Exhibition demonstrates long-lasting charm of a particular shade in history, Wang Kaihao reports in Nanjing.

It's green. It's also blue.

Originating from nature, this color of vitality has not only left its mark on the various perspectives of Chinese people's daily lives throughout history, but it has also been associated with poetic reminiscences for many generations.

The color cyan, known as qing in Chinese, continues to comfort and inspire people today.

We hope to present the aesthetic beauty of this unique Chinese color concept.

Zhang Xuemeng, exhibition curator

An exhibition in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu province, Cyan, The Exceptional Chinese Color, unfolds a fascinating epic on this colorful legend through 180 cultural relics on loan from across the nation.

READ MORE: Firing up the next generation

Opened in the city's Oriental Metropolitan Museum, the exhibition was co-launched by Art Exhibitions China and the Nanjing Museum Administration and will run until October.

"We hope to present the aesthetic beauty of this unique Chinese color concept," Zhang Xuemeng, a curator of the event from Art Exhibitions China, explains. "The theme choice is made also due to the rich and broad interpretations of 'cyan' in traditional Chinese culture. We aim to delve deep into the cultural spirit it embodies.

"This color is reflected in various aspects of traditional Chinese cultural life: clothing, food, housing, transportation, leisure activities and more," she adds. "This diversity in cultural representation naturally leads to a variety of exhibit types."

Jade, porcelain, turquoise, glassware, clothes, paintings and other varieties of objects spanning millennia, the gallery resembles an idyllic mountain setting or a rustling bamboo forest.

Real bamboo is used to decorate the gallery and a giant showcase is designed in the shape of rolling mountains. Zhang Lei, a co-curator of the exhibition from the Oriental Metropolitan Museum, came up with the idea to create a mesmerizing atmosphere for visitors to approach, witness and appreciate ancient literati's feelings by replicating the natural settings from yesteryear.

"In China, different colors are given various ceremonial meanings," Zhang Lei says. "In ancient Chinese text, the term qing was also used to describe a wide spectrum of colors including blue, green and sometimes gray. This one word has a rich connotation."

Cyan is one of "five colors" that was used by ancient Chinese people to describe everything in the world, based on yin-yang and the related five elements theory.

In Rites of Zhou, a fundamental ancient Chinese classic on organizational theory, this color was also used to refer to the East.

It was almost as if cyan was predestined to best represent the eastern aesthetics in the following centuries.

Stories of precious stones

To design such a comprehensive exhibition, it is natural to first credit jade when reviewing the lasting legacies of cyan in Chinese culture.

From arc-shaped huang or disc-like bi of the Neolithic period (10,000 to 4,000 years ago), the 3,000-odd-year ritual cong, a straight tube with a circular bore and square outer, to exquisite decorations from the Warring States Period (475-221 BC), jade demonstrated people's understanding of the color in early history, but was not based solely on aesthetics.

"Jade artifacts served as key symbols in ceremonies and sacrificial rituals," Tan Ping, director of Art Exhibitions China, says. "The exhibits are witnesses to the unified ceremonial system of a centralized authority, reflecting the unity of Chinese civilization."

Once seen as a crucial indicator of national governance, jade later played a key role in aristocratic burial customs during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) as a bridge to connect with the afterworld.

Following the 3rd century, jade was widely worn as a daily accessory by various social classes in China.

"Ancient Chinese referred to jade items to worship heaven," Zhang Lei explains.

"They also often used this cultural icon to describe men with virtue.

"From the very beginning of our civilization, jade has been seen as something precious," she continues. "People tend to have some special affection for its color, its soft green revealing elegance. The color also represents everything growing in nature."

