Half of Hong Kong lives in public housing. The waiting time for applicants is almost six years. Experts believe there is ample unused land in the New Territories to match the 1,700-hectare Lantau program of 30 years at HK$642 billion. How to unlock that? Wang Yuke reports from Hong Kong.

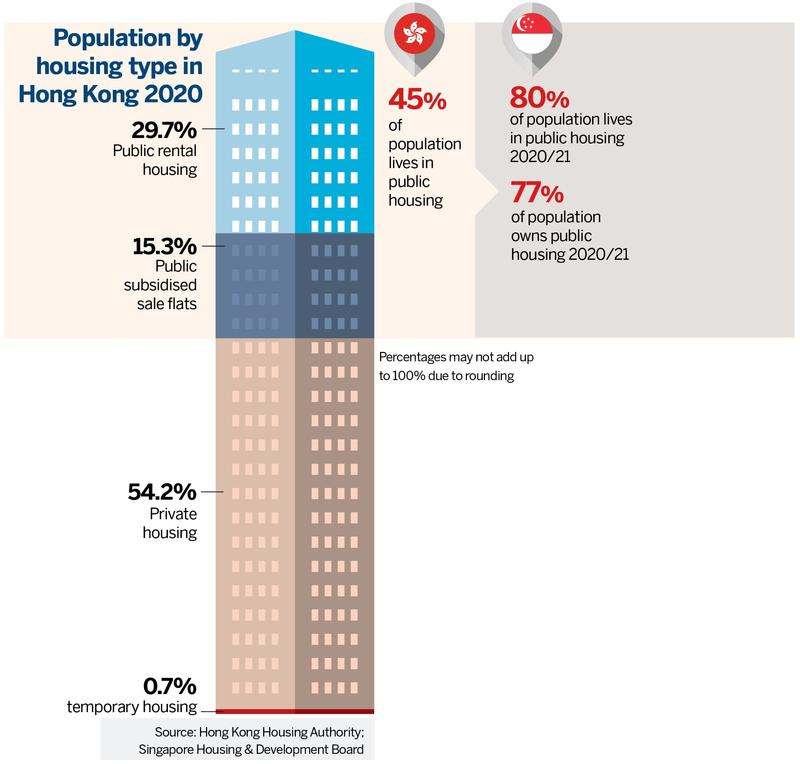

The Hong Kong government owns all its 1,111 square kilometers of land. It sells leases set to expire by 2047. More than half of its population of 7.5 million resides in 78 sq km of the New Territories (excluding the New Territories' rural ancestral lands, which accommodate 7 percent of Hong Kong households). The balance resides in 42 sq km from Boundary Street of Kowloon to Hong Kong Island. The population density is higher than that of Tokyo and London.

Extreme inequality

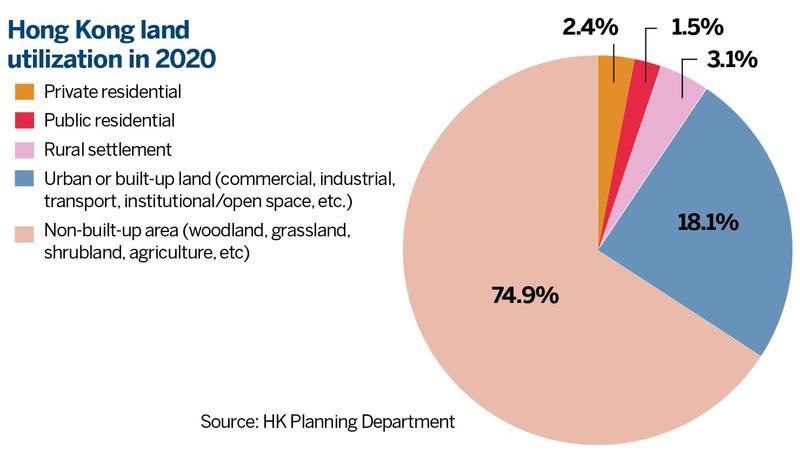

The half that owns property is especially lucky. Hong Kong is one of the most unequal societies in the world, with the richest 10 percent of households earning 44 times that of the poorest, a fact confirmed by a government report in 2017. Most of the territory is wooded parkland, shrubland and wetlands watched hawkishly by activist citizens, environmentalists, and other non-governmental organizations. Scarcity of land exacerbates the housing shortage and widening income gap.

