This undated photo shows Napoli's Stadio San Paolo in Napoli, Italy. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

This undated photo shows Napoli's Stadio San Paolo in Napoli, Italy. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Italian soccer has fallen a long way from its heyday. Now, the chance to refurbish one of Europe’s top leagues to its former glory has attracted interest from a clutch of private equity firms who are betting on getting a bargain.

Private equity firms including Advent International and Bain Capital are considering bids for a stake in a league division that manages TV rights, Bloomberg News has reported. The Serie A league has hired Lazard as an adviser and bids are expected by July 25, people familiar with the talks said, asking not to be identified because the deliberations are private. No final decisions have been made and a deal may not go ahead, they said.

Private equity firms including Advent International and Bain Capital are considering bids for a stake in a league division that manages TV rights, Bloomberg News has reported

Representatives for Serie A and Lazard declined to comment.

The winner has its work cut out. When Diego Maradona played for Napoli more than 30 years ago, the inspiration for Asif Kapadia’s 2019 film on the Argentinian player, San Paolo’s stadium was a centerpiece of Italian soccer. It was one of the venues for the FIFA World Cup in 1990. But in a 2018 radio interview, the president of Napoli called the team’s colossal stadium “a toilet.” It’s been partially refurbished since, but illustrates the league’s need for investment.

Shutdowns from the COVID-19 pandemic have strained the league further, potentially making it a bargain for a bidder. After a three-month lockdown and with the threat of stadiums sitting empty for the rest of this season and the start of next - depriving the sport of ticket sales, TV revenue and hospitality - some teams are financially stretched. And accumulated debt is rising. The figure for the league is about 1.3 billion euros (US$1.5 billion) for the 2018-2019 season, according to analysis of 18 out of 20 clubs by KPMG.

ALSO READ: Italy soccer chief hopes for fans in stadiums before season end

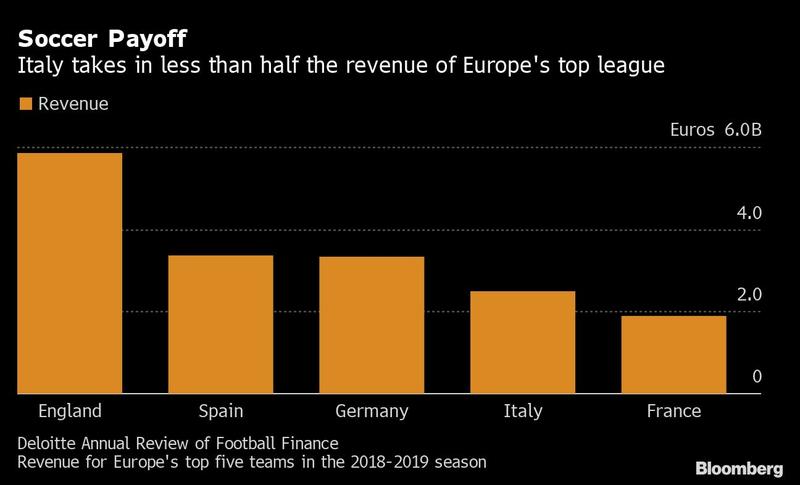

Serie A ranked fourth out of the five biggest European leagues by revenue in Deloitte’s annual review of soccer finance. Its revenues for the 2018-2019 season were less than half of the wealthier English Premier League at just under 2.5 billion euros.

The key to turning the league around may be television rights, the fuel behind the Premier League’s financial performance. Payouts from the rights to broadcast matches remain relatively low and suffer from a lack of competition in Italy. Sky and streaming service DAZN carve out domestic rights to the live matches between themselves. England’s league made about 3.5 billion euros from broadcasting rights in the 2018-2019 season compared to 1.46 billion euros in Italy, according to Deloitte.

The key to turning the league around may be television rights. Payouts from the rights to broadcast matches remain relatively low and suffer from a lack of competition in Italy

READ MORE: Serie A asks broadcasters to make payment for this season

The chairman of AC Milan, Paolo Scaroni, said on Bloomberg TV that there were lots of markets where Italian soccer could do better, naming India and China as examples.

“Serie A is not receiving the amount of money we should be,” Scaroni said, and added that the offers from three private equity firms value the rights higher than what they’ve been getting for the last couple of years. “We are reviewing as a league all of our strategy because we need to improve the revenues coming from the Italian TV rights and international TV rights.”

Utilization of stadiums - which, with the exception of a few modernized ones such as Juventus and Udinese, remain unappealing to many fans - was also the lowest of the top five European teams, with just 61 percent of seats filled, according to the Deloitte report.

The stadiums, mostly owned by local councils, have had trouble finding funds and overcoming bureaucracy to modernize.

Genoa Cricket and Football Club, known as Genoa, is Serie A’s oldest soccer team, founded in 1893. After Italy’s lockdown, Genoa applied for a 7 million euro state-backed credit facility, according to people familiar with the matter. Like Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV’s 6.3 billion euro credit-facility, Italy’s trade-credit insurer Sace SpA will guarantee most of the loan, the people said, asking not to be identified because the application isn’t public. Representatives for Genoa and Sace declined to comment.

There are plans to replace Milan’s San Siro stadium, one of the country’s most iconic, in about three years. AC Milan and Inter Milan soccer teams are in advanced talks with local municipality on the project that will require investments and a project financing of about 1.2 billion euros shared between two teams, according to a statement. The architectural projects are under review include the “Cathedral” by design firm Populous and “The Rings of Milan” by Sportium.

But Serie A still has potential. Juventus’s Cristiano Ronaldo is a celebrity. The Turin team’s player is the most followed person on Facebook, with more than 122 million followers, and has about 228 million Instagram fans, according to the social media platforms. Clubs like AC Milan, Inter Milan and Napoli are still powerful names in European soccer, and in recent years they have been joined by Bergamo-based Atalanta, which is in the European Champions League quarter-final this season.

Italy has major players ready to buy into the leagues’ broadcasting rights revenues, and we think that bodes very well for the long-term potential for Italy.

Joe Dagrosa, a US investor who used to own French soccer team Girondins de Bordeaux

Andrea Sartori, KPMG’s global head of sports, said the Italian league has the most upside potential of all the big leagues in Europe. “As far as the clubs are concerned a few clubs have liquidity issues, so it is easy to see why selling a stake in the league might make sense for them,” he said.

For the first time, no Italian teams made it to the top 10 in KPMG’s ranking of European soccer clubs by valuation. Juventus came in at 11, followed by Inter Milan at 14, but both were overshadowed by six of England’s Premier League teams.

READ MORE: Don't expect great football, Juventus coach tells Serie A fans

“As an investor you need to look to the future, not the past, and the future for Serie A looks positive,” said Joe Dagrosa, a US investor who used to own French soccer team Girondins de Bordeaux and is looking for an investment in a Premier League club. “Italy has major players ready to buy into the leagues’ broadcasting rights revenues, and we think that bodes very well for the long-term potential for Italy.”

Private equity is no stranger to sports investments. CVC had a controlling stake in the Formula One auto racing competition for a decade until 2016, and it’s also bought into English rugby. Elliott Management Corp., the American activist investment firm, owns AC Milan.

Others are skeptical a deal with private equity is the panacea that Italian soccer really needs.

“I’m just wondering whether leagues will regret selling minority stakes now,” says Yannick Ramcke, a sports commentator at the Offthefieldbusiness.de blog. “If the situation gets worse, minority holding PEs could have a path to gaining a majority - which would make sense since I don’t see much upside for PEs at the moment.”