An exhibition examines the best and worst of times of a bygone British era, Lin Qi reports.

Echoes From the Age of Steam, an exhibition of Victorian-era British art being held at the galleries of the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Echoes From the Age of Steam, an exhibition of Victorian-era British art being held at the galleries of the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Charles Dickens opens A Tale of Two Cities with the luminary lines, "It was the best of times; it was the worst of times." This statement from the historical drama set against the backdrop of the French Revolution has remained so resonant that it's often been quoted in myriad contexts since its publication.

And its sentiment embodies the spirit of Echoes From the Age of Steam, an ongoing exhibition of Victorian-era British art at the galleries of the National Centre for the Performing Arts on Beijing's Chang'an Avenue that runs through March 25.

One part depicts the vibrant art scene and social life during the period when the Industrial Revolution propelled Britain's rise as a powerful empire and economy under Queen Victoria's rule.

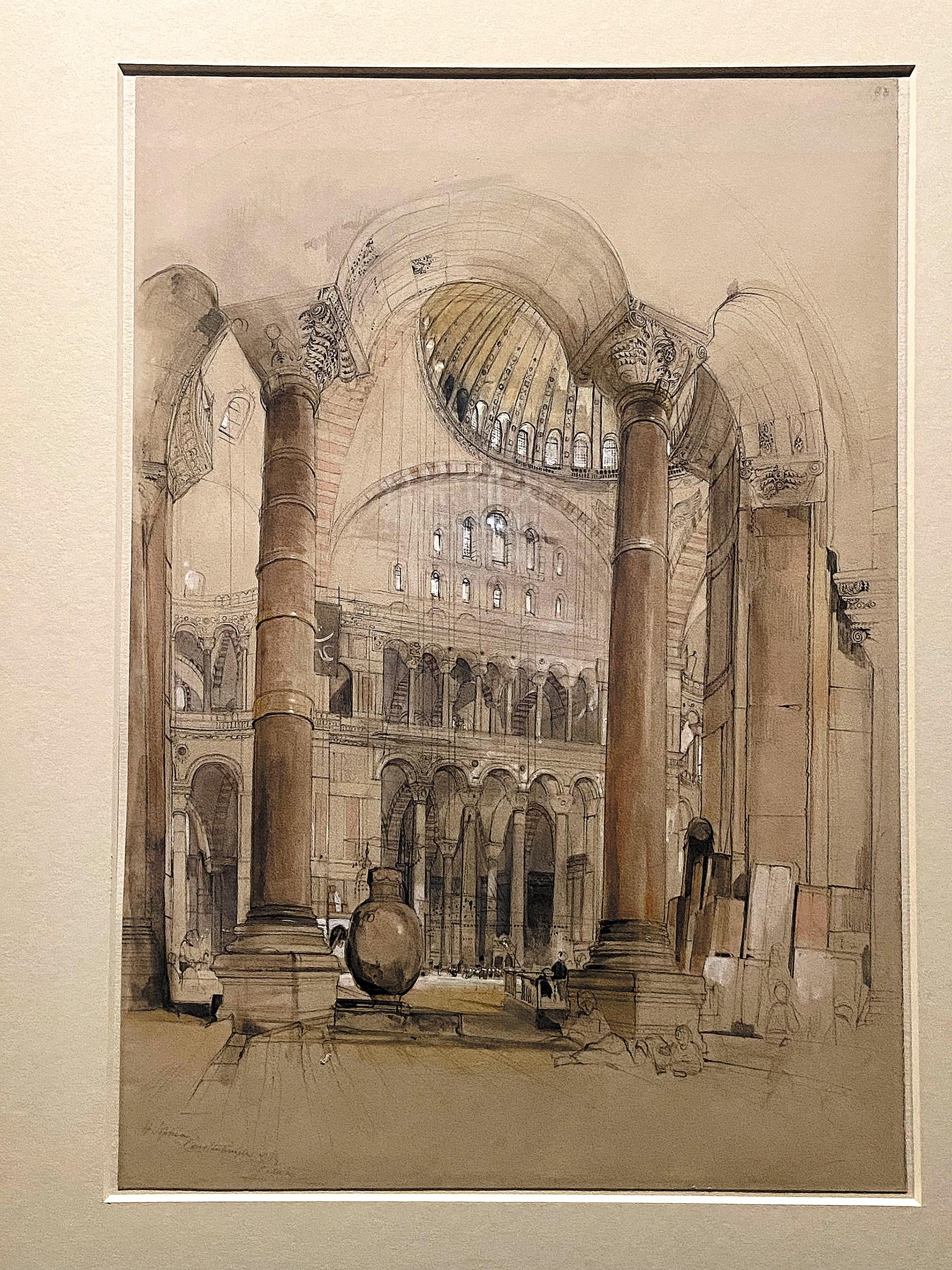

Interior of Santa Sophia, Constantinople, by John Frederick Lewis, is one of the exhibits. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Interior of Santa Sophia, Constantinople, by John Frederick Lewis, is one of the exhibits. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In another section, artists from that time also reveal the other side of a prosperous state: the plight of the working class, money worship, growing disparity between the rich and the poor, pollution in cities and environmental deterioration.

