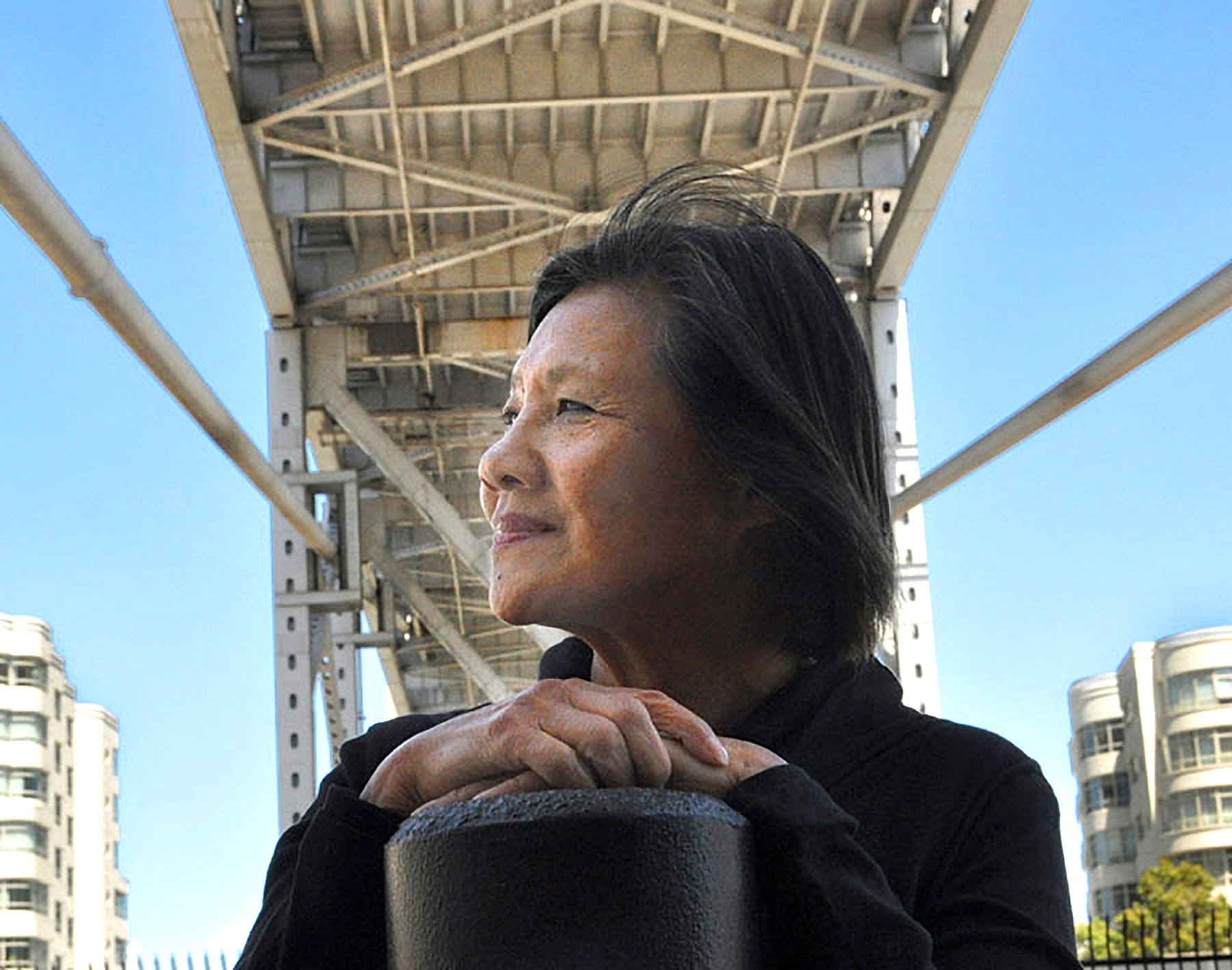

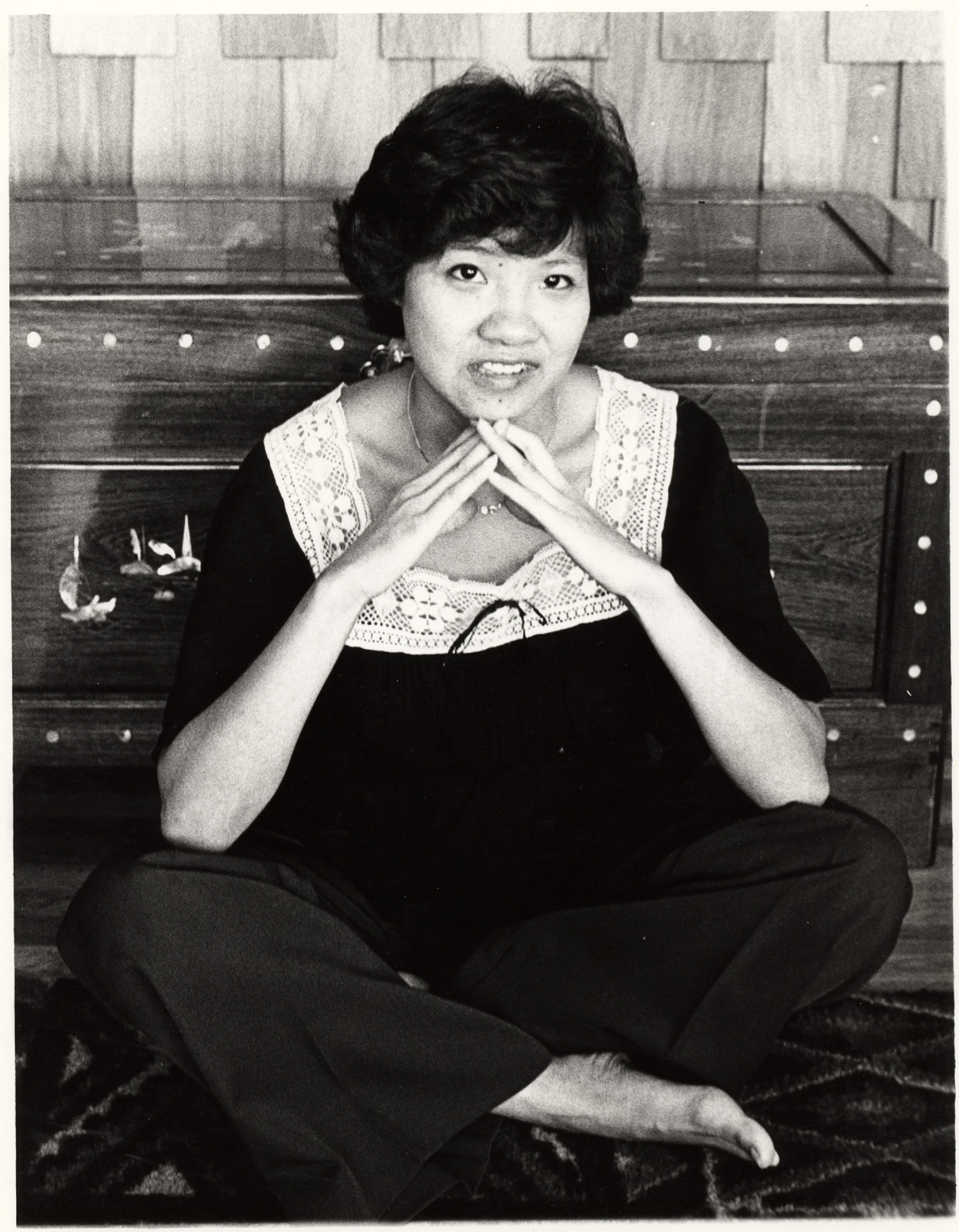

Genny Lim, who was recently named San Francisco’s first Chinese American poet laureate, tells Mariella Radaelli that she will continue to uphold the legacy of her Guangdong-born parents and champion the cause of fellow Chinese American artists.

In September, Genevieve Lim, who writes under her pen name Genny, became San Francisco’s ninth poet laureate. Lim is the first Chinese American recipient of the honor. Her parents, originally from Taishan in China’s Guangdong province, were first-generation immigrants to the United States. Lim was born in San Francisco in 1946 and grew up in the city’s Chinatown.

The poet, playwright and performer sees her new honor as a “significant and profound” milestone for Chinese Americans, especially since “historically our community has been marginalized even though we are a large percentage of the population in the San Francisco Bay Area”. Her hope is that the current focus on her role as a literary figure will eventually be extended to recognize the cultural contributions made by some of her fellow artists from the Chinese American community, which remains “drastically underrepresented in the arts”.

READ MORE: An explosion of verse

“My community puts so much hope in me, and I want to do my best,” she says.

In the name of her mother

Though she has never lived in China, Lim says that her writing is informed by Taishan culture. For instance, one of her most representative poems, Mothertongue (2017), evokes the sounds of the Hoisanwa dialect spoken by her Chinese ancestors. It is dedicated to her mother, Lim Lin-sun, who never learned to speak English.