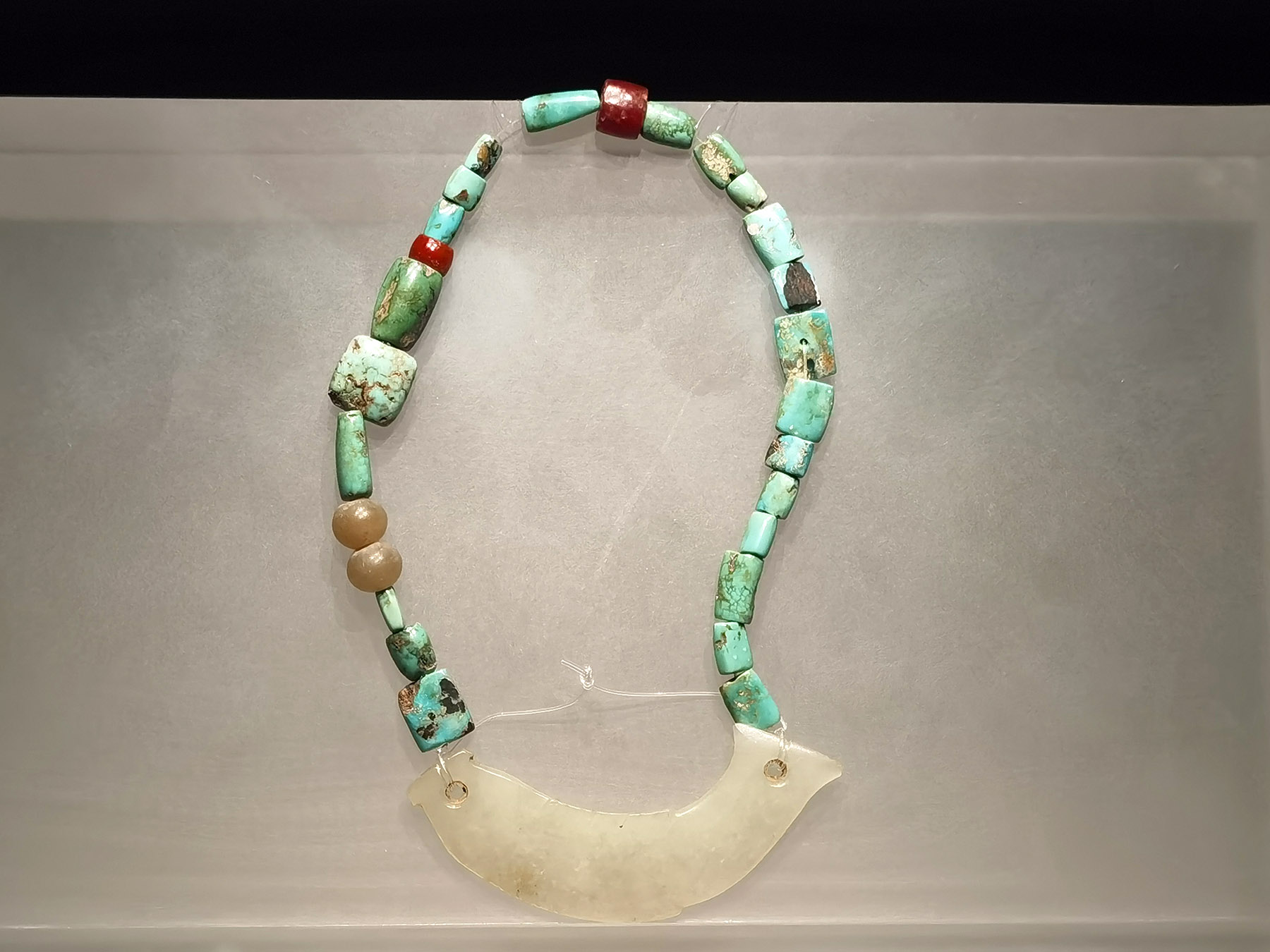

Compared with this dominating role of jade, the significance of turquoise in ancient China seems to have been overshadowed. However, like many other key hubs of ancient civilizations, China also had a long tradition to admire such a precious stone, as the exhibition shows.

A bronze handle inlaid with turquoise from the Western Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century-771 BC) is such an example.

Back then, turquoise was often used as decorations on bronze weapons, ceremonial items, or settings on horses and chariots. An exhibited necklace of turquoise from the same period also reveals Chinese people's admiration for cyan.

Exquisite ceramics

Ancient poets dedicated numerous stanzas to admire cyan. A rich and descriptive collection of words were used to describe its subtle variations, like canglang (rippling waves), xizi (West Lake beauty), zhuyue (bamboo moon), or qianshancui (verdant mountains), as Zhang Lei notes.

Ceramics probably stand out as a perfect and long-lasting way to fully interpret this exquisite group of colors.

Celadon, most notably produced in Longquan kilns in Zhejiang province dating back more than 1,700 years, showcased its green charm, particularly by the literati.

Changsha wares from Hunan province, during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), were famed for their vivid reflection of natural hues.

The basic tone of celadon was dotted with green adornments. People then often marked paintings and poems on the wares, reflecting a prosperous era of literature.

