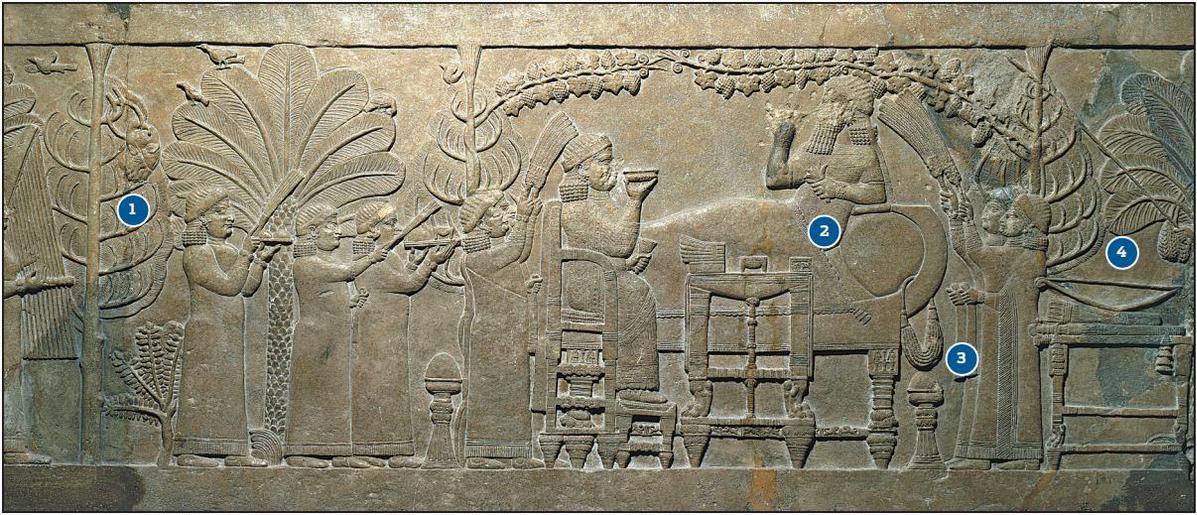

A king of ancient Assyria was relaxing with his queen in what's believed to be the queen's garden under the cool canopy of grape vines. Raising their cups to their lips, the king and queen — one reclined on a couch while the other sat on a throne — appeared to congratulate each other. For what? One possible answer will send shivers down the spines of visitors to the Suzhou Museum in Suzhou city, East China's Jiangsu province, where a major exhibition, I Am Ashurbanipal: King of Assyria, sheds a rare light onto the lesser-known civilization of Assyria.

The one man around whom the exhibition's narrative has been spun is Ashurbanipal (669-631 BC), whose 38-year rule marked the pinnacle of Assyria's territory expansion. In Nineveh, the Assyrian capital in modern-day Mosul, Iraq, the king built a magnificent palace known as the North Palace. He decorated it with wall after wall of sculptural reliefs recounting his life on and off the battleground, including the aforementioned garden scene, on view at the Suzhou Museum through video footage.

"For those in the know, the scene is more a reminder of than a respite from Ashurbanipal's relentless battles, which helped to win Nineveh the name 'the city of blood'," says Zhang Fan, the exhibition's project manager. He points to a multistranded necklace hanging from the king's couch and a group of weapons including a sheathed sword and bow piled on a table.

"The necklace, of Egyptian style, was likely a trophy from Ashurbanipal's campaigns in Egypt. The weapons were probably of the same nature — proof of the king's victories in Babylonia and Elam — the latter being an ancient country in southwestern Iran and historically renowned for its soldiers' archery skills," Zhang says.

Yet the most brutal reminder comes in the form of a severed human head hanging on a ring from the upper branches of a pine tree on the left side of the picture. Scholars believe it probably belonged to the Elamite king Teumman, who was defeated at the Battle of Til-Tuba in 653 BC. Keeping all this in mind, it wouldn't come as a surprise if the royal couple were toasting each other for the mayhem their troops had instigated against disobedient neighbors.

"In terms of storytelling, the reliefs were to the Assyrians what painted pottery was to the ancient Greeks. That's why we tried to borrow as many stone reliefs as possible from our partner, the British Museum, which the exhibits are from," says Zhang.

