Resident ensemble brings China's history to life using duplicate instruments and classic dances, Chen Nan reports in Zhengzhou.

It's a quarter to 11 in the morning on a regular Tuesday as crowds pack into the Henan Museum in Zhengzhou, the capital city of Central China's Henan province. The museum, founded in 1927, is home to about 170,000 artifacts and sets and is particularly famous for its prehistoric pieces, bronzes from Shang and Zhou (c. 16th century-256 BC) dynasties, ceramics and jadeware.

A corner on the first floor of the museum houses a concert hall, which has diverse audiences ranging from parents with young children to the elderly queuing outside.

READ MORE: Drawing inspiration from ancient artifacts

"What are we going to see? A pianist? Or dancing?" a boy asked his mother. "No, it will be very different," the young mother replies.

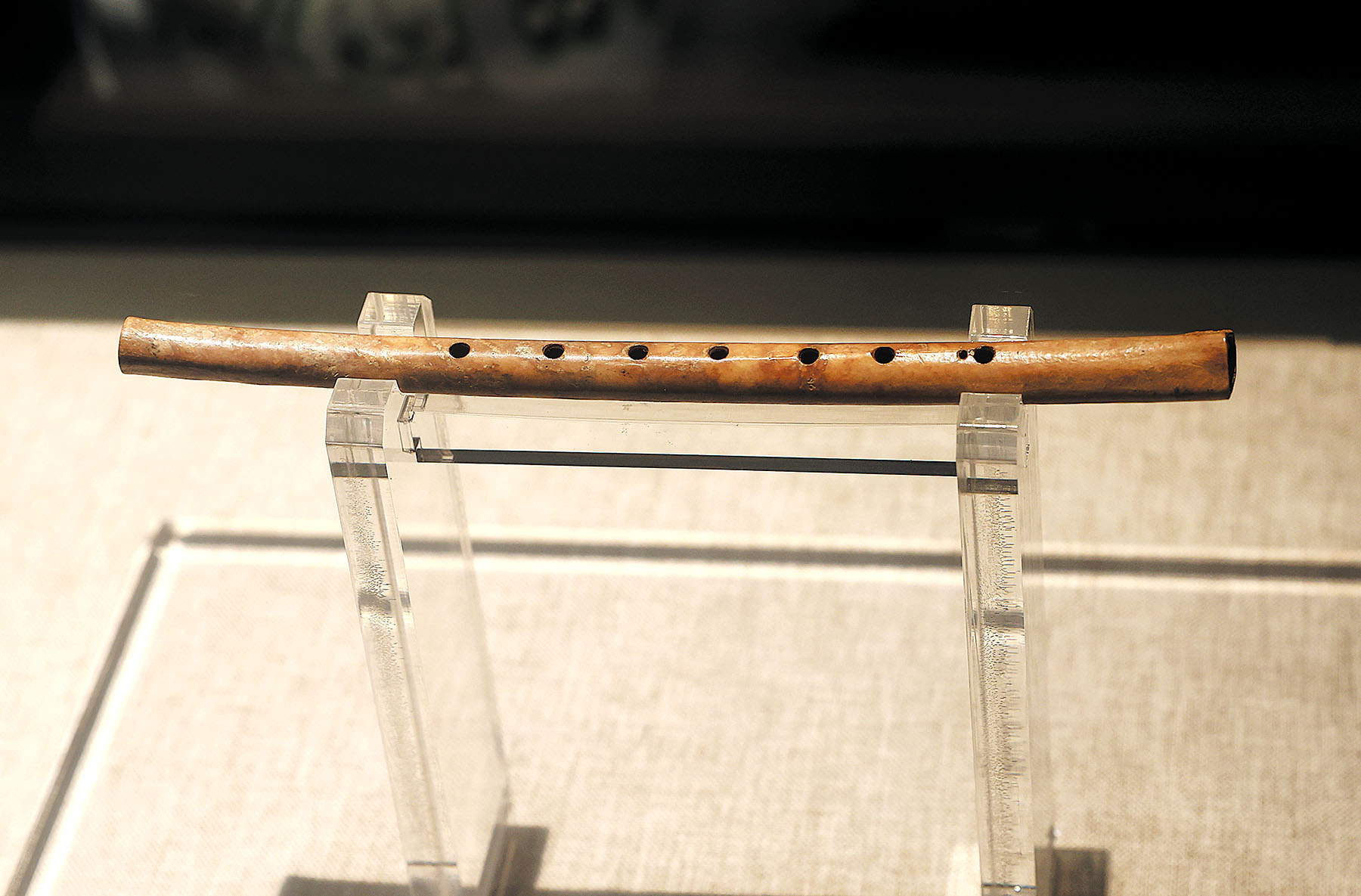

The bone flute

At 11 am sharp, the show begins with Yan Wentao dressed in costume from the Neolithic period (10,000 to 4,000 years ago), or New Stone Age, blowing a bone flute behind an LED transparent screen, with the screen flashing images of forest and mountains.

Yan is a member of the Huaxia Ancient Music Orchestra, the resident ensemble of Henan Museum founded in 2000, which currently has 30 members. Huaxia is a romantic Chinese word referring to China.

To revive the country's ancient musical traditions, the orchestra plays about 10 types of replicas of ancient musical instruments housed in Henan Museum, which come alive in an acoustic feast that transports listeners to a long-lost era.

With the introduction of the show's host, audiences learn that the bone flute is a replica of a key exhibit at Henan Museum of the Jiahu bone flute (gudi), from about 8,700 years ago.

