The furor surrounding the sudden emergence of a “prince” from Dubai planning to set up family offices in Hong Kong, followed by his subsequent disappearance, has stunned the city. What can the SAR learn from it? Oasis Hu has been following the events that unfolded about a year ago.

The unfolding events read like a fiction thriller.

The sequel to the melodrama involving the “Dubai Prince” who was purportedly going to supply a megabucks boost to Hong Kong’s bid to become a global family office destination may soon be revealed. Will he return bearing the $500 million he had announced he would use to set up a family office in the city before he vanished without a trace?

It all began in May last year when a man known as Sheikh Ali Al Maktoum registered a website for his private office, introducing himself as “an emblematic figure hailing from the ruling family of Dubai”. His photo showed him as a typical Middle Eastern figure with a long white ghutra, thick eyelashes and deep-set eyes.

READ MORE: New center targets region's green future

The “distinguished royal family member” subsequently made frequent high-profile appearances in Hong Kong. Apparently sealing his personality and business intentions, he visited Hong Kong Cyberport in December last year and gave interviews to Bloomberg in mid-March, in which he was referred to as the “Dubai ruler’s nephew” who planned to fork out $500 million creating a family office in the special administrative region. On March 26, the “prince” signed an agreement with Hang Seng University and became an honorary professor. The following day, he spoke at the prestigious Wealth for Good in Hong Kong Summit and was welcomed by Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu.

But soon, matters made a rapid about-turn. Not long after the summit, “Dubai Prince” Ali abruptly announced his plans had been put on the back burner till late May due to “urgent matters”, and he would return to Hong Kong later. The “Dubai Prince”, who had been making headlines in the city for months, disappeared over the far horizon.

Hong Kong media then started casting doubts on the identity of the “prince”, digging into his background. It was revealed he had another persona — a singer named Alira who debuted in the Philippines in 2020. But, in February last year, Alira had hastily ended his singing career, with his official website, YouTube channel, and Instagram account being deleted. A few months later, he reappeared on the web as “Sheikh Ali” — a tycoon, a leader of a private office and a figure from the ruling family of Dubai.

According to various sources, he merely belonged to a “distant branch” of the royal family. Some members of his private office were questioned, including executive director William Tien, who had previously run a cryptocurrency trading platform that received a warning from the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Eleanor Mak, vice-chairperson of “Dubai Prince” Ali’s family office, had past associations with a company that was labeled by China’s Supreme People’s Court as having engaged in dishonest acts.

The HKSAR government came under criticism for having failed to vet Ali’s identity, although some observers said the government had done nothing wrong. Others saw the episode as a joke, while still others called it an international scam.

In response, Lee said on April 17 that family offices can provide substantial economic benefits to host cities, and Hong Kong has been striving to invite operators of family offices to do business in the city, irrespective of their backgrounds, as long as their capital is legitimate. The SAR will try to strike a balance between risks and benefits, he said.

Whether Ali will eventually return is anybody’s guess. But one thing is certain — Hong Kong has a lot to reflect on as to what has happened.

