Archaeologists uncover new facets of Beijing’s history with capital city, ancient city gate among the discoveries

Fresh stories of Beijing’s long history are gradually emerging, thanks to hard work by archaeologists. Details of new discoveries spanning 2,000 years from the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC) to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) have recently been released by the Beijing Municipal Cultural Heritage Bureau.

The city’s stint as the national capital began 871 years ago when the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) moved its capital to Beijing in 1153, calling it Zhongdu (“the central capital”). It was located mainly in what is today’s Xicheng and Fengtai districts.

The recent discovery of a gate from the Jin Zhongdu era is among the highlights revealed by archaeologists.

“This is our first discovery of a Jin Zhongdu gate, and also our first time excavating one of them,” said Ding Lina, a researcher at the Beijing Institute of Archaeology. “It’s a rare example of a large-scale building foundation on this site discovered with its structure intact.”

The gate is composed of two piers on the eastern and western sides of a 6-meter doorway, which reveals traces of wheels and possibly hoofs, suggesting the coming and going of carriages and people on horseback, Ding said.

Outside the gate is a horseshoe-shaped wengcheng, a type of defensive enclosure often built outside city gates in ancient China.

Inside the city, the remains of two streets have been discovered.

According to Guo Jingning, director of the Beijing Institute of Archaeology, although the rulers of the Jin Dynasty were the Jurchen people, nomads from what is now northeastern China, they made use of many Confucian ideas from the Central Plains in the building of Zhongdu.

“For example, they built gates for the city, whose names included the characters for ren (benevolence), yi (righteousness), li (propriety) and zhi (wisdom), some basic moral principles advocated by Confucianism. Among them was a southern gate called the Duanli Gate,” Guo said.

Ding said the location of the discovery aligns with historical records, and its shape and size all suggest that it was the Duanli Gate.

“In the past, our understanding of Jin Zhongdu was limited to literature and a few archaeological discoveries, but we had failed to find such a landmark structure. The study of an ancient city is not complete or satisfactory before finding its gates and streets, and efforts this time helped fill in the blanks,” Guo said.

Zhang Lixin, director of Beijing Municipal Cultural Heritage Bureau, said the discovery was testimony to Beijing’s history as a capital for more than 870 years.

Beijing boasts eight UNESCO World Heritage Sites, among them the Great Wall. Ongoing archaeological efforts on the Jiankou Great Wall in Huairou district, a section built during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and known for its steep ridges and rugged terrain, have revealed surprising details about its color.

According to Shang Heng, an associate researcher at the Beijing Institute of Archaeology, traces of red were found in June on the window of a lookout tower on the Jiankou Great Wall, which echoes details of a Ming Dynasty map in which the wall was painted red.

“This was the first time we found red pigment on the Ming Great Wall,” Shang said. “At first, we thought it was decoration, but later we realized the window was probably red during the Ming period.”

The traces are clearly visible and linear. Shang noted that as windows are exposed to the elements, their surface is often weathered, leading to bleaching, so it is rare for color to be identifiable after nearly 400 years.

Shang said the major requirement of the Great Wall during the Ming period was that it be solid and imposing, and painting it red was probably a way to add its grandeur.

“In the past, our understanding of the Great Wall was that it was gray, but this new discovery has shown us that its red color would have looked more beautiful in the wild,” Shang said.

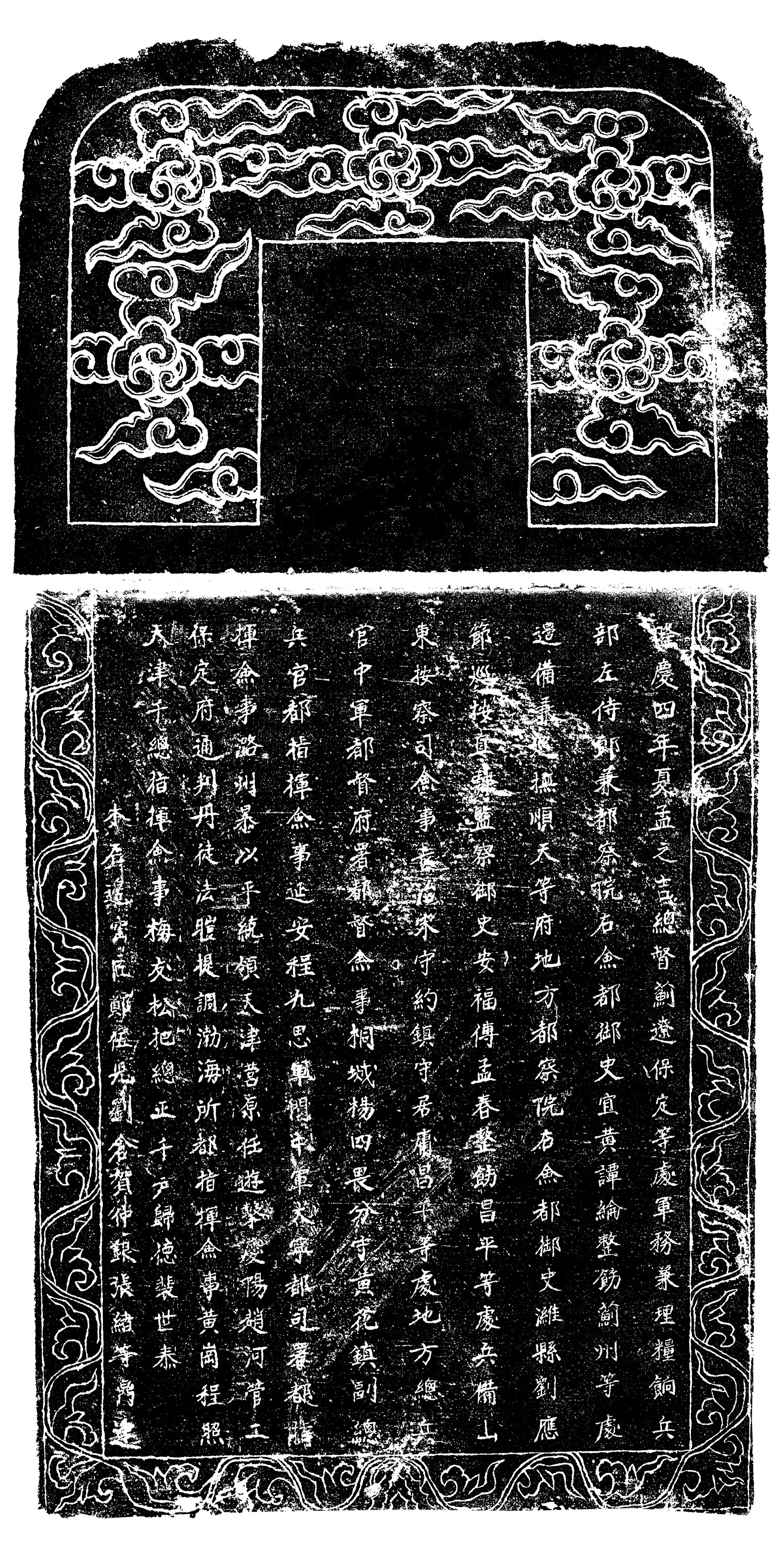

Archaeologists also discovered the earliest stone tablet found so far on the Jiankou Great Wall in another lookout tower, which records its date of construction and the names of its builders.

“We have pursued archaeological studies on the Great Wall for many years, achieving remarkable progress. This time we discovered the red pigment, which indicates that our excavation has become more precise,” Guo said.

The latest discoveries have also shed light on another World Heritage Site: the imperial tombs of the Ming and Qing dynasties. Beijing has long been known for the tombs of 13 Ming emperors and their families in Changping district, but in 2022, archaeologists discovered a new imperial graveyard at the foot of Xiangshan Mountain, and began excavating.

Zhang Lifang, an associate researcher at the Beijing Institute of Archaeology, said the graveyard is ringed on three sides by mountains, and has three south-facing cemetery complexes ranged from east to west.

“The three complexes have clear layouts and intact structures of tombs and memorial halls,” Zhang Lifang said.

Based on epitaphs found on the site, and the layout of the tombs, archaeologists believe the eastern complex was for imperial children who died young, among them, Princess Yunmeng, one of Emperor Wanli’s daughters.

Lying beside her is a tomb inferred to belong to her sibling Zhu Changxu, who died soon after birth and whose mother was Emperor Wanli’s beloved concubine.

Zhang Lifang said the layout of this complex is very similar to the tomb of Emperor Wanli, which has been excavated and is open to the public.

The middle complex belonged to Emperor Jiajing’s concubine, surnamed Wang, and the western complex possibly contained the tombs of several concubines buried together.

Archaeologists also found sacrificial vessels, stone tables, thrones, bottles and wooden figurines in the tombs.

“This is the largest imperial tomb group we have excavated since the Ming tombs in Changping. Although some have been destroyed or looted, their remaining layout, size and artifacts demonstrate their scale and strict building methods,” Guo said.

“This provides a direct reference for understanding imperial burial customs, rites and the engineering of the dynasty.”

Other discoveries released include the analysis of female bones found in a well at the Luxian Gucheng Site in Tongzhou district, identified as the location of Luxian county during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24), which revealed how they died, and the possible reasons for their deaths, as well as an imperial stone road dating back to the Qing Dynasty in Fengtai district.

“We have uncovered many of the human stories behind the heritage,” Guo said. “Through archaeological discoveries we can make guesses about life and death in ancient times, as well as the experience of those who lived then to develop a better picture of society at the time.”