Creating a comprehensive cultural database is long overdue in Hong Kong. Experts are banking on artificial intelligence to help preserve the city’s cultural heritage and boost the cultural industry. Oasis Hu reports in Hong Kong.

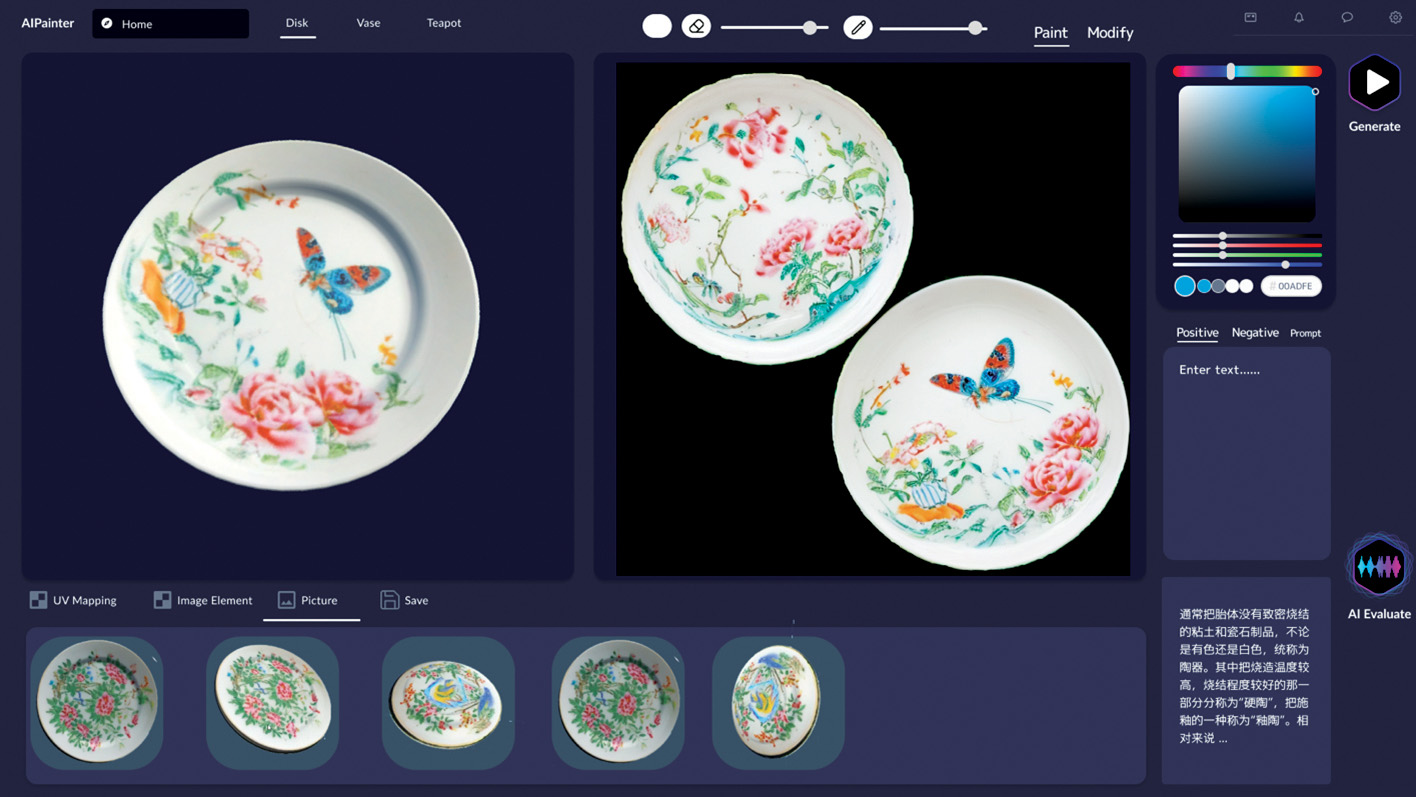

With the artificial intelligence software, Beauty of Cantonese Porcelain, even those new to painting can create their own Cantonese porcelain-style artwork in a matter of seconds.

Cantonese porcelain, also known as Kwon-glazed porcelain, is a kind of Chinese traditional ceramic art characterized by elaborate designs adorning white porcelain objects. These creations often depict flowers, birds, fish, mountains and seas, utilizing vibrant hues like red, green, and yellow. Due to its historical export channels through Guangzhou — previously known as Canton — and Hong Kong, this style of porcelain is called “Cantonese porcelain”.

Traditionally, crafting Cantonese porcelain design would take days or even weeks, but Beauty of Cantonese Porcelain can trim this down to just a few seconds.

Upon opening the software, a white disk is presented on the interface. Users input text such as “flowers” and click on the “generate” button. Then, a Kwon-glazed porcelain-style painting featuring flowers is soon crafted on the disk.