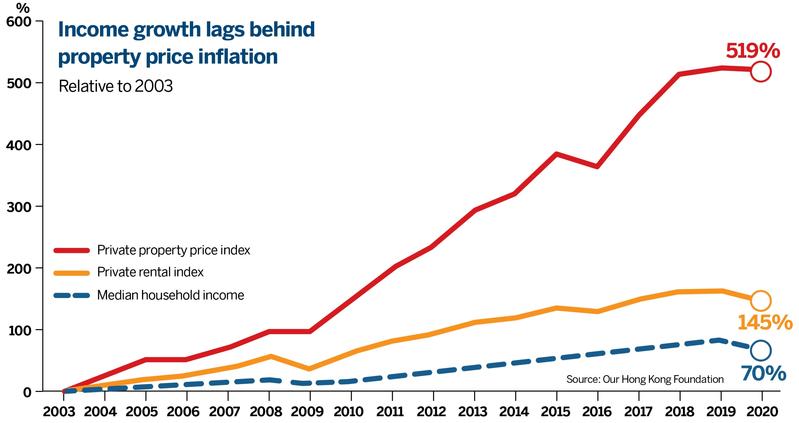

Property values have soared 262 percent (162 percent after adjusted for inflation) over the last 12 years. The ultraconservative banking regime imposes a term limit on the age of the borrower and a loan threshold on the age of the property. Younger borrowers get longer repayment terms, and new properties get higher loans.

Housing reflects and exemplifies the wealth inequity, said Lau Chun-kong, managing director of Valuation & Advisory Services at Colliers. “With better income and job security, elites as well as officials at the top social hierarchy are in a better position to own a house and take out a mortgage than average Hong Kong residents.” The rest line up for subsidized public housing. The public rental housing (PRH) program is oversubscribed and undersupplied.

Long waiting line for a roof

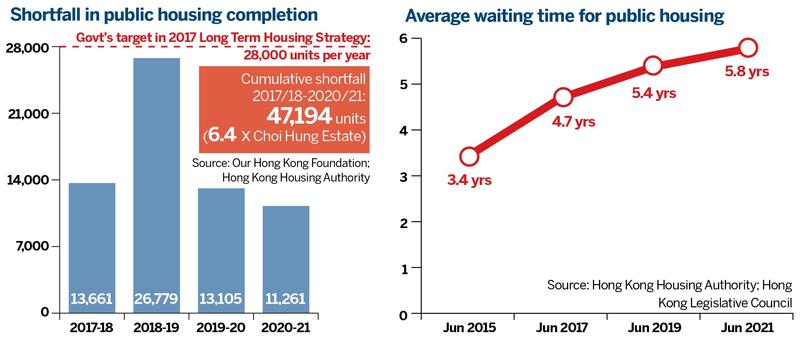

The waiting time for applicants is almost six years. More than 153,900 general applications and over 100,800 non-elderly one-person applications are awaiting action. This wait is the longest in more than 20 years. It was 1.8 years in 2009. The stated Housing Authority (HA) target of three years for new applicants seems unrealistic. The HA pledged to supply 75,000 units from 2011 to 2016. It managed 62,559, a 17 percent shortfall.

The 2016 Policy Address flagged 210,000 units in five years, of which 70 percent — 147,000 — would be public housing. Actual production was 79,099, meeting only 53 percent of the target. Ryan Yip, head of Land & Housing Research at think tank Our Hong Kong Foundation, calculated the deficit of 20,500 units under the 2017 Long Term Housing Strategy for 180,000 units — as equivalent to 1.6 times the area of Taikoo Shing. Yip is pessimistic about the production goal of 15,000 new units a year from 2021 through 2025.

The PRH financing is unsustainable, adds Jacqueline Hui, a researcher at Our Hong Kong Foundation. The HA is meant to use the rental income to cover the construction and maintenance of public housing units. However, the authority is negatively impacted by rising construction and maintenance costs. Under the current arrangements, it is projected to accumulate an operating deficit of HK$490 billion ($62.9 billion) by 2041-42, according to Hui’s research.

The average monthly rent in the city is HK$20,858, exceeding the median monthly income of HK$18,400. That forces the housing underclass to survive in subdivided flats averaging 132 square feet. The average living space for public rental housing tenants in 2014 to 2020 ranged from 13 to 13.5 square meters per person, while subdivided cells allowed 4.9 sq m per capita, according to a 2019 government survey. Singapore, densely populated with an even smaller land area, provides 30 sq m per person for 81 percent of its residents in public housing.