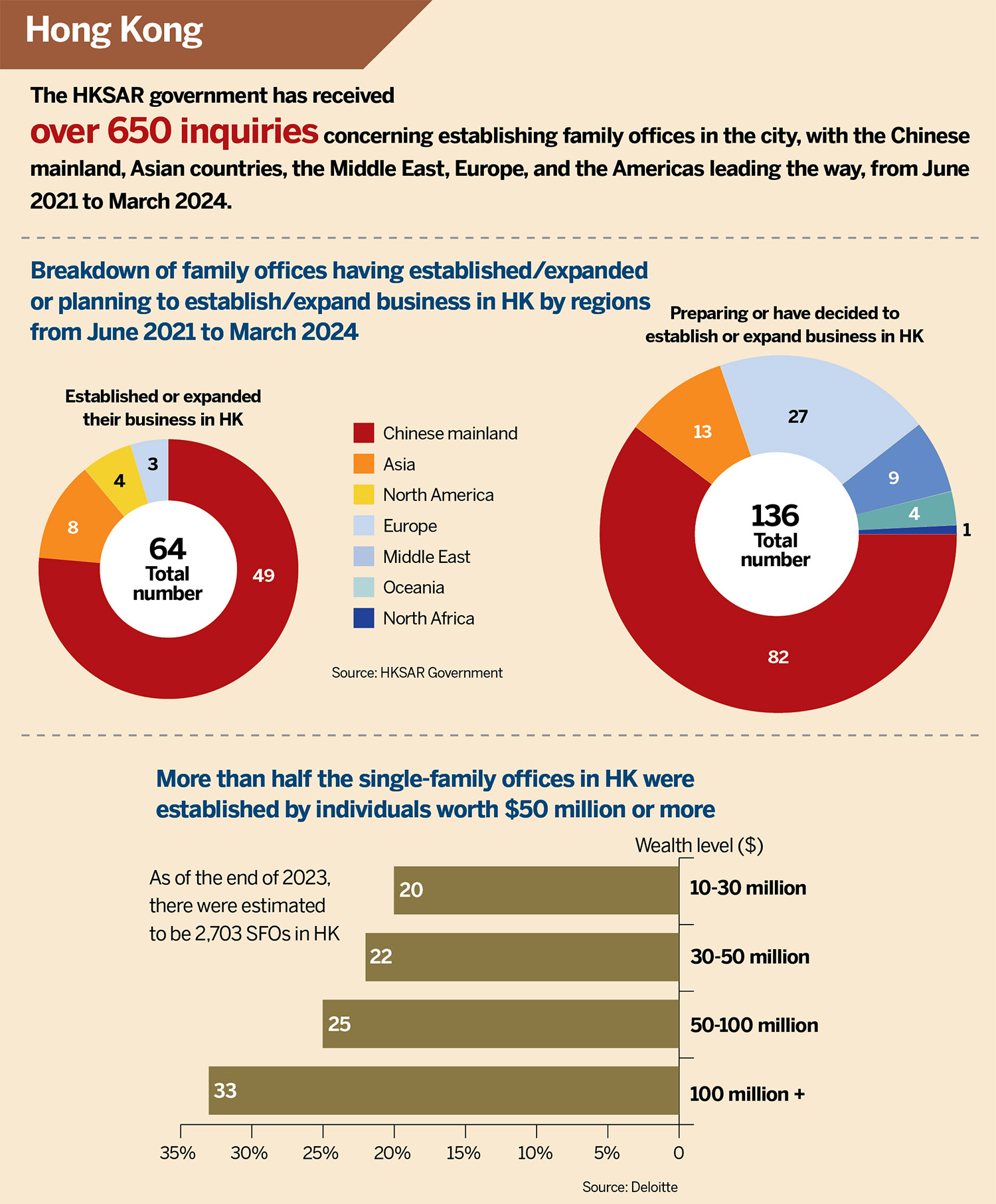

Vigorous promotion

According to Shawn Sun Yangsheng — a lawyer and co-founder of Schaeffer Family Office (Asia) Co Ltd — the controversy surrounding the “Dubai Prince” floated against the backdrop of the SAR government’s active promotion of family offices in recent years. In his maiden Policy Address in October 2022, Lee set a target of attracting at least 200 family offices to establish or expand their operations in the city by late the following year. To back up this objective, the government issued its Policy Statement on Developing Family Office Businesses in March last year, offering tax exemptions, streamlined licensing, talent development, service team support, as well as a host of preferential policies to foster the growth of family offices. In May the same year, the Legislative Council passed a bill offering concessionary taxes for single-family offices.

Chen Dong — vice-chairman of the Chinese Financial Association of Hong Kong and president of Right Time Asset Management Co Ltd, explains that in the broadest sense, a family office can be understood as an organization that helps wealthy families to manage their businesses. These activities can be categorized into three main areas — financial investments, non-investment but money-related matters, such as charity work, taxes, foreign exchange and credit, as well as non-financial matters like emigration, travel, marriages and funerals. However, the SAR government’s definition of a family office is narrower — it must be a company that provides only financial management services, excluding all other matters like immigration, educational and legal issues.