The height of an empire

The exhibition constitutes the final chapter of a three-part ancient civilization series highlighting the enviable collection of the British Museum. The previous two, focusing on ancient Roman and Greek civilizations, were held consecutively by the Suzhou Museum from September 2021.

"While all three were curated by the British side, we've paired them with an exhibition of our own that covers a corresponding period," says Zhang. "The Assyrian empire was at the height of its power during the first half of the first millennium BC, while China's Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 BC) was founded. We mounted an exhibition on the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, which saw China divided into different vassal states, all under the authority of a central ruler."

That authority was gradually eroded in the following centuries as the states fought with one another for survival. Iron weaponry was developed, and chariot warriors became an increasingly vital component of a powerful army which also included infantry and cavalry soldiers. "This mirrors what was happening with the Assyrian army, which derived its invincibility largely from the fearsome chariot warfare it conducted," says Zhang.

"In both ancient China and Assyria, the chariot component of the army was often associated with elite soldiers who received special training and were members of nobility. That's mainly because chariots were expensive to maintain and operate and therefore were the exclusive domain of the social elite," he adds.

"It's also worth noting that Assyrians most likely had learned aspects of chariot-making and chariot warfare from the Hittites, an ancient Indo-European people whom the Assyrians came into contact with through both war and cultural exchanges between the 15th and 13th centuries BC."

The Hittites used spoked wheels on their chariots, which appeared in China around 1300 BC during the late Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC).

Aided by his mighty troops, Ashurbanipal subjugated and terrorized neighboring countries, continuing a tradition long started by his ancestor kings including his grandfather Sennacherib and his father Esarhaddon, who handpicked his younger son Ashurbanipal to be his successor. To appease his resentful older son Shamash-shumu-ukin, Esarhaddon placed him on the throne of Babylonia, which at the time was a vassal state to Assyria.

This effort to make "equal brothers" was doomed. Shamash-shumuukin eventually rebelled in 652 BC against his younger brother after forming a broad coalition that included the kingdom of Elam.

Ashurbanipal responded with overwhelming force. In 648 BC, Babylon, the capital city of Babylonia, fell after a prolonged siege. Shamash-shumu-ukin met his end, the details of which remain unclear today. Ashurbanipal went on to avenge his brother's supporters, launching military campaigns to Elam which culminated in the destruction of two Elamite cities — Susa and Hamanu — in 647 BC.

Meeting their fate

The Suzhou exhibition displays a stone frieze originally from the North Palace of Nineveh that depicts the Assyrian siege of Hamanu. While the attacking Assyrian soldiers scaled the ladder leading to the top of a battlement defended by Elamite archers, the Elamites plunged to their deaths, their corpses floating in the moat below the city wall. If the Assyrian account is to be believed, Teumman, the Elamite king, was captured and killed by Assyrian soldiers, his head sent to Ashurbanipal to hang on the tree in the queen's garden.

In that same garden, the royal couple sipped wine from glass bowls that could have been brought as booty from the eastern Mediterranean region of Levant. One of these bowls, whose translucent yellowish-green color may have contrasted sensuously with the rich, red grape wine, can be viewed at the Suzhou Museum exhibition.