Land premium struggle

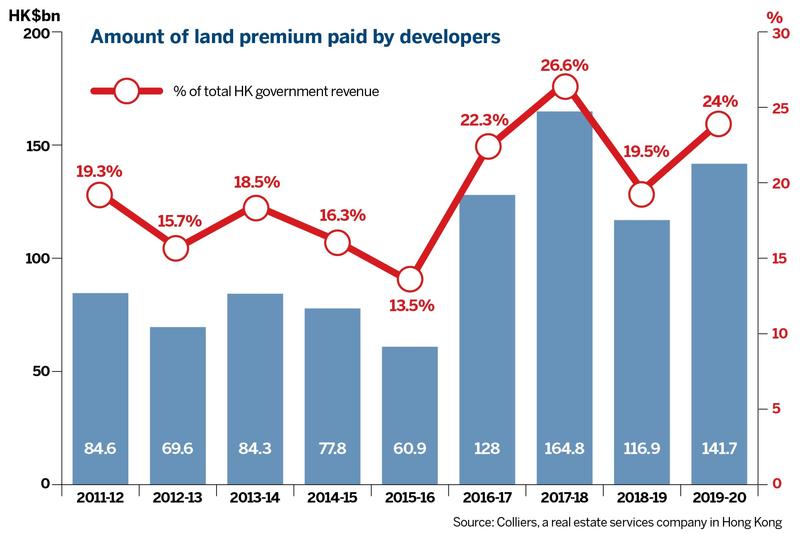

The government derives a fifth of its annual revenues from land premiums to convert agricultural land to residential or commercial use. The “agricultural” classification is simply a restriction on building; it does not imply farming activity. The negotiations on lease modification are complex, time-consuming, and can take years, even half a decade, for approval.

The premium is levied on the projected increase in land value after lease modification. Depending on the property cycle, the developer may choose not to commit construction. Lau calls attention to the 100 million sq ft (929 hectares) in the New Territories locked up between four major developers: Henderson (over 40 million), Sun Hung Kai (over 20 million), New World (over 20 million) and Cheung Kong (10 million).

About 2,400 hectares of ancestral or Tso/Tong land comprise fragmented plots with irregular borders as “land assembly” is not completed, Lau said. “That’s why the government is stepping up land assembly for more complete and sizeable land redevelopment. Without consolidation, they can only build very low-density residences. The land isn’t best utilized,” he added.

Pushback from special interest groups further delays the housing development process. Groups and individuals can lodge objections to the Town Planning Board. Residents may not want a particular facility relocated near them, or green groups may object to removal of a green belt. The consultation procedure is inefficient and duplicated, says Lau. “Everyone comes into the hearing session voicing their opinions, but many objections pertain to the same issue.”

Qiao Shitong, a professor of law at Duke Law School, who specializes in property law, said that developers would acquire expensive new leases when “the cost of developing the existing leased land through lease modification can be more expensive than purchasing new land leases from the government.”

Idle land banks

To prohibit intentional hoarding of land without construction, the government has stepped up efforts by imposing a building covenant, which requires the owner of a lot to complete residential property construction within a specific period, generally four to six years, after the lease modification is executed. The covenant does have teeth, as the penalty for failing to fulfill the agreement involves over HK$100 million in fines.

Nevertheless, the deterrent alone is not enough. The lease modification negotiations face a formidable bureaucracy. Transport, railways, environmental protection, planning, fire safety, and other government departments impose conditions, amendments and objections, plus hold veto power on specific proposals. About 1,012 hectares meant for housing are currently held idle by the property cartel, according to government estimates.

Qiao deems Hong Kong’s housing shortage to be a paradox of lack of housing in an abundance of buildable land. Only 25 percent of the total land area is builtup, while the remaining 75 percent is woodland, shrubland, grassland, or wetland and country parks, of which only 3.9 percent is devoted to nonrural residential uses.

Ample housing capacity

Qiao suggests local residents be given “land options for housing” (LOHs). LOH holders rather than the government would sell these to developers and indigenous villagers. “Those buyers would compete with each other to purchase to build high-density housing, giving the LOH holders a stake to move land from low-value to high-value uses while providing ample compensation to existing stakeholders.

“The Hong Kong government, developers, and indigenous villagers control most of the developable land in Hong Kong, which includes 391 hectares of unleased residential land, 3,380 hectares of village-type development land, 4,400 hectares of agricultural land, of which only 700 hectares are actively farmed, and 1,600 hectares of brownfields,” Qiao said. There is an absence of focused measures to deal with existing land occupiers or users, he added.

That is precisely the point Augustine Ng, a retired 30-year career town planner and former member of the Central Policy Unit, made in his detailed 8,000-word counterproposal of October 2018 to the “Lantau Tomorrow Vision”, the government plan to create 1,700 hectares of artificial islands off Lantau Island to hold 400,000 units that would be built over 20 to 30 years for 1.1 million residents, at a cost of HK$642 billion. Critics worry that the project would wipe out half the territory’s foreign reserves and take three decades.

Ng proposed a radical reversal of the “hope value”, or the expectation developers that their land will appreciate over time. The government could declare that it will not renew the New Territories leases with the developers for the unbuilt land after June 30, 2047, and that the government would retain the land with a minimum buyback offer. Such a move would flush out all the parcels at one go, as all the developers rush to cash in, Ng said. Overnight, the government would get more than the 1,700 hectares it is planning from the Lantau development, and at a far lower cost, he added.