On show are oil paintings, watercolors, drawings and sculptures that introduce British artists' development throughout the 19th century, as they created diverse works and initiated several larger art movements with lasting influence.

The works on display are from the several venues of the National Museums Liverpool, including the Walker Art Gallery, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Sudley House and World Museum, says Sandra Penketh, executive director of galleries and collections management at National Museums Liverpool.

Two 19th-century ceramic vases made in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

Two 19th-century ceramic vases made in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

Natural inspiration

The shift from agriculture to industrialization brought dramatic changes to every aspect of British society.

In terms of fine arts, a group of homegrown artists, art buyers and patrons emerged, and exhibitions were staged to bring more cultural experiences and better education to more people, says Li Mo, an exhibition curator at the National Centre for the Performing Arts.

Of the many artists who gained acclaim during this period, Joseph Mallord William Turner helped to elevate the landscape painting to an eminence that rivaled previously predominant motifs. That's why his painting, The Wreck Buoy, opens the exhibition.

An 1849 remake of a previous version exemplifies Turner's innovative use of color in a highly expressive manner and his noted mastery through turbulent marine scenes. Art critic John Ruskin once described this piece as, "the last oil he painted before his noble hand forgot its cunning".

The Wreck Buoy by Joseph Mallord William Turner. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Wreck Buoy by Joseph Mallord William Turner. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Turner's name is closely associated with British landscape painting, and he is known as one of the most influential British artists of all time.

In February 2020, the Bank of England issued a 20-pound note featuring a self-portrait Turner created around 1799 that's housed in Tate galleries. The note also shows his quote: "Light is therefore colour."

Turner accentuated, with strong emotions, the sublimity of nature so much that the sometimes violent scenes in his work evoke a sense of fear. Other painters preferred to hail the greatness of nature in a simple and tender way, with an attention to detail.

"In this way, they addressed city dwellers' yearning for the peaceful countryside — a land of lush greenery, free of the problems generated by industrialization," says Li.

A 18th-century ceramic vase made in Jingdezhen. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

A 18th-century ceramic vase made in Jingdezhen. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

Examples shown at the exhibition include Forest Glade With Deer: The King of the Forest, a collaboration between Thomas Creswick and Richard Ansdell, and Flying the Kite: A Windy Day, a landscape piece by David Cox. It's said that a viewer of this work by Cox once told the artist of his propensity for depicting winds: "There is always a breeze in your pictures! I declare I shall take cold and must put on my shawl."

Such an enthusiasm for nature reflects the pursuit of truth through aesthetics.

Li, the curator, says this inspired several art movements that originated in Britain — the influence of which later expanded to the European continent and further around the world — such as the Arts and Crafts movement, the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood and aestheticism.

An Italian Child (Tuscan Girl Plaiting Straw), by William Holman Hunt. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

An Italian Child (Tuscan Girl Plaiting Straw), by William Holman Hunt. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Demographic features

The growth of the middle — and working-class populations during this period meant they increasingly served as the subjects of art — beforehand, most works depicted religious figures, fairy-tale characters, royalty and aristocracy.

Paintings on show portray idealized lifestyles, and the underlying social rules and moral values, promoted by the middle class — a house in the suburbs; a quiet and virtuous wife; and adorable and well-behaved children.

Women in these affluent families are often portrayed as enjoying leisure, while leaving domestic chores and child care to servants. But they were legally and financially dependent on men.

Yes or No? (right), a work by Charles West Cope. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

Yes or No? (right), a work by Charles West Cope. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

A telling example of this on show is George Goodwin Kilburne's Poor Relations.

It shows a narrative scene in which a woman expresses resignation as she holds her face with one hand while her unhappy looking husband gives cash to her father following the death of her sister's husband.

The situation was, indeed, dire for the poor. The working class' struggles are depicted not only through paintings but also such arts and crafts as a necklace on display that's made using gold and human hair. Back then, women who lived in poverty often sold their hair.

Flower Makers, by Samuel Melton Fisher. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

Flower Makers, by Samuel Melton Fisher. (LIN QI / CHINA DAILY)

Such jewelry was worn by wealthy elites, who decorated their living spaces with crafts from around the world, sometimes including Chinese porcelain. The exhibition shows patterned porcelain dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries from Jingdezhen in today's Jiangxi province — arguably the material's leading production center then.

"These works show not only the cultural diversity of 19th-century Britain but also many other aspects of society and the lives led by different classes that offer audiences a panoramic view of the Victorian age," Li says.

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn