For the West, democracy is a form of government in which supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodic free elections, which are contested by more than one party. This, the West believes, helps voters to fulfill their personal and national aspirations, and the political parties, which represent voters based on their ideological and political beliefs, to enact policies to suit their vote banks. In a democratic system, voters of all persuasions find a party that identifies with their core convictions and ideology on the most relevant issues.

But far from being an ideal scenario, in a majority of countries in the West as well as the Global South, the parties with a real chance of forming a government are limited to two or, at best, three in number. During political campaigns, each party uses propaganda to settle scores with the other contenders, and even after one of them wins the election, government policies on some of the most basic issues hardly change.

READ MORE: US Congress certifies Trump election victory with Harris presiding

The US is a good case in point. In the United States, only two political parties have the chance of forming a government or gaining majority in the House of Representatives and the Senate. To be sure, there have been instances in which the two parties have had meaningful differences on substantive issues but such instances have been few and far in between. One example is their approach to slavery: the Republican Party opposed it while the Democrats supported it. But in modern times, their stances on private property, the role of market forces, military expenditure and global policing, self-bestowed by the US, have been practically identical.

As is customary, the core strategy of the election campaigns of the two parties is to portray the other to be at the far end of the ideological spectrum. In fact, if the just-concluded campaign hyperbole were to be taken seriously, we would have to believe that president-elect Donald Trump's ideology is "totalitarianism" while incumbent Vice-President Kamala Harris' is "socialism". If that were the case, voters would really have different choices and the US would have a true bipartisan system.

But the fact is that regardless of who becomes the new lodger in the Oval Office, the US will continue to be a private sector, market-oriented economy; a defender and practitioner of press freedom and freedom of expression; the strongest military power on the planet; the staunchest ally of Israel; a trigger-happy marauder in world affairs; a leading member of NATO; a key player in world trade and foreign direct investment flows; and tough on migrants and nosy about human rights if violated in countries that it deems as rivals or enemies.

Even on the issue of trade, the protectionist approach of Trump was largely adopted by President Joe Biden. Something similar happened on migration, as even Harris supports the wall along the border with Mexico, a hallmark of Trump policy.

Of course, the policies that Trump and Harris, during their campaign, proposed on abortion, gun control, immigration, climate action and taxation were different. But at the end of the day, even on these issues, the difference in actual policy outcomes would be little.

Terrified by China's increasing industrial and technological competitiveness, Trump has vowed to impose up to 60 percent extra tariffs on Chinese products. He might even strengthen economic and military alliances against China in Asia and beyond. But to believe the actual policy under a Harris presidency would have been different would be wishful thinking.

Despite the room for ideological diversity granted by democracy, how could the actual outcomes be so homogenous? First, because regardless of press freedom, the US' media outlets, beyond their bombastic posturing, hold an identical position on core issues.

Second, the very visible failures of planned economy and the success of those economies that have created enough space for private initiatives and market forces to operate have been a strong stumping factor for the US' political system.

Third, and most important, money is a key factor in US politics, so much so that political analysts and pundits, when forecasting election results both for the White House and Capitol Hill, accord the greatest importance to corporations' contributions to the two parties' candidates as a deciding factor. The limit on donations was abolished by the US Supreme Court in 2010 through its decision in the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case.

ALSO READ: US’ double standards weaken its global credibility

Since then millionaires and billionaires have been filling up the two parties' coffers, with the parties splurging the donations on their political campaigns. In fact, it is estimated that in 2024 total spending to elect a US president and members of Congress hit at least $15.9 billion.

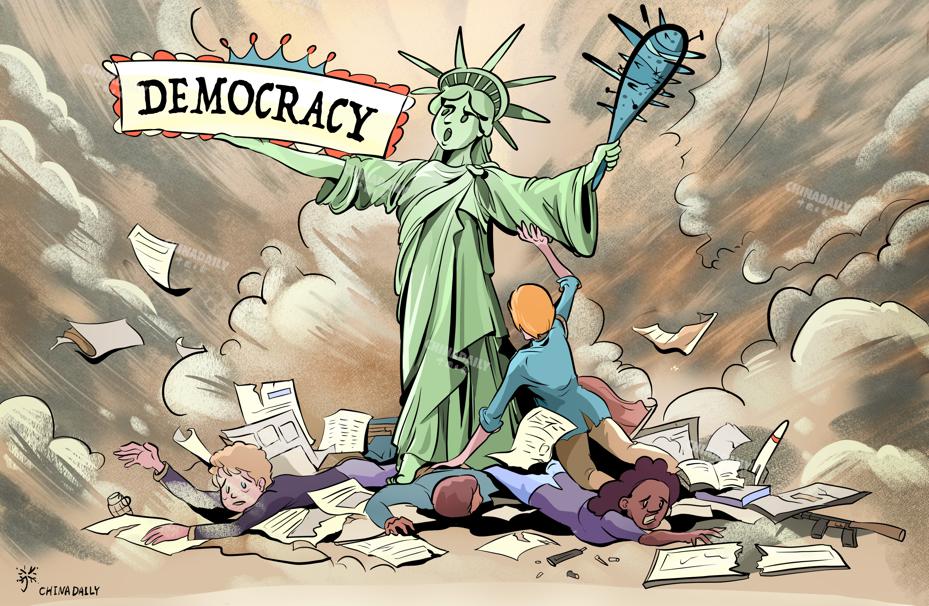

When money plays the key role in election success, the political discourse across parties and candidates becomes homogenized, and revolves around the ideology and the whims of the moneyed class. As such, the expected diversity of thought across the political spectrum has become just a theoretical component of most Western democracies, especially US democracy.

Perhaps it would be far-fetched to say that in the US, mindless of the fact that legally there can be many political parties competing for power, from the point of view of ideology and core policies, money has helped create a de facto one-party system. The path that will be followed by the US under Trump will therefore not be very different to what would have happened should the Democrats have won the presidential election.

The author is a professor at the Instituto Empresarial University in Spain, a senior fellow at the Beijing Club for International Dialogue, and was special adviser to the president of Costa Rica from 2018 to 2022.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.