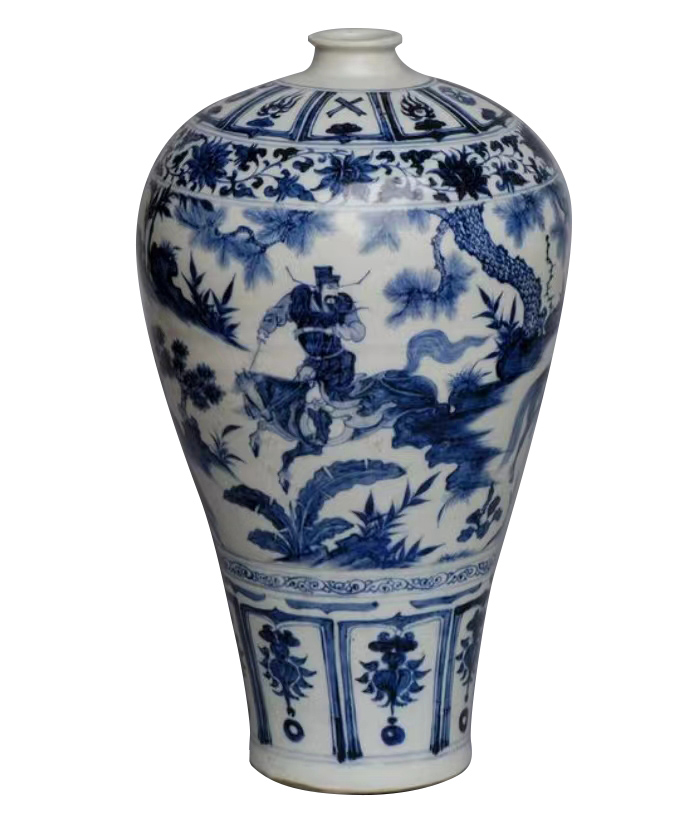

Blue-and-white porcelain from the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), though produced via imported dye, evolved into a signature example of made-in-China products.

In one highlighted exhibit, a Yuan blue-and-white porcelain displays the work of artisans who drew a vivid scene of a famous play.

This scene depicts Xiao He, a statesman from the Han Dynasty, chasing after Han Xin under the moon and persuading this disappointed general to change his mind and come back to serve the Han.

"The decorative patterns of these porcelains show fashion and popular topics during different times," she says.

"Other than admiring their outstanding techniques, we can also feel the warmth of life from these relics."

Longquan products, blue-and-white porcelain and Changsha wares all sailed along the Maritime Silk Road centuries ago, Tan adds.

"From ancient times to the present, the exchange and mutual influence among civilizations have always been the main theme of historical development," he says. "It vividly reflects the inherent 'harmony' in the genes of the Chinese nation."

A resonating space

Putting this exhibition in the Oriental Metropolitan Museum is not the result of coincidence.

The museum focuses on history between the 3rd to 6th centuries when Nanjing was the capital of six dynasties that ruled the southern part of China and rose as a metropolitan city with a powerful influence. Nanjing is thus often dubbed as the "ancient capital of six dynasties". The museum regularly displays 1,200 related relics, among which celadon is a pillar of its inventory.

"People then had a tendency to admire the color of cyan," Zhang Lei says. "It shows a pursuit for harmony between humans and nature."

She further explains: "While North China was shaken by continuous wars, a large group of literati were exiled to the south. The unstable social environment made them listen to their 'inner world' more often and highlighted the importance of individual feelings and psychological relief."

As the exhibition shows, forests, plants and natural landscapes, which were used as backdrops or adornments in paintings, became main features in artworks during this nature-worshipping era. Blue-and-green landscape paintings later became a key genre in traditional Chinese art.

Naturally, cyan, reminding visitors of the Six Dynasties period, can easily resonate with modern urban dwellers who also look for inner peace amid their fast-paced life, Zhang Lei points out.

Tan from Art Exhibitions China sees the exhibition as a chance to explore an alternative combining resources of middle- and small-sized museums.

"Compared with those large museums, many such smaller venues are less noticed, but they are deeply rooted in local cultures and closer to people's daily life," he says.

"Presentations of their collections in thematic design can thus provide better cultural service."

According to Song Yan, deputy director of the Nanjing Museum Administration, about 60 percent of visitors to the Oriental Metropolitan Museum are aged between 10 and 35.

"That means, as operators of modern museums, we have to approach history in a fresh and comfortable way," says Song, also a deputy to the 14th National People's Congress.

ALSO READ: Depths of understanding

"After a few years of experiencing the booming scenario of Chinese museums, today's visitors have well-nurtured taste. They will not be satisfied with just checking out a new museum and seeing treasures. They seek a deeper understanding through immersive experiences to feel the cultural ethos of the past times.

"This process is essential for art education for the public," she says. "In this way, people can also fall in love with history and breed closer emotional ties with the city they live in."

Song has long promoted her idea of ushering museums into people's regular lifestyles by building a "museum without boundaries".

In the Oriental Metropolitan Museum, people pass through bamboo groves in the galleries. They also stop in front of the huge French window on the third floor to appreciate the soothing summertime scene: The verdant city skyline of Nanjing spreads toward the horizon. Boundaries of time and space seem to blur at that moment.

By the exit of the cyan-themed exhibition, a wall is full of comments left by visitors. Many of them cite famous poems on color throughout history, but some people write their own.

"Mystic shade of cyan, elusive yet alluring," a visitor writes. "It's refreshing, and makes me approach."

Probably, for the exhibition curators admiring the color of life, this "growing" wall is the fruit they harvest.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn