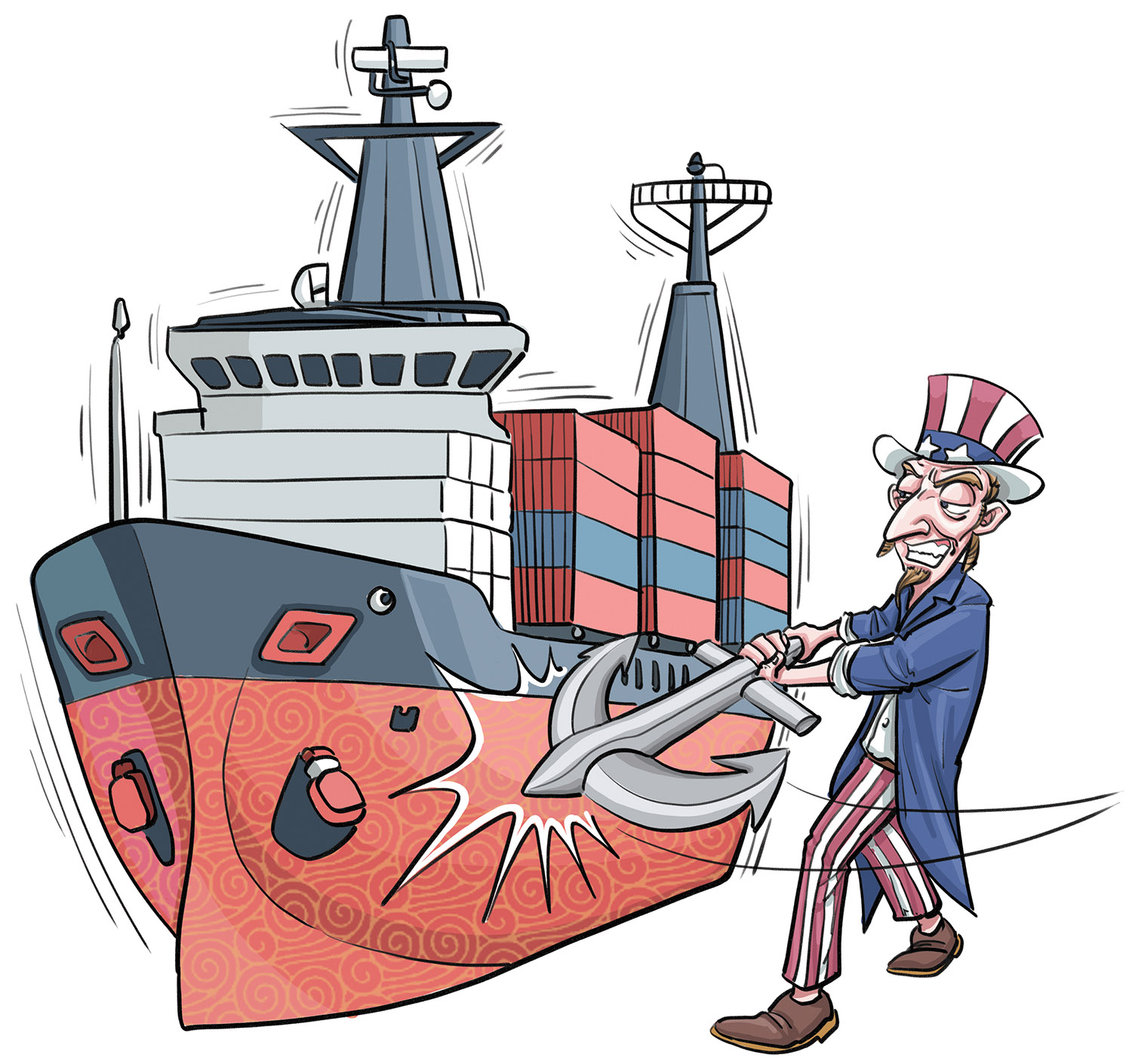

Washington must abandon abuse of ‘Section 301’ as a tool to curb key Chinese industries

The Joe Biden administration on May 14 announced punitive tariffs on Chinese-made electric vehicles (EVs), solar photovoltaic panels, EV batteries, steel, aluminum, and medical equipment. Following a four-year review under Section 301 of the US Trade Act of 1974, the tariff on EVs imported from China will be raised from 27.5 percent to 102.5 percent.

Washington is supposed to use Section 301 to take “corrective” action against trade practices it deems unfair or those that violate international trade rules.

READ MORE: US tariff hikes on Chinese products seen an 'unfortunate policy shift'

But now it is using Section 301 as a weapon to check the development of China’s industries. In fact, China needs to prepare for another round of investigations under Section 301 targeting its maritime trade, and logistics and shipbuilding sectors, which were initiated in April in response to a petition filed by five leading US national labor unions on March 12.

The US was the world’s largest shipbuilding nation during World War II, and until the 1970s it had the world’s largest shipbuilding industry. But thanks to Japan’s fast resurgence, the US had to cede the top position to the East Asian country by the 1980s. In the late 1990s, the Republic of Korea (ROK) rose as a formidable latecomer and grabbed a big share of the global market, which resulted in the shrinking of the US shipbuilding industry. At that time, China’s shipbuilding industry was very small and had nothing to do with the decline of the US as a shipbuilding nation.

The Chinese shipbuilding industry’s ascent began in earnest in the 2010s. By the end of last year, China accounted for 50.2 percent of all merchant tonnage produced globally, pushing the ROK and Japan into second and third place. The US, on the other hand, accounted for less than 1 percent of the total tonnage produced globally in 2022.

In the past 80 years, the global shipbuilding leadership has passed from the US and the United Kingdom to Japan, to the ROK, and to China. This is an economic trend and has nothing to do with China’s trade policies.

In the meantime, the US had been focusing on a number of new industries including information and communications technology, big data, artificial intelligence, supercomputing, biotechnology, and, like shipbuilding during World War II, accounted for half of the world’s semiconductor output.

Similarly, China used to be the world’s largest maker of shoes and apparel, but its share in both sectors has been declining over the past 10 years. This is another example of the industrial gradient transfer phenomenon.

US labor unions have all the right to voice their concern and find the real reasons behind the US shipbuilding industry’s decline, and the US Trade Representative Office is obligated to help them. But instead of doing that, the USTR is using Section 301 to target China’s industries.

The US Trade Act of 1974 is a law that has no jurisdiction in other countries. Hence, the US and China, both being World Trade Organization members, should refer their trade disputes to the WTO dispute settlement mechanism.

Clause 23 of the WTO dispute settlement rules states that no member has the right to declare that another member has violated a rule — only the WTO dispute settlement mechanism can do that. Members, however, have the right to submit complaints to the mechanism, seeking redressal.

ALSO READ: Biden unwisely dons the mantle of 'tariff man'

In August 2018, China lodged a complaint with the dispute settlement mechanism against the US for imposing extra tariffs on Chinese imports based on a Section 301 investigation. In September 2020, the mechanism ruled that the US tariffs violated WTO rules and were thus illegal.

Claiming the US’ subsidy policies discriminate against foreign automakers, undermine global efforts to adopt EVs, and distort fair competition, China filed a formal complaint against the US Inflation Reduction Act in March.

Hopefully, the US will adopt the right approach to the issue, and the USTR will drop Section 301 investigation, and move the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism to look into the Chinese shipbuilding issue. And since the WTO mechanism allows the disputing sides to enter into consultation, China and the US should amicably settle the issue.

The author is a senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.