Exhibition showcases cultural heritage drawn on early cross-border Buddhism exchanges

Curator Luo Wenhua (first from left) introduces a stone carving to visitors at the exhibition, Gandhara Heritage Along the Silk Road, in the Palace Museum in Beijing on March 15. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

Curator Luo Wenhua (first from left) introduces a stone carving to visitors at the exhibition, Gandhara Heritage Along the Silk Road, in the Palace Museum in Beijing on March 15. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

In the year 399, not long after the Roman Empire split into its western and eastern halves, Chinese Buddhist monk Faxian embarked on an arduous journey from China to India by foot to acquire Buddhist sutras. He traversed the deserts of Central Asia and trekked through the mountain passes, in what is today northern Pakistan, to visit major centers of Buddhist learning, before returning home via sea with a priceless trove of Buddhist classics.

His footsteps were later followed by pilgrims like Song Yun, Huisheng and Xuanzang, who built on Faxian’s work, translating Sanskrit texts and popularizing Buddhism, which spread across East Asia. Their arduous journeys in search of mysterious learning, often memorialized in their writings, constitute an important chapter of early communication between Chinese and other civilizations.

The historical roots of these tales can be traced in an ongoing exhibition, Gandhara Heritage Along the Silk Road, at the Palace Museum in Beijing, also known as the Forbidden City.

Organized by the Palace Museum and the Department of Archaeology and Museums of the National Heritage and Culture Division of Pakistan, the Pakistan-China joint exhibition kicked off in Beijing on March 15, and will run until June 15.

A gold earring on display at the ongoing exhibition. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A gold earring on display at the ongoing exhibition. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Gandhara, an ancient region spanning what is now northwest Pakistan and parts of east Afghanistan, was historically a crossroads linking India, Persia and other cultural centers as far away as ancient Greece.

Pakistan is home to many archaeological sites left behind by the inhabitants of this ancient melting pot, and a variety of the relics excavated there have been transported to Beijing to be displayed at the exhibition.

The exhibition features a total of 203 artifacts from Gandhara, including stone carvings of the Buddha and various Bodhisattvas, remnants of Buddhist pagodas, gold and silver items and jewelry. The finds represent a large chunk of the region’s history, from the 2nd century BC to the 10th century AD.

On loan from seven museums in Pakistan are 173 of the artifacts. The rest are from the Palace Museum, the imperial palace of the Ming and Qing (1368-1911) dynasties, and first traveled to Tibet, from which they were presented as gifts.

A gold stupa-shaped Buddha reliquary on display at the exhibition. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A gold stupa-shaped Buddha reliquary on display at the exhibition. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Gandhara Buddhist art — which originated in the Kushan Empire, a Central Asian state founded by Indo-European nomads originally from China’s Gansu province and Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region — is a unique art style that blends Greco-Persian and Buddhist influences. “And that is where its charm lies,” said Luo Wenhua, the exhibition’s curator.

“Gandhara art brings two major changes. On one hand, the art form exerted an influence on the neighboring regions where people followed Buddhism, including China. On the other hand, it created the first images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.”

Before the birth of this art, there were no images of the Buddha. Rather, people worshipped things related to him, like his footprints and turban. The exhibition shows Buddha footprint carvings and stonework depicting deities worshipping his turban.

“We cannot see Buddha in the carvings, but we can feel his presence,” said Luo.

A visitor examines one of the exhibits said to be Buddha’s footprint in stone.

(JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

A visitor examines one of the exhibits said to be Buddha’s footprint in stone.

(JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

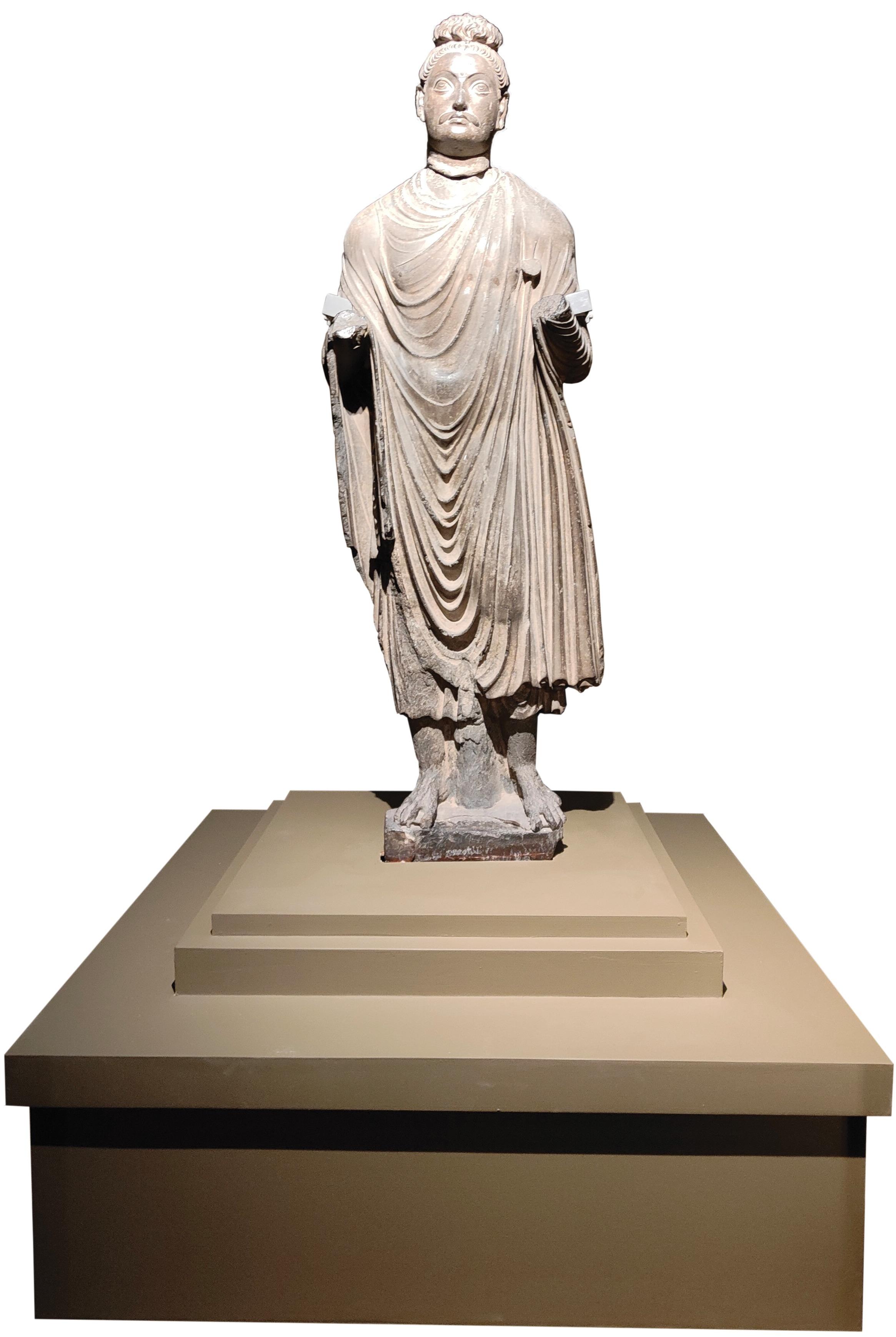

A highlight of the statues on display is a standing Buddha nearly 1.8 meters high. He is barefoot, wearing a robe. He lifts his left foot slightly, revealing a little of his left knee.

“This shows that he is ready to leave,” said Luo. “The Buddha’s curly hair, his face and clothes are all in typical Greek style, but he has an urna (a spiral or circular dot on the forehead), a symbol of Buddhism, which means the statue is carved in accordance with Indian Buddhist classics. Therefore, it is a combination of Greek and Indian culture. This Buddha figure style later profoundly influenced similar figures in the Yungang Grottoes and Mogao Caves, ancient Buddhist sculptural sites in China.”

Besides Buddhist artifacts, the exhibition also shows some everyday objects related to people’s ordinary lives. For example, there is a gold earring in the shape of a leech. The bent leech forms a moon-like ring. Linking the ring is a smaller moving ring which connects to a flower bud-shaped pendicle on the other side.

“From this earring we are amazed at how sophisticated and developed their handicrafts were,” Luo said.

Photographs are taken of the stone artifact.

(JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

Photographs are taken of the stone artifact.

(JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

Gandhara artifacts traveled to China in two ways. One route, passing through what is today’s Xinjiang and Gansu, is well-known, but the other, ascending the Indus Valley into the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, is less known, Luo noted.

A copper statue of the Guanyin Bodhisattva on display at the Palace Museum has Tibetan inscriptions on its lotus-shaped pedestal. It was produced in Swat in the 7th to 8th century. “It shows that Tibetans got Buddhist statues from Gandhara, and put them in their temples to worship,” Luo said.

Another Tibet-made copper statue dating from the 11th century of Manjusri, the bodhisattva personifying supreme wisdom, shows stylistic borrowing from images made in Swat, Gilgit and other places in the region.

“Through this exhibition, I want to highlight the fact that the Silk Road was not just a single route, but was a network which could reach the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau,” Luo said.

A standing Buddha statue on show is a combination of Greek and Indian culture.

(WANG RU / CHINA DAILY)

A standing Buddha statue on show is a combination of Greek and Indian culture.

(WANG RU / CHINA DAILY)

“Cultural communication between our two countries has a long history,” said Mahmood-ul-Hasan, deputy director of the Department of Archaeology and Museums of the National Heritage and Culture Division of Pakistan. “Archaeological studies prove that as early as the late Bronze Age, people who lived in Sichuan province had established close cultural contact with people of the Indus Valley civilization, and such links were strengthened during the Iron Age.

“In the first century, Buddhism spread from Gandhara to China through the Silk Road. We have found a large number of Buddhist figures influenced by Gandhara culture at sites on the Road in China, and also many stone carvings and Buddhist pagodas with Chinese characteristics in Pakistan. They bear witness to the thousands of years of cultural communication between us.”

According to Wang Yuegong, deputy director of the Palace Museum, the Gandhara art exhibition is the biggest of its kind ever held in China. It was first conceived of in 2019 to celebrate the 70th anniversary of China-Pakistan diplomatic relations in 2021, but was postponed due to COVID-19.

“People can get a glimpse of the charm of the art and culture of the Gandhara area through these relics, and feel the sparks coming from the collision of different civilizations and religions,” said Hasan. “I hope these artifacts, with their rich connotations, will offer inspiration to visitors.”