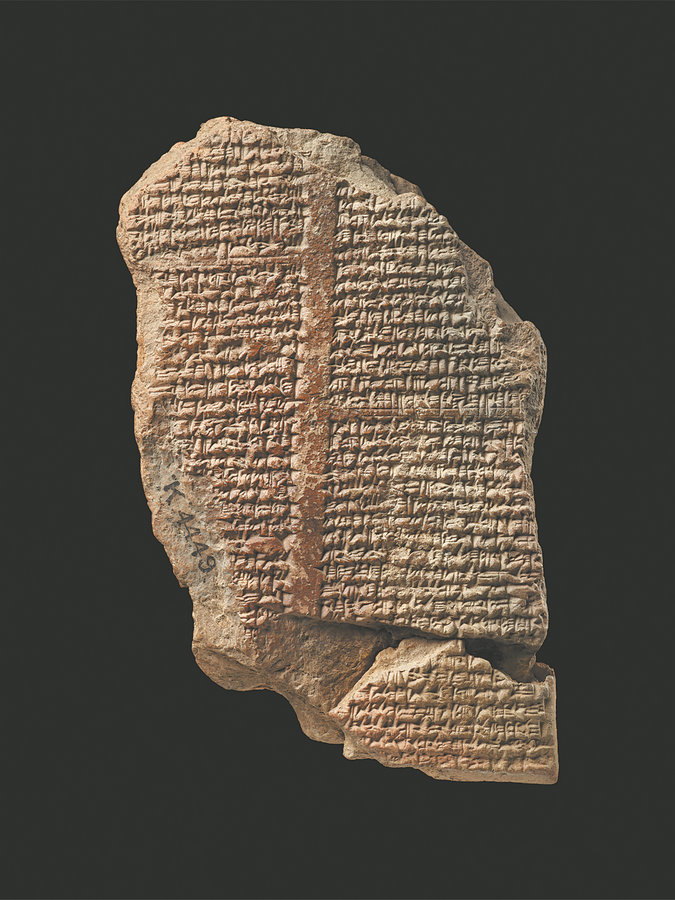

A particularly poignant object from the show is a cuneiform tablet — cuneiform being the wedge-shaped characters used in ancient Mesopotamia — that contains a letter from Shamash-shumu-ukin to Ashurbanipal. "You might be confident of an easy win but I will triumph in the end with a single brilliant move," the writer told his estranged younger brother as if they were again playing a childhood chess game.

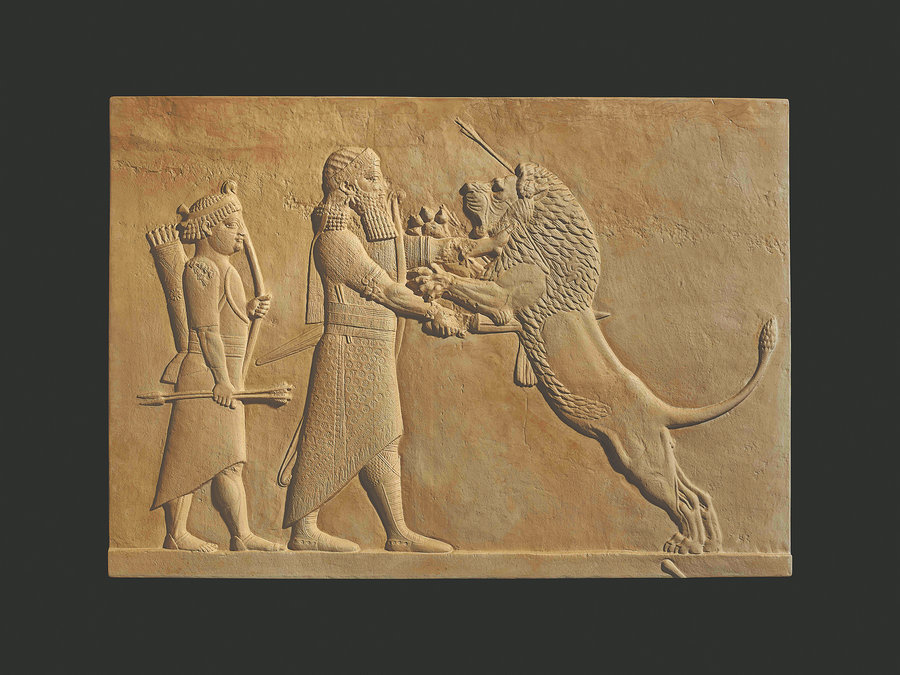

In 612 BC, less than two decades after the death of Ashurbanipal, a coalition of Babylonians and Medes sacked Nineveh, inflicting upon the city and its inhabitants a level of devastation not unfamiliar to Assyrian soldiers. The North Palace, whose exquisite reliefs showed the mighty king calmly stabbing a sword through the chest of a wounded lion, was set on fire.

Meeting the same fate was his royal library in Nineveh, which Ashurbanipal stuffed with tens of thousands of text-bearing clay tablets he had commissioned or amassed from all over his conquered lands in a dedicated effort to build what he considered to be the world's greatest temple of knowledge.

"The fire baked the clay, preserving for millennia Ashurbanipal's knowledge and legend," says Zhang.

Some tablets are labeled: Palace of Ashurbanipal, King of the world and King of Assyria.