The world in 2022 reached its most ambitious deal ever to halt the destruction of nature by the decade's end.

Two years later, countries are already behind in meeting their goals.

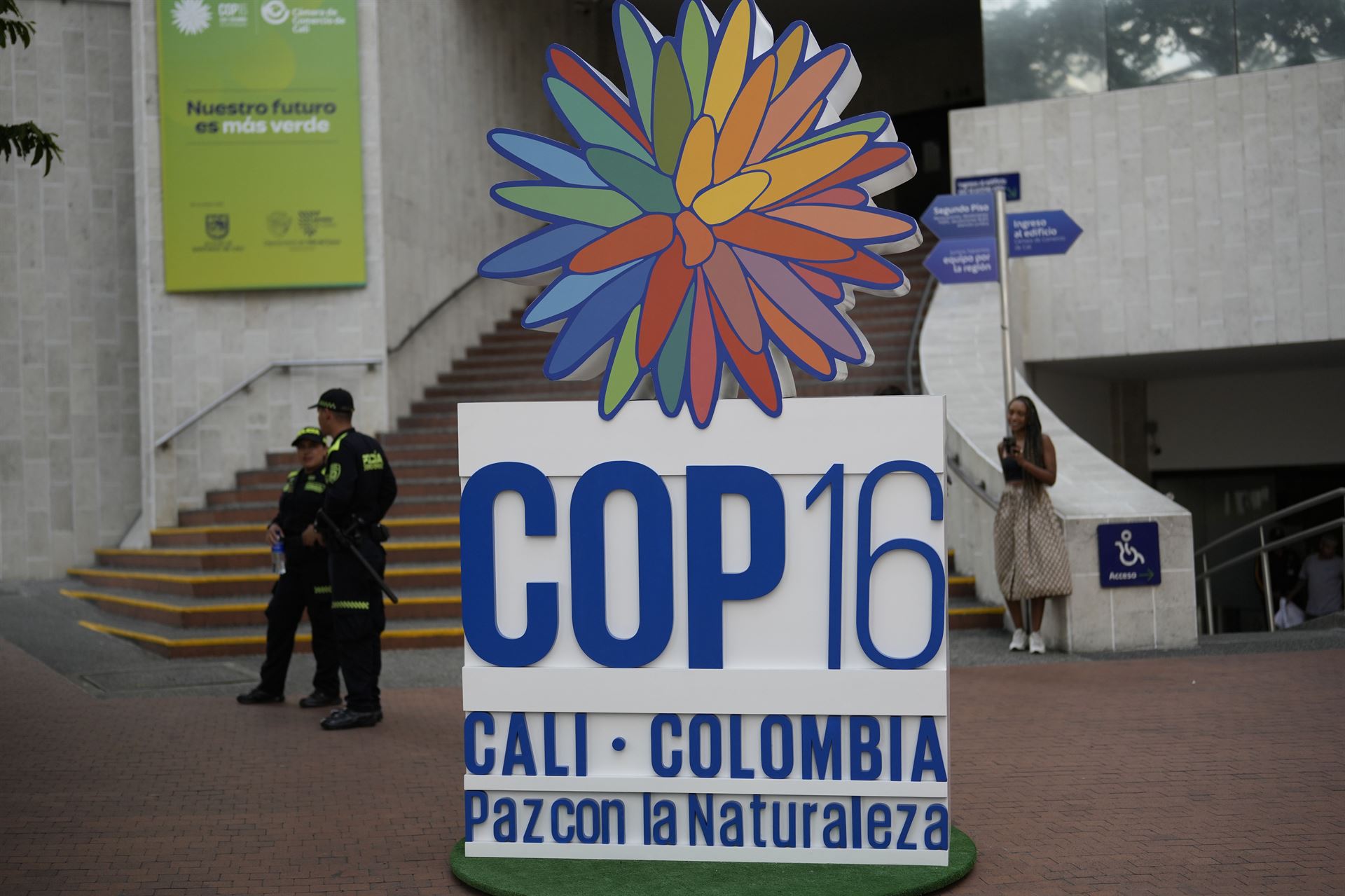

As nearly 200 nations meet on Monday for a two-week UN biodiversity summit, COP16, in Cali, Colombia, they will be under pressure to prove their support for the goals laid out in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework agreement.

A top concern for countries and companies is how to pay for conservation, with the COP16 talks aiming to develop new initiatives that could generate revenues for nature.

"We have a problem here," said Gavin Edwards, director of the nonprofit Nature Positive.

"COP16 is an opportunity to re-energize and remind everybody of their commitments two years ago and start to course correct if we're going to get anywhere close to 2030 targets being achieved," Edwards said.

ALSO READ: Watchdog: Some G20 regulators overlooking risks linked to nature loss

The rate of nature destruction through activities like logging or overfishing has not let up, while governments miss deadlines on their biodiversity action plans and funding for conservation is billions of dollars away from meeting a 2025 goal.

The summit in Colombia, marking the 16th meeting of nations that signed the original 1992 Convention on Biodiversity, is set to be the largest biodiversity summit to date, with some 23,000 delegates registered to participate as well as a large exhibition area open to the public.

Richer nations have been quicker to file with many European nations, Australia, Japan, China, South Korea and Canada having filed their plans.

The United States attends the talks but never ratified the Convention on Biodiversity, so is not obligated to submit a plan.

Another 73 countries as of Friday had opted to only file a less ambitious submission that sets out their national targets, without details of how they would be achieved.

With so few plans filed, experts will likely struggle to gauge progress in meeting the agreement's hallmark "30 by 30" goal of preserving 30 percent of the land and sea by 2030.

Colombia's Environment Minister Susana Muhamad, who also serves as COP16's president, said that while the summit needs to assess the plans submitted so far, it must also look to address why so many others are late.

"It could be that the funds are not enough, for example, to be able to produce the plans," Muhamad told Reuters. Countries with newly elected governments also may still be getting up to speed, she said.

READ MORE: Lifeline

Poorer countries have had a harder time finding the funding and expertise needed to develop national biodiversity plans, said the World Wide Fund for Nature's (WWF) advocacy chief Bernadette Fischler Hooper.

Money for nature

Beyond getting countries to commit to conservation policies and plans, a top priority for the COP16 summit is finding new funding sources for poorer nations to meet nature goals.

During the COP15 talks in 2022, negotiators set a goal for $20 billion annually by 2025 to help developing countries on biodiversity.

That is not much more than the $15.4 billion per year that was already flowing for nature by 2022, according to OECD data published in September. While that makes the 2025 target more achievable, it also means the target could have been more ambitious.

"If you're just looking at new money that's been announced since (COP15) to implement this framework, it's pretty thin," said Brian O'Donnell of the Campaign for Nature advocacy group.

READ MORE: 'Boiling world' should jointly fight climate change

Because there is a two-year lag in the data, countries will not learn how much is being spent on nature this year until after the goal kicks in.

The world moved quickly after the COP15 deal to set up a new Global Biodiversity Framework Fund within months.

The fund was envisioned as one of the world's principle instruments to pay for conservation, aiming to raise billions in dollars.

But few countries have since contributed, with only $238 million collected so far, according to data compiled by Campaign for Nature.

Muhamad said that, amid the financing conversation and policy reviews, negotiators need to keep their sights on the real-world nature crisis unfolding.

She has also urged nations to consider their plans for tackling climate change as part of their biodiversity agenda, given that the two are interlinked. For example, global warming has heated the oceans to unprecedented levels, with the world experiencing its fourth mass bleaching event this year.

"The final indicator really is what's the reality of biodiversity loss," she said. "We are not better off now than we were two years ago."