Owning a house in Hong Kong could be an unattainable dream even to a middle-class household, let alone to a household scraping by on minimum wages. In response to the dire need of residents, the government introduced the Home Ownership Scheme and Tenant Purchase Scheme in an effort to allow better-off tenants of public rental flats to buy housing at an affordable price and vacate rental flats for more-needy residents. Despite its ability to boost home affordability, it’s still a contentious strategy. A problem with the HOS and TPS is, if the buyer wants to sell the property in the private market after a few years, they have to repay the unpaid land premium, which, instead of being fixed at time of purchase, changes with market prices. Consequently, only a fraction of tenants can afford the formidably high premium, said Hui from Our Hong Kong Foundation.

Infrastructure investment

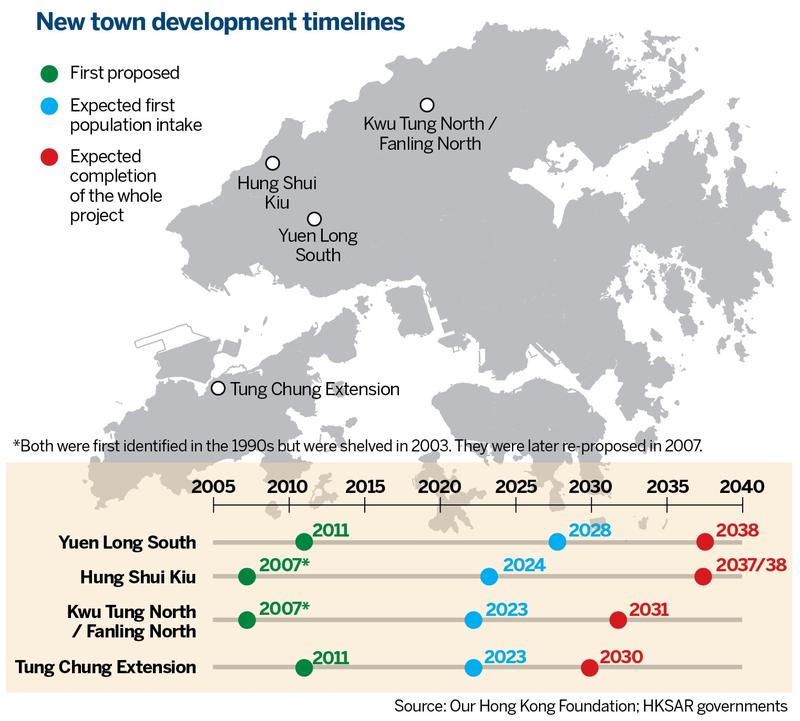

A supporting infrastructure of roads, rail, public transport, sewage system, retail shops, electricity and piped water is vital for housing location. The SAR government has followed a demand-led response to infrastructure. This is self-defeating, said Ryan Ip of Our Hong Kong Foundation. He points to the proactive infrastructure provision of the Singapore and Chinese-mainland authorities.

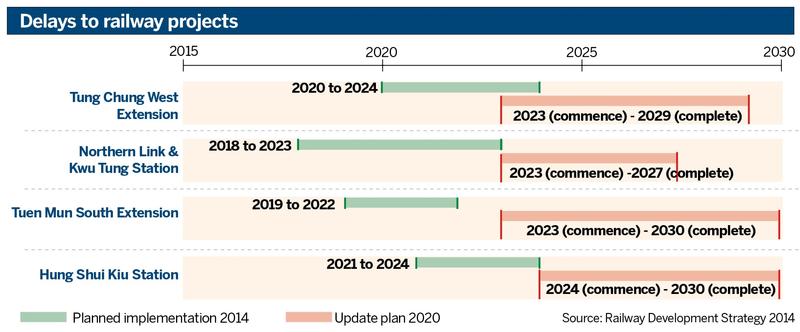

The 2014 Railway Development Strategy identified seven projects to be completed by 2031. Construction has not begun. The deadline will not be met. Developers will have no reason to commit to housing construction. Ip expects this lack of railway completion to inhibit housing supply over the next decade.

The North Metropolis initiative that covers Shenzhen-Hong Kong Boundary Control Points Economic Belt, Yuen Long, and North District, could offer relief to the housing situation in Hong Kong. “The proposed five MTR train lines with 10 stations will prompt new high-density developments on top of the adjoining stations,” Lau of Colliers said. “It’s high time the government executes what it promised.”

What to do next?

Streamline procedures for land modifications and town planning approvals

Review the distribution of land for housing and other purposes (brownfields, woodland, grassland, etc.)

Step up infrastructure ahead of potential housing development

Consider “land options for housing” to make residents stakeholders

Speed up new town development and railway projects

Incentivize developers to release their New Territories land banks

Contact the writer at jenny@chinadailyhk.com