What do new exhibitions in Hong Kong, Macao, Shenzhen and Guangzhou tell us about commercial and cultural exchanges between China and the rest of the world via the terrestrial and maritime Silk Road trade routes? Also what, if anything, do they reveal about our own times? In the first installment of an essay series, Chitralekha Basu dwells on the Silk Road’s role in bringing the world closer to China.

The Silk Road dominates the museum exhibitions scene in 2024. Inspired by this network of ancient terrestrial and maritime trade routes connecting the Eastern and Western hemispheres, this year, several museums in different parts of the world have put on Silk Road-themed shows or those embodying its spirit. From London (Silk Roads, British Museum) to Teheran (Endless Clouds of Silk Road, Malek National Library and Museum) to Tokyo (The Great Silk Road World Heritage Exhibition, Tokyo Fuji Art Museum), the Silk Road is the flavor of the season.

Among the plethora of such exhibitions held in China — which has the largest share in the area covered by the Silk Road trade routes by land and sea — a few among those located in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area come across as particularly noteworthy, and not the least because they display new information to creatively highlight how the three cities of Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Macao served as key ports, as well as manufacturing hubs, in the ancient Maritime Silk Route. More importantly perhaps, between them the 10 museum exhibitions in Hong Kong, Macao, Guangzhou and Shenzhen featured in this essay series demonstrate how the Silk Road continues into the present, and not just metaphorically.

READ MORE: The timeless allure of lavish clocks

Multiple, diverse and fluid

Contrary to popular misconception, the term “Silk Road” does not denote a single track running halfway across the world from Xi’an (ancient Chang’an) to Constantinople (Byzantium). Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen, a German geographer tasked with naming a proposed railway linking Beijing with Berlin in 1877, came up with the terms Seidenstrasse (Silk Road) and Seidenstrassen (Silk Roads), demonstrating an awareness of the fact that the concept was loaded with possibilities of multiplicity, flexibility and infinitude. Historian William Dalrymple writes in his new book The Golden Road that “it was not until 1938 that the term ‘Silk Road’ appeared in English, as the title of a popular book by a Swedish explorer, Sven Hedin”.

Over time the Silk Road has come to represent a map rather than a well-defined pathway. Today the term suggests an expansive and intricate web of land and sea routes that connected East Asia with Central, South, Southeast and West Asia as well as East and North Africa and Southern parts of Europe and one that was at its most active between second century BC and the 15th century.

Two of Hong Kong’s leading museum curators — Daisy Wang Yiyou, deputy director, curatorial, collection and programming at the Hong Kong Palace Museum (HKPM) and Libby Chan Lai-pik, director of the Indra and Harry Banga Gallery at the City University of Hong Kong — agree that the current surge of interest in Silk Road-themed exhibitions is at least partially owed to the Belt and Road Initiative, launched by President Xi Jinping. “It’s a theme people are asking about,” says Chan, who has co-curated the ongoing Might and Magnificence: Ceremonial Arms and Armor across Cultures exhibition. She describes the show as offering “cross-cultural perspectives on Asian ceremonial arms and armor as well as the exchanges between the East and West that took place as a result of the great voyages leading to encounters between different cultures”.

Rows and rows of slick and sparkling unsheathed blades and gem-encrusted scabbards meet the eye from all directions at the exhibition. It’s an awe-inspiring display, not just in terms of the volume of precious metal, gemstones and prodigiously talented craftsmanship assembled under one roof, but also because of the centuries of cross-cultural encounters that the exhibits have been witness to. For instance, the bejeweled gold hilt of an 18th-century Sri Lankan piha kaetta — hunting knife or dagger — was crafted and added in 19th-century France.

Though it is from a period when the Silk Road was past its heyday, the curatorial note on the object suggests that such products of cultural exchange materialized because the channels of communication were opened up “by the Silk Road and maritime networks”, leading “to a blending of traditional Eastern designs with European tastes”.

Ideas, people and objects

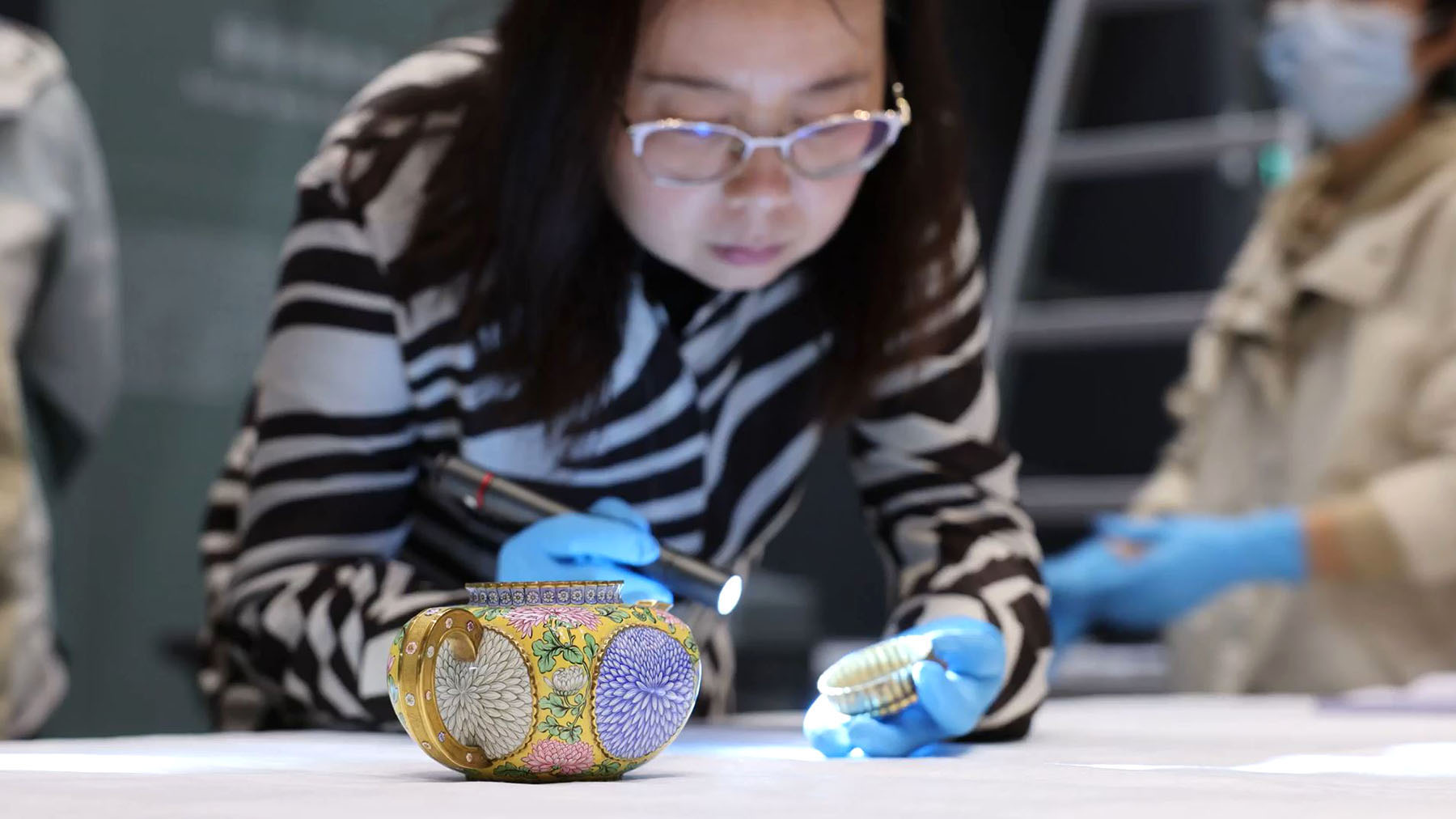

HKPM’s Wang played a key role in putting together The Forbidden City and the Palace of Versailles: China-France Cultural Encounters in the 17th and 18th Centuries exhibition, which opened at the museum on Wednesday. She says that “it looks at the concept of the Silk Road in the broader context”. The Silk Road, Wang emphasizes, is “not just about a particular period of time in history. … We look at it as a cultural phenomenon, and I would say this exhibition illustrates the spirit of the Silk Road, represented in the flow of ideas, people and objects.”

Specifically, the exhibition charts the relationship between China and France through the lens of the reigns of three French kings — Louis XIV (1643-1715), Louis XV (1715-74), Louis XVI (1774-92) and three Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) Chinese emperors — Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-35) and Qianlong (1736-95).

Wang’s three key markers of the Silk-Road spirit are in ample evidence at the exhibition. One of her personal highlights is the Qianlong Emperor’s image on a porcelain plaque from the Palace of Versailles collection. The piece is based on a sketch by an Italian missionary, Giuseppe Panzi, and realized on a porcelain plaque in 1776 by a French artisan, Charles-Eloi Asselin, at the Sevres Royal Porcelain Manufactory. In it the Chinese emperor is depicted as a robust authoritarian ruler with distinctly Caucasian features.