As a child, Lim would feel embarrassed when her mother opened her mouth in public — “speaking an extinct language with a lot of inflections, tones, and pitches”. Lim Lin-sun ignored repeated requests from her daughter to switch to English, carrying on speaking in her native dialect, which “was very noticeable and idiosyncratic” even from the perspective of the family’s Chinese neighbors, many of whom were from “the educated classes who looked down on us”.

In order to counter such prejudice, “I had to resurrect my culture and language in a dignified, celebratory way, and with pride,” Lim says. To that end, she started The Last Hoisan Poets, a small writers’ collective that meets from time to time to read their works, written in both English and Hoisanwa.

Lim mentions that the presence of Nellie Wong, 90, and Flo Oy Wong, 86 — both daughters of Chinese immigrants from Tai-shan like Lim herself — in the group has led to “a renewed appreciation of and interest in the fading language and culture of our Taishan ancestors”. Inspired by them, some of the younger Chinese American writers in San Francisco have started “researching their own genealogies and family histories”. Lim herself leads an online memoir writing workshop, with a special focus on mining family narratives for material, for Asian American writers.

Southern voices

“Lim’s poetry is an important part of the canon of Chinese American poetry, notable for how it vividly captures certain elements — sights, scents, sounds — of the everyday lives of Chinese Americans in Chinatown,” says Juliana Chang, a professor of Asian American Literature at the Santa Clara University in California. “She writes poems about the unsung heroes of the community, especially women.”

Chang also mentions that Lim’s poems were a vital part of the blossoming of Asian American literature in the ’70s and ’80s. She considers the musicality inherent in Lim’s poems — particularly those included in collections such as Winter Place (1989), Child of War (2003), Paper Gods and Rebels (2023) for example — as one of her hallmarks. “She is influenced by the rhythm and cadence of jazz and blues music, and has performed with various jazz musicians.”

Lim herself says that the sonic rhythms of the language of her Chinese ancestors intersect with the improvisational nature of jazz music in her poems. She often incorporates elements of wooden-fish songs — a folk art form that combines storytelling with singing and is performed in a Guangzhou dialect — in her poems. Traditionally, wooden-fish songs — named after the fish-shaped musical instrument that’s integral to the performances — are sorrowful ditties. The themes range from missing a relative who went abroad to desertion by a spouse.

Lim says that she finds a resonance between Afro-American blues and wooden-fish songs. “Both involve tonal scales played on a minor key and come from the South,” she says, underscoring the fact that the melancholy tone in both is meant to express the hopes, despair and longings of the poor, dispossessed and marginalized communities.

Survival stories

Lim’s most significant contribution to American literature has to be her sensitive depiction of the immigrant experience in America.

“Lim is very attuned to the sensibilities of Chinese immigrants,” Chang says. “She writes about her parents, grandparents, ancestors and other immigrants with compassion and empathy, imagining their experiences and how they survived.”

Her award-winning play, Paper Angels — staged by the Asian American Theater Company in San Francisco in 1980 and subsequently televised by the Public Broadcasting Service — explores the history and emotional complexities of Chinese immigrants detained on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay for trying to enter the United States illegally. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had drastically limited Chinese immigration. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese arrived on the American shores with fake papers as a result.

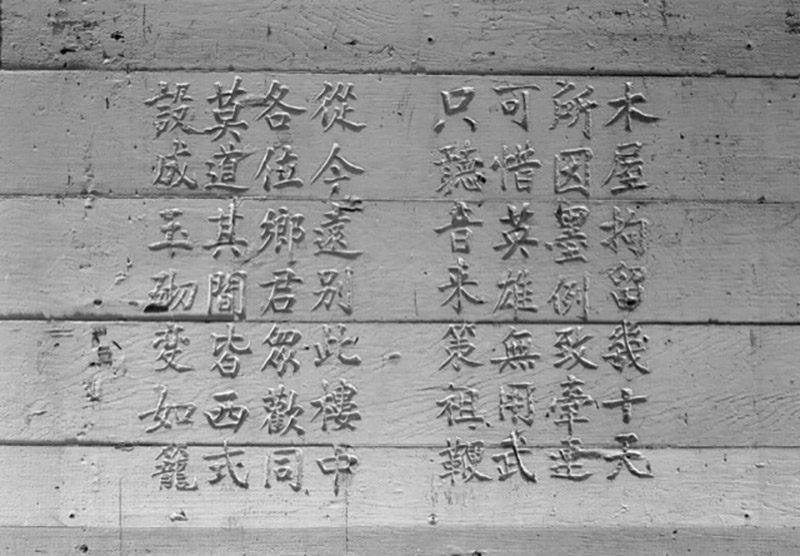

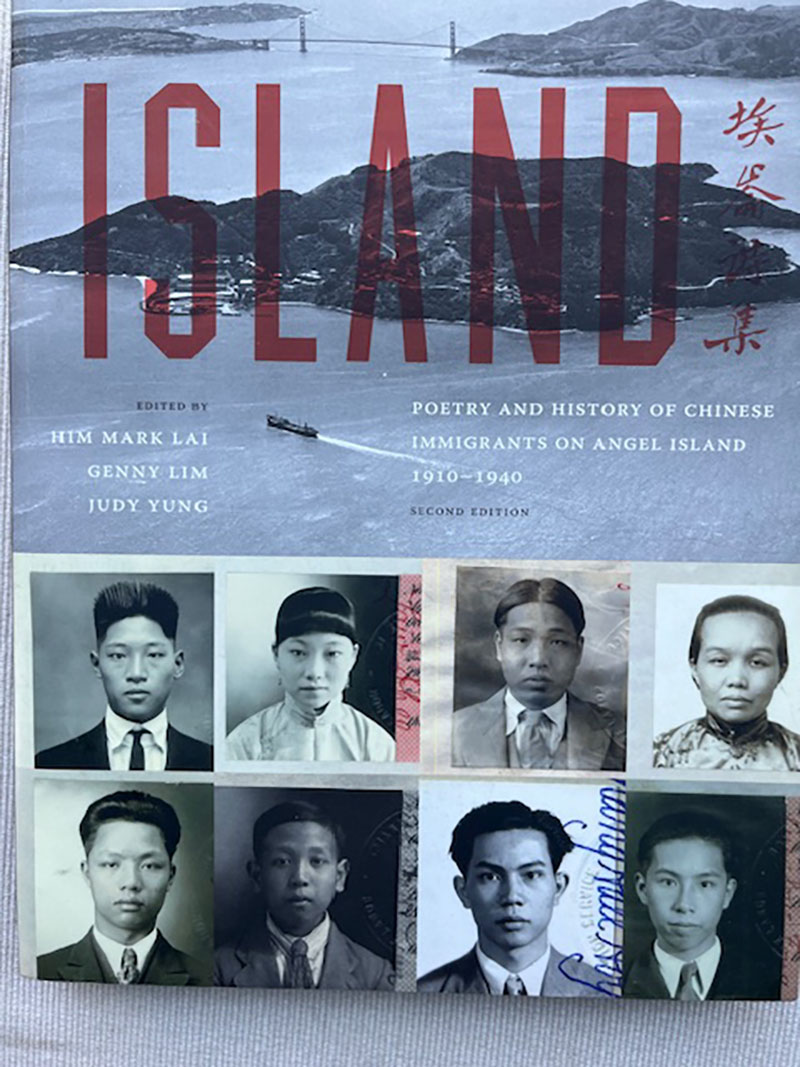

Some of the detainees who spent months waiting for clearance from the immigration department carved poems onto the barrack walls of the Angel Island Immigration Station. “They are all cries of complaint, sadness and loneliness,” says Lim, who started writing Paper Angels at the same time as she was putting together Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940. Co-edited with Mark Lai and Judy Yung, the book went on to win the 1982 American Book Award.

“Paper Angels is a composite of the different people we interviewed,” Lim says. One of its characters, Lum, is a romanticized depiction of the author’s father, who had been careful never to mention his detention to his children. “It was an episode in their lives that was so traumatic that they did not want it to be passed on to their children,” Lim says of a generation of Chinese for whom the American Dream was achieved at a high price. “They were treated as criminals, and the interrogations were arbitrary. Some of them were stuck in a dormitory for two years.”

Guiding light

As a child, Lim was more into singing and dancing rather than poetry. She remembers listening to her mother singing or chanting spells. For example, the mending of a hole in a dress was accompanied by Lim’s mother chanting a spell “to prevent negative spirits from entering the hole”. When Lim had nightmares, her mother would sing another spell in her ear. “I grew up with all these protective chants and beliefs in their potency. It was very powerful.”

ALSO READ: The world of Nancy Kwan

“It’s a celebration of our identity and a call to remember our roots as Lim’s words dive deep into our experiences, connecting generations through the Hoisanwa dialect and the immigrant journey,” says fellow poet Yang Jing Jing. “The Chinese American community looks to Genny Lim as a guiding light, knowing she will continue to amplify our voices and bring our shared histories to the forefront.”