(SHI YU / CHINA DAILY)

(SHI YU / CHINA DAILY)

The idea that Beijing and Moscow wanted the United States to remain bogged down in Afghanistan indefinitely so that China and Russia could pursue their policies while the US was engaged there may have some traction in the US, but the reality is different. The US presence in Afghanistan, while it lasted, did not materially impact on Washington's ability to put pressure on the two countries which it regards as its major adversaries. However, the decision recently announced by US President Joe Biden to stop the US experiments with nation-building in various parts of the world and focus instead on proactively defending the liberal and democratic foundations of the Western system, including within the United States itself, and of Western positions in the world represents a major change in US global strategy.

Clearly this change amounts to Washington's recognition that US global power and influence have declined to some degree. Yet the United States remains a superpower with immense resources. That these resources will now be used to strengthen the US home base will potentially make the US even stronger. In foreign policy, Biden's preference for nonmilitary means is designed to play to the strengths of the US-in finance, technology, information, and, not least, global alliances.

Above all, the new doctrine means that Biden seeks to reconsolidate the US' overseas alliances that were strained during the tumultuous four years of Donald Trump's presidency. Not that NATO, or the US-Japan Security Treaty, or any other bilateral security agreement between Washington and its allies and partners was ever in danger of unraveling, or even developing significant cracks. The allies, however, had been losing confidence in the steadiness of Washington's policies which appeared to them to discount allies. Now confidence is being restored, and the US is giving its allies the reassurance they wanted. What is more, they are being invited by Biden to buy more fully into the US' unified strategic vision of the world. Those countries who used to be concerned primarily about Russia, as in NATO, are now asked to expand their threat perception to include China; and vice versa: those in Asia who were historically preoccupied with China are expected to push back against Russia as well.

While the promotion of US-style democracy has been put on the back burner, geopolitical expansion of US alliances and partnerships has not stopped. In Asia, Joe Biden has prioritized strengthening relations with India, both bilaterally and via the Quad format. Vietnam is another country which is actively being cultivated by the Biden administration. Existing alliances are being consolidated, and commitments under them expanded. In Europe, the Biden administration has worked hard to repair the strained relations with Germany, The US' key ally within NATO and the European Union. The "Five Eyes" intelligence-sharing arrangement, which currently includes the US, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, may be expanded with the inclusion of Germany, India and the Republic of Korea.

The failure of nation building in Afghanistan has not led to the withdrawal of ideological tools from Washington's foreign policy toolbox. Just the opposite: they are being sharpened and modernized. The US cannot and will not become a "normal" great power wedded solely to the ways and means of realpolitik. To give ideological underpinning to its competition with China and confrontation with Russia, Washington styles them in terms of "democracy" versus "authoritarianism" rather than cases of major power rivalry which they basically are. Next December, Joe Biden is convening a "summit of democracies" which should provide more inspiration to its allies and partners and orient them to opposing China and Russia on ideological grounds.

Ideological pressure in the form of defense or promotion of human rights, minority rights, and the like will also be applied more actively against those countries the US regards as adversaries. There is essentially nothing new there after the adoption of human rights as an instrument of Washington's foreign policy under President Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s, but many in Washington felt that that instrument was grossly neglected by the Trump administration. Long gone, of course, are expectations in Washington of Russia embracing the Western model of democracy or of China's economic growth leading to social transformation and ultimately to political consequences. Thus, the idea is not to help Russian and Chinese societies embrace liberal democracy; rather, it is to annoy the two countries' political leaderships and hopefully put them off balance at some crucial moment.

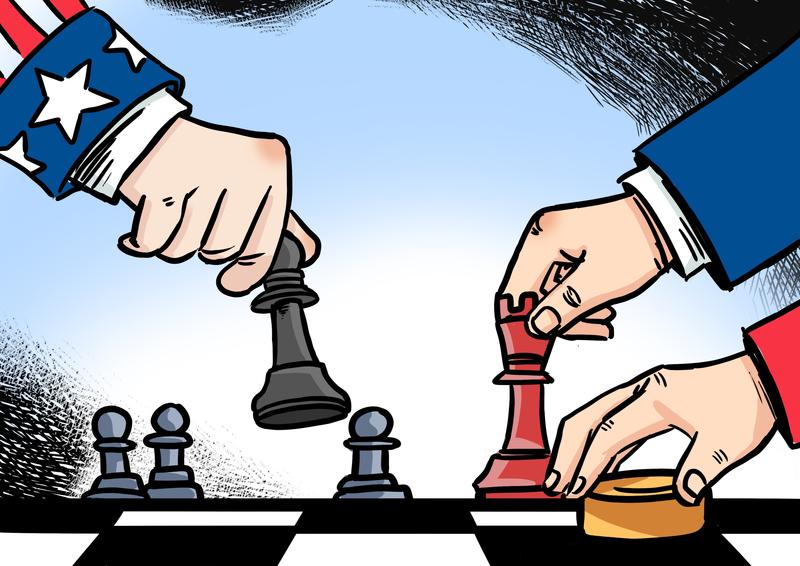

Finally, some people in the US policy establishment continue to toy with the idea of repeating Henry Kissinger's famous feat of using one of the two major US adversaries against the other. This time it will have to be Moscow aligning with Washington against Beijing. But the notion is easy to shoot down. Moscow and Beijing are now close partners, rather than adversaries; Russia doesn't trust the United States; and ruining the friendly relationship between Russia and China for whatever reason would be supreme strategic folly for either country. That this option is nonetheless occasionally mentioned in the US may point to the uncertainty in Washington about other strategies for regaining the US' global dominance.

The author is director of the Carnegie Moscow Center.

The views don't necessarily represent those of China Daily.