Chen explains that family offices are commonly categorized into two types — single-family offices and joint-family offices. A single-family office offers services exclusively to one particular family — exactly the same type that “Dubai Prince” Ali had registered. In Hong Kong, for a single-family office to be deemed eligible to operate, the total value of assets managed must be at least HK$240 million ($30.76 million). In contrast, a joint-family office is designed to serve multiple families.

Family office and family trust are distinct concepts. Broadly speaking, a family office focuses on investment and profits, whereas a family trust deals with ownership and distribution of wealth, explains Chen. Both concepts are not mutually exclusive and often work in tandem. High-net-worth individuals often set up both to make their wealth management more standardized, professionalized, institutionalized and enduring.

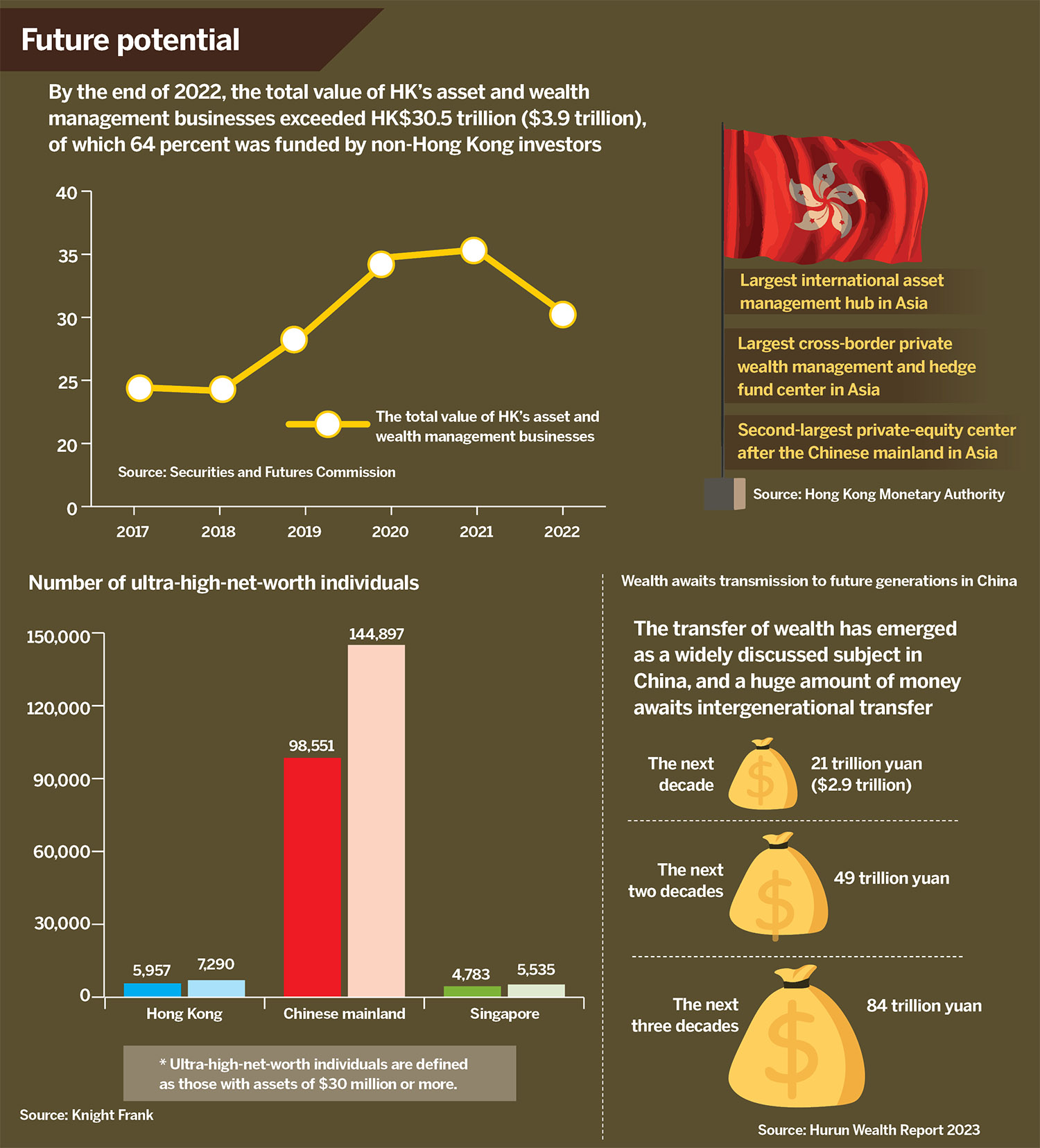

In Chen’s view, it’s reasonable for the government to promote family offices as they straddle the twin realms of asset administration and financial management, serving as “the pearl in the crown of the global wealth management industry”. Besides, HK$240 million — the money needed to set up a single-family office — is equivalent to the amount needed to be raised by eight investment immigration applicants. The SAR government introduced the new Capital Investment Entrant Scheme this year, requiring an applicant to invest at least HK$30 million in eligible categories.

More significantly, tycoons who establish family offices in Hong Kong often migrate to the city, boosting high-end consumption. They often require an array of professional services, including accountancy, private banking, education, estate planning and concierge services, creating many high-value jobs.

Sun believes the government’s support for family offices can create enduring connections between Hong Kong and wealthy individuals worldwide, fostering a comprehensive and long-term related industrial chain. “Promoting family offices is not only beneficial to Hong Kong’s financial industry, but also its overall economy,” Sun said.

