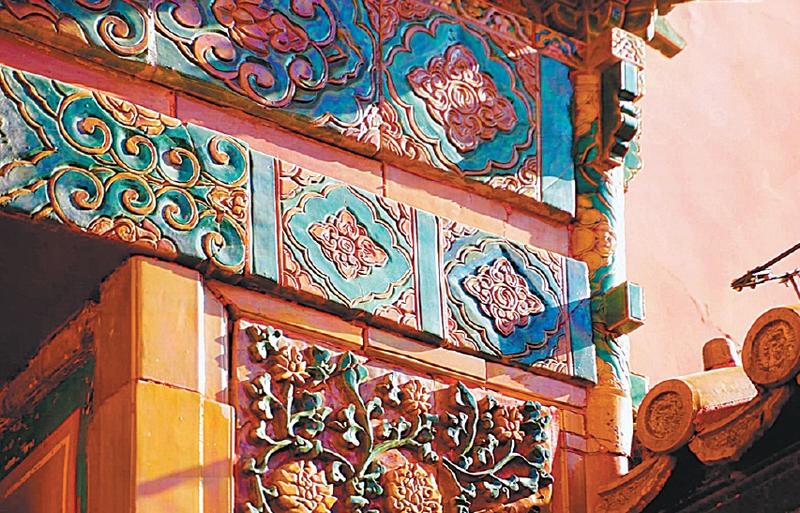

Glazed decorations in the Forbidden City reflect the intricate beauty of ancient Chinese architecture. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Glazed decorations in the Forbidden City reflect the intricate beauty of ancient Chinese architecture. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

What are the colors of the Forbidden City in Beijing? Red and yellow? Yes, but not completely, if you are observant enough.

Thanks to the glaze, called liuli in Chinese, which decorates the doors, roofs and walls, more colors are visible in the Forbidden City, China's former imperial palace, also known as the Palace Museum.

After three years of research on glazed decorations in the compound, an exhibition was launched "on cloud" on Saturday, the country's Cultural and Natural Heritage Day, through the museum's official website to display the colors of imperial architecture.

The research has been jointly done by the museum and Southeast University in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, to unveil the artistic, historical and architectural values of the glaze. A detailed analysis of its materials has been included in the program to reconstruct its production process.

The exhibition, Colored Glaze of the Imperial Palace, uses plain words to explain achievements in the research project to the public through video clips, graphics and 3D modeling.

"Glaze is the best reflection of colors in Chinese architecture and is an indicator of the high status of a construction," says Zhang Tong, a curator of the exhibition who is a professor at Southeast University. "It shows wisdom mixing handicraft and art."

Glaze is a type of ceramic that is produced via certain formula and gets burned in kilns to create an appearance resembling glass.

At the Forbidden City, the glaze work is mainly in green, yellow, blue and black, but white can also be seen. Other than roof decorations, gates are the main location that have used glaze.

In the compound, there are 134 gates decorated with glaze, according to Zhang. They are all digitally showcased in the online exhibition.

"The Forbidden City marks an apex of glaze in China after thousands of years of development," says Wang Jianguo, an academician at the Chinese Academy of Engineering who was leading the research program.

"Glaze represents a grand and splendid aura in Chinese art. It was worshipped in ancient China as a symbol of nobility, like jade."

According to Wang, the earliest glaze found in China dates to the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC), which was unearthed in 1975 from a noble's tomb.

Ancient documents show it was first used in architecture during the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-581), also proved by archaeological discoveries of glaze tiles from the ruins of a capital city from that period.

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), constructional components made of glaze became popular, and glaze bricks and walls appeared.

"People used glaze to mimic wooden structure," Wang says. "It expanded to more occasions, from palaces and nobles' dwellings to temples and public buildings in the countryside during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368)."

That practice remained at the Forbidden City as the glazed gates were designed to imitate patterns of wooden works.

Images on wooden beams can be added by paint, but to create similar patterns, different effects of glaze can only be realized through raw materials and very high temperatures. Today's researchers can analyze which specific chemical composition creates glaze pieces in certain colors, but the ancient artisans only relied on experience. Sometimes, they even had to taste the raw material to make the right choice.

Wang says one reason that makes the Forbidden City glaze exceptional is that it was exclusively used for imperial construction by a rigid ritual system during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

"More architectural forms in glaze appeared, marking the craftsmanship's peak," he says.

The world's earliest known example using glaze in architecture is not in China.

Zhu Meng, a researcher at the Palace Museum, says glaze was used to decorate the Ishtar Gate in the city of Babylon in the sixth century BC.

"However, glaze in Chinese architecture is not purely for decoration," Zhu says. "Glaze is used as tiles in the Forbidden City also because it is a waterproof material."

She adds that glaze of different colors are given certain cultural meanings in China. For example, on Pavilion of Literary Profundity, or Wenyuan Ge, the imperial library within the Forbidden City, black glaze has been used on the roof.

"That is because black represents water, and that expresses good wishes to keep the books away from fire," she says.