Excavated at the Jiahu Site, Wuyang county, Henan province in 1987, the 23.1-centimeter-long flute was made from the wing bone of a bird from the crane family. It is shaped like a long pipe with seven holes drilled in a straight line down one side. It is the earliest musical instrument unearthed in the country that still produces sounds.

"The flute has a clear five-octave range, a possible basis for a seven-note scale. The discovery of the Jiahu bone flute has rewritten a portion of China's music history," the host says.

"Every time I perform the bone flute onstage, I feel I'm taking the audience on a trip back 8,700 years by bringing its timeless melodies back to life. The haunting melodies once reverberated across ancient China, echoing the sentiments of our early ancestors," says Yan, 28, who learned to play the bamboo flute as a child and joined the Huaxia Ancient Music Orchestra after he graduated from a music training program launched by Zhengzhou University and the Henan Vocational Institute of Arts in 2018.

A year after joining the orchestra, Yan started to produce bone flutes, which are replicas of the Jiahu bone flute.

"When I was a child, I was drawn to the sound of the bamboo flute, which gives me goosebumps. I planned on joining a traditional Chinese orchestra or becoming a music teacher. Now, I am doing more than that. I not only play the flute but also make instruments based on cultural relics and historical documents, reviving the melodic treasures of the past, which has introduced me to a whole new world," says Yan.

According to Yan, the Jiahu bone flute replicas use the bones of large birds, such as eagles, that died of natural causes. The most challenging part of making the flute is measuring the positions of the holes and drilling the embouchure.

"Drilling each hole and adjusting its size for the desired pitch is key to producing the flute. Tuning requires patience and experimentation," Yan says. "There are no textbooks to teach us how to play these instruments and they demand different techniques. We had to learn by trial and error."

"The restoration and replication of ancient musical instruments is not merely an academic exercise but a profound cultural endeavor. It's about celebrating the wisdom of our ancestors," Yan adds.

Sounds come alive

According to Huo Kun, the director of the Huaxia Ancient Music Orchestra, the orchestra concerts sold out quickly during weekends and public holidays.

"We give two shows each day except Mondays when the museum is closed. During weekends, public holidays and summer and winter vacations, we put on extra shows to meet the audience demand," says Huo.

Classically trained tenor Huo joined the Huaxia Ancient Music Orchestra in 2002 after graduating from Zhengzhou University. In 2015, he won the position of director of the orchestra.

He notes that when he first joined the orchestra, there were only 10 musicians and its repertoire was limited. During the past decade, the orchestra's mission has gone beyond mere performance — it is a journey to re-create and reinterpret the musical legacy of ancient China.

It has revived over 30 ancient Chinese musical instruments, such as a set of bianzhong, or bronze chime bells, consisting of a set of bells of varying sizes that produce different sounds when struck; xun, an oval flute-like clay instrument; and the bone panpipe, an ancient vertically blown braided wind instrument.

"In the quiet context of museums, these instruments are often displayed but once they could be played, the instruments come alive, reminding us of the richness and depth of China's musical heritage," says Huo, emphasizing the orchestra's role in bringing these relics to life. "These ancient harmonies are not just echoes of history but vibrant expressions that connect us to our cultural roots in a profound and unforgettable way."

The orchestra has also arranged over 150 music pieces by using the instruments they made. Beyond its traditional repertoire, the orchestra ventured into performing contemporary and pop songs, appealing to younger audiences while preserving its ancient sounds. The pieces, including adaptations of songs from the Harry Potter franchise and Chinese pop song Lonely Warrior, or Gu Yong Zhe, usually get the warmest feedback from the audience, according to Huo.

This fusion of old and new not only attracts a broader demographic but also revitalizes interest in traditional instruments among the youth.

Huo mentions that he had never expected that his life would be so deeply connected with archaeology, which is a crucial part of the orchestra's development.

Archaeological delights

He vividly recalls when he went to Xinyang Museum along with other members of the orchestra to do research in 2017, there he saw a set of bianzhong that was unearthed in 1957 in Xinyang, Henan province. With a history dating back to the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), the nine bells, with the smallest as tall as 13.9 cm and the largest as tall as 40.1 cm, still shine a golden color.

"I was amazed by the bells. When I struck them, the beautiful sound took me back to ancient China instantly. I had many questions, such as who played those bells back then? Who did they play for? Beyond mere entertainment, they offer profound insights into the human experience, traversing time and space," Huo says.

Besides preserving ancient sounds, the orchestra also revives the costumes and there are traditional Chinese dances during performances — all based on research.

Wang Jing, 35, who learned classical Chinese dance as a child, joined the orchestra in 2011 as a dancer and choreographer.

"I visited Henan Museum with my friends in 2010 and saw the orchestra performance, which intrigued me. I contacted them after watching the show and applied for a job," recalls Wang, who graduated from Zhengzhou University with a major in musical performance.

"I started training in classical Chinese dance when I was nine and my training was all about imitating the movements of ancient Chinese beauties, which only exist in books, museums and paintings. After joining the orchestra, I can bring those beauties alive onstage, which may inspire and resonate with audiences today," says Wang.

ALSO READ: Tuning in to Beijing's charms

Along with her colleagues, Wang visited museums across China, which allowed her to learn and get inspired by cultural relics such as pottery dancing figurines.

She also joins the orchestra's training program for children, which offers them a platform to learn how to play traditional Chinese musical instruments and dance.

"All of our choreographic pieces are rooted in cultural relics and historical documents, just like the orchestra plays replicas of ancient instruments. Each note played on these instruments and each dance step is a testament to the enduring beauty of Chinese culture," says Wang.

Contact the writer at chennan@chinadaily.com.cn