jade shaped like a crest bearing a simplified pattern of the beast. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Liangzhu's "king of all cong", with a simplified version of its man-and-beast image displayed across the edge. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Liangzhu's "king of all cong", with a simplified version of its man-and-beast image displayed across the edge. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

All three artifacts are part of an exhibition held by the Shanghai Museum focusing on the Liangzhu culture.

Judging by the items' relative position to the human skeleton upon their discovery, it seems that the deceased had rested his head upon the jade cong, while holding the axe, with the scepter placed horizontally across his chest. "From the stone axe, something Liangzhu people worked with and fought with, evolved the jade axe, a symbol of military might. Its proximity to the jade scepter — clearly representing kingly power — and the jade cong suggests an overlapping of the worldly and the ethereal," says Wang. "This is someone who had assumed the status of a divine ruler."

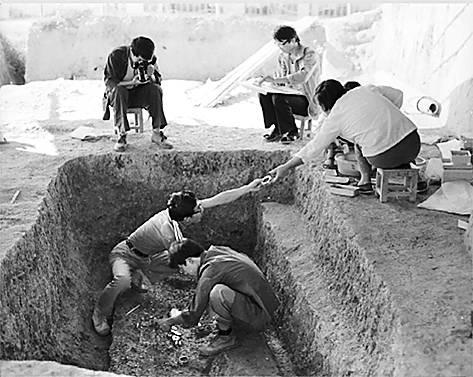

This immensely powerful figure was not lying there all alone. In fact, his burial pit is among 10 others arranged in two lines that make up what's known today as the Fanshan Cemetery. Collectively, the 11 tombs have yielded nearly 7,000 jade items, most of which were finely crafted.

The jade yue (axe), which shared the same tomb with the cong and the scepter. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

The jade yue (axe), which shared the same tomb with the cong and the scepter. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

If the pharaohs had chosen to cover themselves with gold, one of the biggest assets of ancient Egypt, then the Liangzhu rulers did so with jade, a substance that had endowed them with the same supreme power.

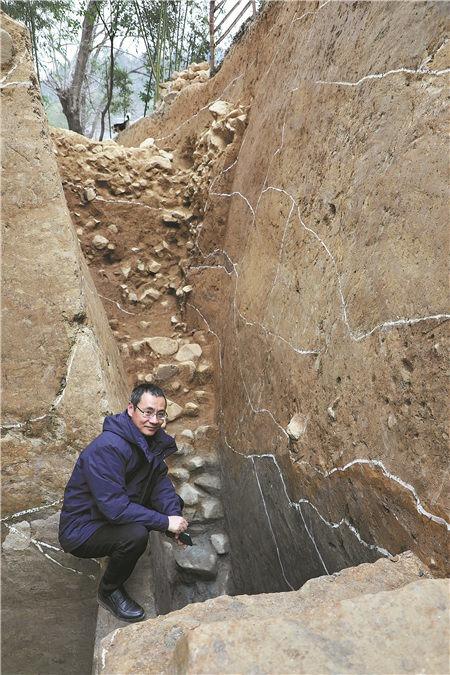

Equally interesting is the fact that this burial ground is merely a trench away from a palatial complex that lies to its southeast. Composed of three earth mounds piled on top of a rammed-earth platform measuring about 630 meters from east to west, and 450 meters from north to south, the whole structure is believed to have once sustained the weight of some monumental constructions.

"They were more likely to be temples of worship than residential palaces," says Wang.

The archaeologist became increasingly convinced of his judgment, as the true scale of the Liangzhu Ruins, including a walled city centered on the complex and a colossal water conservancy system affecting an area as vast as 100 million square meters, has been uncovered over the past 15 years.

Zhou Yun with the ivory scepter featuring 10 man-and-beast images across its surface. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Zhou Yun with the ivory scepter featuring 10 man-and-beast images across its surface. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

The building of a society

The amount of labor required for such a project challenges the imagination, especially given the rather primitive tools the Liangzhu people had at their disposal. They were, at least in part, motivated by the same thing that had committed the jade-carvers to their endeavors, says Wang, pointing to two tiered altar cemeteries that lie far outside the outer city walls.

Both were built in the very early stage of the Liangzhu civilization, before the Fanshan site and the palatial complex, and have turned out a sizable amount of ritual jade including cong bearing the aforementioned man-and-beast motif.

"A unified belief seems to have formed before the construction of the city and served as a major driving force. Those laid to eternal rest at Fanshan, given the amount of jade they possessed in the afterlife and the site's location, were very likely to be ones who made the decision to build Liangzhu as we know it today. They did so in the name of the divinities, with whom they communicated, aided by ritual jade items," Wang says.

An aerial view of the archaeological site for Liangzhu's palatial complex. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

An aerial view of the archaeological site for Liangzhu's palatial complex. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Few have studied the Fanshan jades as carefully as Fang Xiangming who, in 2001, spent more than six months recording each and every one of them through his drawings, which at one point were done with Fang wearing gloves so that his sweaty fingers wouldn't be in direct contact with the pieces. Today the director of the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Fang reminisces about that experience in Wang's oral history.

A major challenge was presented by the "king of all cong", whose maker, a master craftsman, managed to carve five fine lines within a width of 1 millimeter. "With the thinnest drawing pen I could find at the time, I couldn't do it, which meant that I couldn't draw it at a 1:1 ratio," the 56-year-old recalls.

The man-and-beast pattern has strained both of his eyes — in very much the same way it does to visitors at the Shanghai Museum — and his mind.

"The man's head is in the shape of a trapezoid. He's probably wearing a mask and, if he is, then chances are he's a Shamanic witch or chief priest," Fang says.

Jade huang with matching jade tubes. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Jade huang with matching jade tubes. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

"As for the beast, its enormous eye may have something to do with sun worship, or belong to an eagle or a feline. But its crouching position also hints at it being a pig. ... I wouldn't be surprised if this mythical creature is an amalgam of various animals — much like the dragon, Chinese civilization's arch emblem."

Although the motif appears on many other forms of Liangzhu jade, including crests and trident-shaped items, its combination with cong contains a significance that is unsurpassable, says Fang.

"Cong, in my view, embodies within its geometric form the Liangzhu people's view of the universe," he continues. "From top to bottom, the cylinder — if it can be called one — has a very slight taper. If you have the experience of standing in an open field surveying your surroundings, with an unobstructed view, you would know that the earth is a circle — or at least appears so to you — with its border defined by where it meets the heaven.

A map showing the location of Liangzhu and the region to its north, including the Yangtze River and Taihu Lake, that forms the territory of the Liangzhu civilization. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

A map showing the location of Liangzhu and the region to its north, including the Yangtze River and Taihu Lake, that forms the territory of the Liangzhu civilization. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

The heaven, of course, is also a circle, albeit a bigger one encompassing you."

Fang believes that, while the hollow cavity inside creates a channel between heaven and earth, the outer, rectangular prism, with its four vertical faces and eight corners, stands for si mian ba fang, meaning all directions.

"This is acute observation articulated through abstraction," reflects Fang, who considers Liangzhu civilization one centered around, if not solely defined by, its jade culture.

Jade awl-shaped objects. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Jade awl-shaped objects. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

"Why? Because it holds the key to issues of cultural identity, political organization and social development. Through jade, the people of Liangzhu have conveyed their ideas about nature, beauty, power, religion and ultimately, themselves."

The Shanghai exhibition includes a wide array of jade animals from the period, including birds, tortoises, a fish and a cicada. The first three may have something to do with animal worship, augury and even the food staple of the Liangzhu people, who literally lived on marshland. The last one, which may or may not be coincidence, later became a crucial part of ancient China's funerary culture and a symbol of virtue.

According to Fang, an arch-shaped jade artifact known as huang has almost only turned up in the tombs of females, and is sometimes accompanied by small jade tubes, which served as the "string" to which huang was attached to form a necklace. Jade spinning wheels and loom fittings, understandably, had also been unearthed exclusively from the burial ground of Liangzhu women.

Likewise, a type of trident-shaped jade is typically found in men's tombs, sometimes with a set of jade awl-shaped objects. They are believed to be headdresses worn together, with the latter spread out like sunrays.

Fang Xiangming, director of the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Fang Xiangming, director of the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

However, jade played its irreplaceable role in Liangzhu society not by being gender-specific, but class-specific. While elite members of society enjoyed their afterlife surrounded by exquisite jade treasures, the burial chambers of their lesser mortals were mostly full of pottery, with the occasional, roughly-made jade awls or tubes.

Through adopting what scholars have dubbed "differential burials" or more generally, "a hierarchical system of jade usage", the Liangzhu people, while reaching the apex of prehistoric Chinese jadeware production, also took their stratified society across the threshold of early statehood.

"At the time, metal mining had yet to develop in this area. As a result, nephrite, or jade as we call it, became the most coveted material whose ownership was indicative of power and status," says Zhou Yun, curator of the Shanghai exhibition. "That's why it was prized over other, more accessible minerals, such as agate."

Titled The Proof of Early China, the exhibition seeks to examine Liangzhu's status as a civilization and its position in the larger concept of Chinese civilization.

During Fanshan Cemetery excavation in 1986, Wang Mingda reaching out to his colleague from a burial pit with a jade bracelet in hand. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

During Fanshan Cemetery excavation in 1986, Wang Mingda reaching out to his colleague from a burial pit with a jade bracelet in hand. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

"At one time, based on their study of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, archaeologists had considered writing (and record-keeping by extension), metallurgy and city-building as the three hallmarks of a civilization. But what about the Maya civilization, which didn't develop metallurgy until very late, in around AD 800, or the Harappan civilization and the Inca civilization?" says Zhou, noting that the latter two, not unlike Liangzhu, didn't develop a writing system. (The Harappan script, also known as the Indus script, is now widely considered by the academic world as constituting a corpus of symbols instead of a written language.)

"Instead, what bound them together as 'civilizations', and set them apart from the various 'cultures' that predated them, are a set of prominent traits including arts and architecture, cities and governments, stratification of society, coupled with a complex division of labor, all of which had characterized the existence of Liangzhu," she continues.

A natural conclusion

In September 2017, the scale of Liangzhu jadeware production was partly revealed with the excavation of the Zhongchuming site, located about 25 kilometers northeast of Liangzhu city. Within the 1-million-square-meter area, archaeologists discovered living quarters, burial grounds, jade workshops and dumping pits. In the workshops and pits, many raw jade materials, as well as finished, semifinished and defective products have been found.

"It's clear that the several villages in that area had collectively taken up jadeware production as a profession and a means of living, thanks to a huge demand," says Wang. "The area's crisscrossing waterways may have provided transportation for the raw materials to be delivered, and finished products to be exported."

Wang Ningyuan, lead archaeologist working at the Liangzhu site. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

Wang Ningyuan, lead archaeologist working at the Liangzhu site. (GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY)

In the meantime, people who spent countless hours rubbing down a piece of raw jade, or carving intricate lines across its surface, must also be fed. Those working in the paddy fields must have produced enough extra crops to make sure the artisans and craftsmen could concentrate on their work. Behind the jadeware production was a division of labor reflective of Liangzhu society at large.

During excavations conducted between 2015 and 2017, along an ancient river course running right along the eastern fringe of the palatial complex, archaeologists unearthed not only discarded jade materials and products, but also giant logs and human skulls. For those in the know, they tell a story of Liangzhu, one about the forming of a belief system and the making of a city, before all that glory was lost to the repeated invasion of floodwater coming from the east where the land met the sea.

That record of marine transgression, fatal to rice crops that couldn't stand the saline water, was kept in the multiple thin layers of silt, which today covers large areas of the Liangzhu site and the regions to its east. On top of that was the relentless rain brought on by the monsoon season and the typhoons, slashing the land and crippling Liangzhu's flood-control system. These are considered by some researchers as the leading cause for Liangzhu's demise around 2300 BC. Such destructive natural occurrences were coupled, perhaps not surprisingly, with eruptions of violence, even close to the heart of the city.

Yet, there's another narrative thread, one that is spun around a jade story.

"Liangzhu people chose to build their city in a basin surrounded on three sides (north, west and south) by the mountains, with only one side open to the alluvial plains and the funnel-shaped Hangzhou Bay to its east," says Zhou. "The mountains are believed to have contained deposits of jade, whose depletion toward the end of the Liangzhu civilization may have been seen as an omen."

According to Fang, although cong pieces are still found in late phase of Liangzhu tombs, sometimes even in larger numbers within a single pit, they were often made either with low-quality jade or a replacement, such as serpentine.

Having tried very hard to read between the carved lines, Fang believes that he has made inroads into the minds of those who created the man-and-beast image with unmistakable intention, clarity and uniformity.

"Look at the way it replicates itself within one single item," he says, pointing to an ivory scepter showcased at the Shanghai exhibition, across the surface of which 10 of the motif are arranged as if engaged in a heavenward spiral.

"It could be a sun god, which many cultures from East to West have depicted as simultaneously having multiple incarnations, thanks to the deity's daily ride across the sky," Fang continues.

"But they are more likely to be ancestral deities — the fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers from whom the men and women of Liangzhu descended, and with whom they would eventually join."