At the HKPM exhibition the French portrait is presented alongside an ink-on-silk scroll image of the Qianlong Emperor by a Chinese court painter. “I think together they make a fascinating example of how in the time of cross-cultural meetings one thing can be interpreted and presented in many different ways,” Wang says. She points out that a Chinese emperor’s portrait made by European artists on French soil, using a material that is generic to Chinese culture signifies a coming full circle of sorts. “The porcelain plaque painting of the Chinese emperor was probably made for sending over to China as a gift. The piece exemplifies a complex tapestry of cultural interactions.”

Science and mathematics

The presence of European Jesuit missionaries in the Qing court left an indelible and lasting imprint on Chinese culture, including the cultivation of science. Both the HKPM exhibition and the inaugural show of the new Poly MGM Museum in Macao, which opened its doors in November, display a few priceless scientific instruments brought over to the Qing court by Jesuit missionaries from the West. The HKPM show, for instance, includes a gilt silver armillary sphere inscribed by a French artisan, Ferdinand Verbiest, dated 1669, and a wood and gilded copper Pascaline calculator with French engraving. Both objects are from the Kangxi Period and on loan from Beijing’s Palace Museum.

Wang reminds us that Louis XIV had sent a mission of five Jesuit mathematicians to China during the Kangxi emperor’s reign. “The French Jesuits brought a lot of scientific knowledge to the Qing court, especially the technology of making clocks and timepieces. They also brought a lot of instruments of astronomy. So in this exhibition we feature timepieces, measuring devices and calculators. With the introduction of such instruments to the Qing court, some of the most advanced technology had entered China.”

She hastens to add that China had its share of mathematicians, mathematical devices and time-keeping systems at the time, “but embraced other ways of doing it”. “For thousands of years China was one of the most cosmopolitan states in the world. If you think of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) or the Han dynasties (206 BC-AD 24, 25-220), China has always welcomed people from the rest of the world and they in turn have contributed to the Chinese civilization.”

The same idea is beautifully manifest in some of the scientific instruments on display at the Poly MGM Museum show: The Maritime Silk Road: Discover the Mystical Seas and Encounter the Treasures of the Ancient Trade Route. These include a copper sundial compass with enamel work and a wooden cylindrical marine compass, both on loan from the collection of the China Maritime Museum and both Qing Dynasty exemplars of exquisite unions of form and function. Interestingly, the design of a Tang Dynasty gilt silver incense box owned by the Hong Kong Poly Art Centre seems to anticipate that of the 19th-century sundial in which the directions are marked in Chinese characters while the numerals appear in Arabic. Inside its trellised orb, the incense box hides a mechanism that can spin it like a gyroscope — applying a scientific know-how still in use in navigation and aviation.

Art finds a way

Some of the recent and ongoing exhibitions on the Chinese mainland have showcased fine specimens of the fruits of such cross-cultural exchanges that go back a millennium or more, and their existence is owed directly to that of the Silk Road trade routes. For instance, a band of painted ceramic figurines of musicians unearthed from a 728 AD tomb in Gongyi, Henan province includes a non-Chinese drummer. The models are on show at the From Central China to the Sea: Gongyi Kiln and the Maritime Silk Road exhibition at the Museum of Two Mausoleums of Southern Han State in Guangzhou.

Several exhibits at the Gandhara Heritage along the Silk Road exhibition hosted by the Shenzhen Museum of History and Folk Culture earlier this year also demonstrate how art and artists from the distant lands have been finding their way to ancient China. A copper alloy idol of the pensive, lotus-palmed Buddha Avalokitesvara that was crafted in India and traveled to China in the 18th century bears the generic features of Gandhara art: symmetrical and perfectly proportioned body parts, drooping eyelids and intricately arranged drapery. A historic document attached to the statuette written in Chinese and Manchu carries the precise date when it was received in China, corresponding to Feb 3, 1796, in the Gregorian calendar. That’s a date long after the eponymous art tradition that emerged during the ancient Indo-Aryan civilization of the Gandhara and thrived between the first century BC and the seventh century, and was no longer practiced.

Zhou Tingxi, the show’s curator, points out that while Gandhara art might have lost its home, the tradition had traveled to other climes. It was adapted by the artisans of “Swat, Kashmir, and Gilgit under the rule of the Turkic dynasties”, where newer hybrid artistic styles were being created. “These styles crossed the western part of Tibet and entered the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China, which provided sustenance for the development of Tibetan Buddhist art after the 10th century.”

ALSO READ: Cultural ties

High-quality art has a way of surviving the odds and reaching where it is appreciated. And their delicious and complicated survival stories are owed to the existence of the Silk Road.