READ MORE: A fortress in the metaverse

This software is the first artificial intelligence (AI) generative tool dedicated to producing Kwon-glazed porcelain pictures. In other words, all pictures produced by the software are in the style of Cantonese porcelain.

Henry Duh, associate dean and professor in the School of Design at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and his team, have spent five years developing the AI tool.

He recalls that his initial motivation to develop the software stemmed from the cultural significance of the porcelain. With a legacy extending over three centuries, Kwon-glazed porcelain has earned a place on the national intangible cultural heritage list. Earlier this month, it was included in the representative list of the ICH inventory in Hong Kong. “AI is a good tool to preserve cultural heritage,” says Duh.

More importantly, he has developed this software to address a practical need.

About five years ago, Duh met some Cantonese porcelain masters in Guangzhou and found they frequently had to customize porcelain pieces for high-end clients. However, with the first batch of drafts and firing porcelain prototypes, customers often needed further adjustments, leading to a time-consuming cycle of redesigning, repainting and refiring demos before the final product.

Facing this challenge, Duh envisioned using AI to help designers create initial drafts. If clients approve these drafts, the process can move seamlessly to detailed designs and subsequent porcelain production; if clients request changes, AI tools can efficiently generate revisions, saving time and energy.

To fulfill this need, Duh had to develop an AI model specifically for Cantonese porcelain.

Given the extensive research on Cantonese porcelain and the presence of clear industry guidelines, designing the language model was not complex. According to Duh, the biggest challenge was data collection. Creating a specialized language model necessitates gathering a substantial volume of high-quality, high-definition images that prominently feature Cantonese porcelain.

However, Duh encountered difficulties in collecting data online as many images were of low quality and subject to copyright restrictions, rendering them unsuitable for training purposes.

He explored Hong Kong’s data websites for alternative sources, but was surprised that the city lacked a specialized cultural data repository. Moreover, many local museums did not disclose their collections online.

Shifting his focus to offline, Duh reached out to private collectors, but most were unwilling to allow their collections to be photographed.

Consequently, Duh and his team visited many museums, seeking permission to photograph Cantonese porcelain pieces in their collections. They also scoured numerous books on Cantonese porcelain, painstakingly entering a large volume of images from these texts into their dataset.

After years of effort, Duh and his team collected thousands of high-resolution photographs of Cantonese porcelain. The software was completed in October.

Through the AI tool, users can convert text into Cantonese porcelain-style paintings showcased on three-dimensional white porcelain. Users also have the option to paint directly on the white porcelain surface, with AI processing these images into Cantonese porcelain-style art.

Although the software is now just a research tool, it offers great potential for commercial use, says Duh. What is more, it shows the potential to use AI to generate a broader spectrum of traditional content if the dataset can be expanded.

For instance, by replacing all database content with neon sign images, users would be able to use the tool to customize neon signs. Similarly, a database filled with Hong Kong-style cheongsam designs could help generate cheongsam pictures effortlessly. “Of course, the key prerequisite for this expansion is the availability of data related to these cultural elements online,” Duh says.

Data pool required

Josselyn Chau, assistant researcher at Our Hong Kong Foundation, notes that Hong Kong has long grappled with the problem of inadequate online cultural data. In the digital age, cultural infrastructure extends beyond physical establishments like the West Kowloon Cultural District to encompass online resources, with cultural data serving as a cornerstone, she says.

Cultural data can be categorized into different types, including cultural assets, such as online museum collections; data on cultural participation, such as attendance metrics at cultural venues; and data on the cultural industry, such as revenue statistics from sectors like the media, film, tourism, music and theater.

Each type of cultural data has its benefits. For instance, data on cultural assets can aid in managing, preserving, and disseminating cultural content and nurturing cultural education and innovation. Data related to cultural consumption empowers organizations to adapt policies, products, and services in alignment with market dynamics. The greater the amount of data available, the more effectively the government can comprehend the cultural ecosystem of a region, leading to improved policymaking.

A greater volume of data also enables the public to engage in a wider array of cultural initiatives, fostering a more dynamic cultural landscape. As a result, many regions worldwide are actively digitizing their culture, Chau says.

As of 2017, the Chinese mainland has been issuing multiple documents to foster the growth of digital culture and propel the establishment of cultural data infrastructure. A prime example is the Palace Museum in Beijing, which has digitized the cultural content and identity information of more than 100,000 relics and made them accessible to the public.

Following a similar trajectory, in 2021, Taiwan inaugurated a four-year program to amass cultural data for policymaking and public use.

In Hong Kong, the special administrative region government launched the Smart City Blueprint in 2017, followed by an updated version in 2020. These blueprints detailed hundreds of initiatives applying technology in various sectors like mobility, environment and the economy, but they did not mention cultural areas.

In 2020, the concept of “art tech” was introduced for the first time in the Policy Address, allocating HK$100 million ($12.82 million) to four arts funds to support the development of art technology. However, a cultural data infrastructure was yet to be mentioned.

Neglecting cultural digitization has led to challenges for the city in accessing cultural data online, says Chau. For example, Taiwan has a dedicated cultural statistics website that offers a centralized hub for a wide range of updated cultural data, including information on cultural budgets, cultural venues, film releases and cultural assets. Hong Kong lacks such an online hub.

Cultural data in Hong Kong is dispersed across various websites managed by different bureaus, such as data.gov.hk, the Leisure and Cultural Services Department’s Museums Collection Search Portal, the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, and the Cultural and Creative Industries Development Agency.

Each of these websites contains some cultural data, but none of them offers a comprehensive and holistic view of cultural data, resulting in a scattered and partial representation of the cultural landscape. Such an unregulated approach could confuse users and government departments in seeking specific cultural data.

Various government departments also use different standards in collecting cultural data, posing challenges for residents in consolidating and utilizing it.

Furthermore, the quality of cultural data on these websites is often poor. For instance, the Museums Collection Search Portal, maintained by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department, often lacks details and high-quality images of the collections, hampering its effectiveness, according to Chau.

Cultural bias

William Wong Kam-fai, a lawmaker and an expert in web databases, is worried that inadequate cultural data could not only hamper the city’s cultural industry, but also pose a risk of missed opportunities. One specific area where this deficiency is apparent, according to Wong, is the digital intellectual property industry.

For example, South Korea established the Digital Copyright Exchange (DCE) in 2007 under the Korea Copyright Commission. The DCE is a central platform that offers an array of copyrighted works and licensing options. With an extensive database comprising over 30 million entries, covering literary, musical, visual, and audiovisual works, the DCE facilitates online transactions for cultural intellectual property (IP). Users are able to purchase licenses directly from copyright owners through the website.

In contrast, Hong Kong lacks a digital IP center or trading platform for cultural assets.

AI art is another example. Last year, the global AI art market reached $3.2 billion. Projections suggest that by 2033, the market could catapult to about $40.4 billion, reflecting an annual growth rate of 28.9 percent.

However, in Hong Kong there are challenges in creating local AI art due to insufficient data, says Bianca Tse Wai-shan, a local AI artist. She has a profound appreciation for local culture, with most of her artwork rooted in the city’s distinct cultural icons.

Captivated by the Kowloon Walled City, a once lawless enclave nestled in the heart of Kowloon that met its demise in 1994, Tse chose this historic locale as the focal point of her artistic exploration. However, as she delved into her work, she encountered a dearth of available information about this site.

“I can only find information from some photographs or illustrated books, but all of them were authored by foreigners,” says Tse. “Hong Kong itself didn’t seem to place much emphasis on preserving its own cultural heritage.”

A lack of cultural data can also lead to cultural misunderstandings and prejudices, she says.

When Tse attempted to use AI to create images of Hong Kong children holding windmills at Che Kung Temple in Sha Tin for the coming Lunar New Year, she encountered a surprising cultural disconnect.

At the heart of the temple stands a bronze statue of Che Kung, a Song Dynasty (960-1279) commander honored for leading residents to combat plagues. Legend has it that spinning the fan-shaped brass wheel beneath the statue brings good fortune, thus inspiring the tradition of bringing home windmill-shaped merchandise from the temple.

The AI software, when prompted with the “windmill” keyword, predominantly generated images of Dutch windmills — towering structures with large wind wings — rather than the small, red plastic paper windmills that are iconic to Hong Kong’s tradition.

This shows that pre-existing datasets and algorithms may not adequately represent the diverse and nuanced characteristics of localized cultural concepts, explains Tse.

To ensure the faithful representation of Hong Kong’s cultural heritage in digital areas, there is a critical need for curated datasets that encompass a wide range of culturally specific imagery, she says.

ALSO READ: Expo showcases AI revolution in education

Tobby Kan Shiu-tao, a senior lecturer with the Department of Digital Arts and Creative Industries at Lingnan University in Hong Kong, says the SAR government needs to establish a comprehensive cultural database as soon as possible.

“Cultures are susceptible to disappearing over time due to various factors, such as destruction or replacement with other influences. Without proper preservation, there is a risk that these cultural treasures may one day be lost forever,” says Kan.

In his view, the government’s first step should involve defining the scope of what should be recorded, and then prioritizing them based on scientific standards.

He would like the authorities to collaborate with museums, nonprofit organizations, universities and private companies in gathering data. Residents should also be encouraged to get involved through different incentives.

“It’s a long road, but it’s worth going,” says Kan.

Contact the writer at oasishu@chinadailyhk.com