Less than perfect policy

Sun says the government shouldn’t be blamed for the “Dubai Prince” saga. According to the law enacted in Hong Kong last year, there’s no requirement for a licensing process to establish a single-family office. Applicants are only required to prepare the necessary documents for registering a corporate entity. During the tax season in April, they must apply to the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) for a tax exemption. At this stage, the IRD will assess whether that entity qualifies for tax-exempt status as a family office, based on the eligibility criteria.

In other words, during the registration phase, the government’s examination of a single-family office primarily focuses on its compliance with the registration requirements for a company. This process is similar to that of any general asset management company, almost without background checks. “To put it simply, just for the process of registering the family office, the government does not need to conduct a background check on the ‘Dubai Prince’ at all,” says Sun. “Actually, such an approach aligns with Hong Kong’s identity as an international financial center known for its freedom and minimal control, which can be appealing to many outside investors.”

But Chen argues that while the government complies with the existing process, it does not necessarily mean that the process itself is perfect. Under the new law, the process of creating a family office in Hong Kong as “a post-review system” could lead to loose management in the early stages. Many individuals applying to run a family office in Hong Kong are usually in the dark about how to start, he says.

Also, it’s strange that the final determination of qualification for family offices is made by the IRD rather than a financial department. As a result, if the IRD does not have specialized statistics, the exact number of family offices in Hong Kong will never be clear. “The overall process is somewhat disorderly,” says Chen.

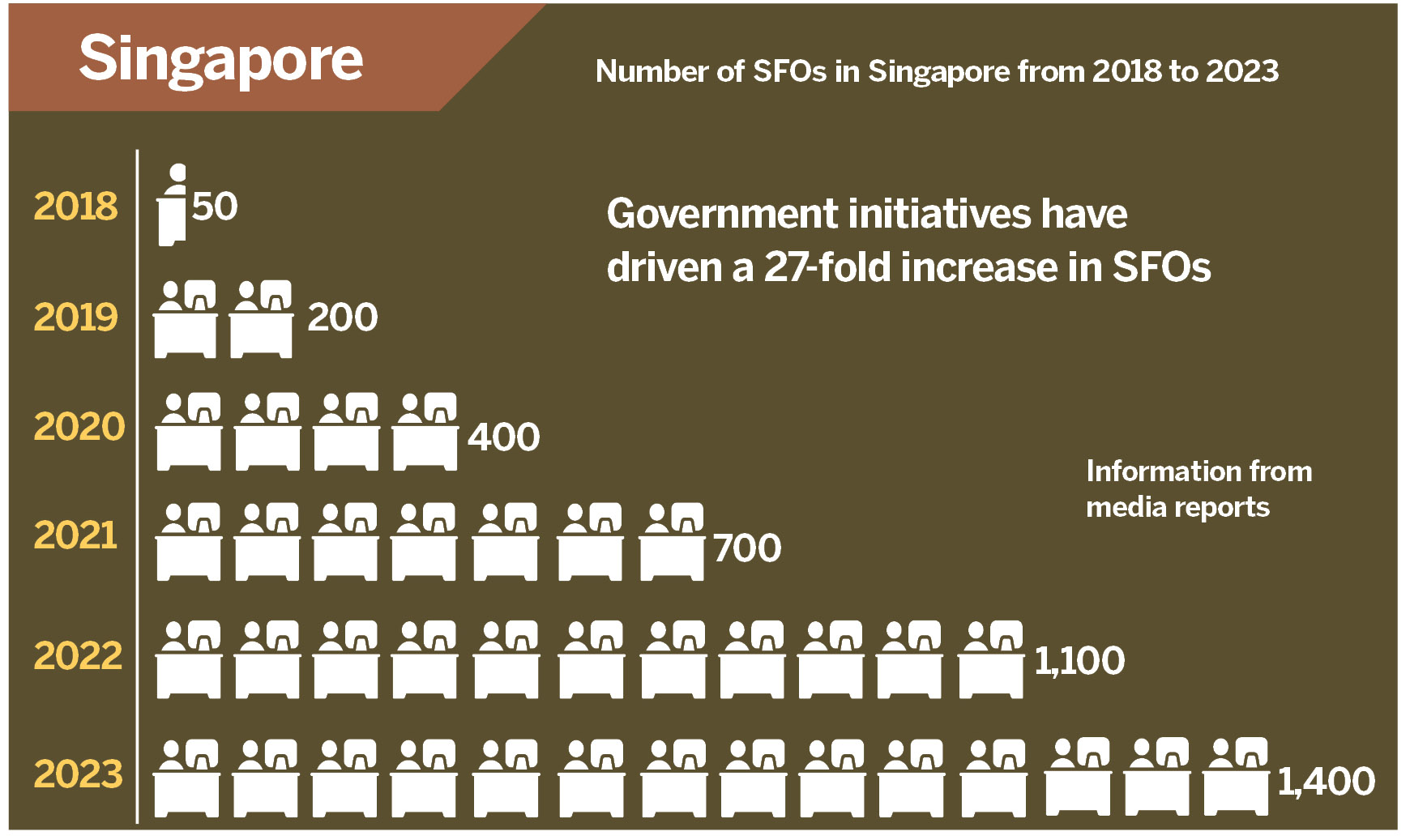

In contrast, the Chinese mainland and Singapore follow a “prior approval process”, which is more logical and reasonable, says Chen. In Singapore, applicants must deposit the funds with a bank first before applying to the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), undergoing interviews and obtaining final approval from the MAS before the family office can be formally established.

The entire process is transparent and managed by a separate department. The statistics on the number of family offices are clear. The “Dubai Prince” controversy would be unlikely to occur in Singapore as the money transfer is a prerequisite for calling it a family office, Chen explains. He suggests that the SAR government adopt Singapore’s practice and introduce a pre-qualification step for the creation of family offices.

There has been a global trend of significant development and growth in family offices across several regions in recent years.

Singapore saw a significant surge in the number of family offices after implementing favorable policies in 2018 — rising from 50 to 1,400 by the end of last year, marking a 27-fold increase. However, in Hong Kong, while there are about 2,700 family offices, many are older establishments, and data on new additions since the introduction of preferential policies has yet to be disclosed. There are indeed many areas that need to be improved on in terms of family offices, suggests Chen. For example, Hong Kong can lower the threshold for setting up a single-family office.

Singapore’s minimum asset management requirement for a single-family office is S$10 million ($7.38 million), which needs to be raised to S$20 million within two years (about HK$115 million) — significantly lower than Hong Kong’s requirement of HK$240 million.

Hong Kong can broaden its tax exemption policy to include joint-family offices instead of limiting it to only single-family offices, Chen suggests. Hong Kong can also take the cue from the Lion City by introducing a preferential policy granting Hong Kong identity status to applicants of family offices.

Reflection

Sun views the “Dubai Prince” issue as “not a very significant thing”, saying that in business, it’s common for people to express investment interest but, ultimately, not following through, or there’s a significant disparity between the proposed fund amount and the actual investment made. Even if “Dubai Prince” Ali fails to show up again with the funds, it’s understandable, he says.

However, the government should not reveal the matter during the investment invitation stage and give it large-scale publicity. “We can see Hong Kong is eager to prove itself,” he says, adding that the city does not need to be excessively anxious.

Despite recent economic fluctuations in both Hong Kong and on the mainland, the SAR’s global financial center remains resilient, says Sun. Hong Kong has many inherent strengths, including professional services, a skilled workforce, a favorable tax regime, a robust legal system and its enhanced integration with the mainland.

“While the inflow of capital is beyond our control, the ability to excel in Hong Kong’s own endeavors can be managed. Instead of relying on excessive public relations, the city should prioritize self-improvement by maintaining market rules and maximizing its strengths,” says Sun.

Danny Cheung Ho-wing, chair of a family office with 17 years’ experience in global asset allocation, says the government should have verified the identities of guests before deciding on the appropriate level of officials who meet them when organizing major events. The presence of government representatives, particularly the chief executive, can be perceived as an official endorsement. If the “Dubai Prince” incident was indeed a scam, it could harm the city’s reputation.

The head of a local multi-family office consulting group, who preferred to remain anonymous, told China Daily that while the family-office concept has been practiced in the West for a century, it’s still in its infancy in Asia. Absorbing and localizing Western practices in Asia would take time and it’s normal to encounter challenges during the process.

Recent international attention to the matter is proof that Hong Kong’s family office industry is entering a phase of rapid growth. As the world’s focus shifts to Hong Kong, the city needs to be more cautious while continuing to move forward at full speed. It must pay meticulous attention to operational details, ensuring it can earn the trust of investors and the scrutiny of the global community. The government should learn from the global experience, step up efforts to conduct more research on the industry and enhance more communication with industrial professionals, the consulting group chief said.

ALSO READ: Luring the affluent with a tinge of cultural dynamics

Fung Ho-keung, chief executive officer of the Hong Kong Policy Research Institute, says the fact that the identity of “Dubai Prince Ali” had not been questioned at various levels of the Hong Kong authorities — from university to the media, event organizers and the government — proved that the city lacks general knowledge of or expertise in matters pertaining to the Middle East.

Hong Kong has traditionally focused on its dealings with Western countries, and it has been relatively easy for the city to obtain information about investors from these regions, such as the United States, the United Kingdom or Canada. However, the same level of familiarity does not extend to the Middle East.

The availability of authoritative Middle Eastern think tanks in Hong Kong is limited, as are centers for Middle Eastern studies at local universities. The Chinese University of Hong Kong has the Centre for the Study of Islamic Culture, but it focuses on cultural aspects rather than international relations, politics and the economy of the Middle East, Fung notes.

Given the complex geopolitical conflicts, diverse backgrounds and intricate Islamic laws in the Middle East, Hong Kong should build up its understanding of the region, and hire experts to establish a specialized think tank or expand research courses on the Middle East at local universities, he suggests.

Contact the writer at oasishu@chinadailyhk.com