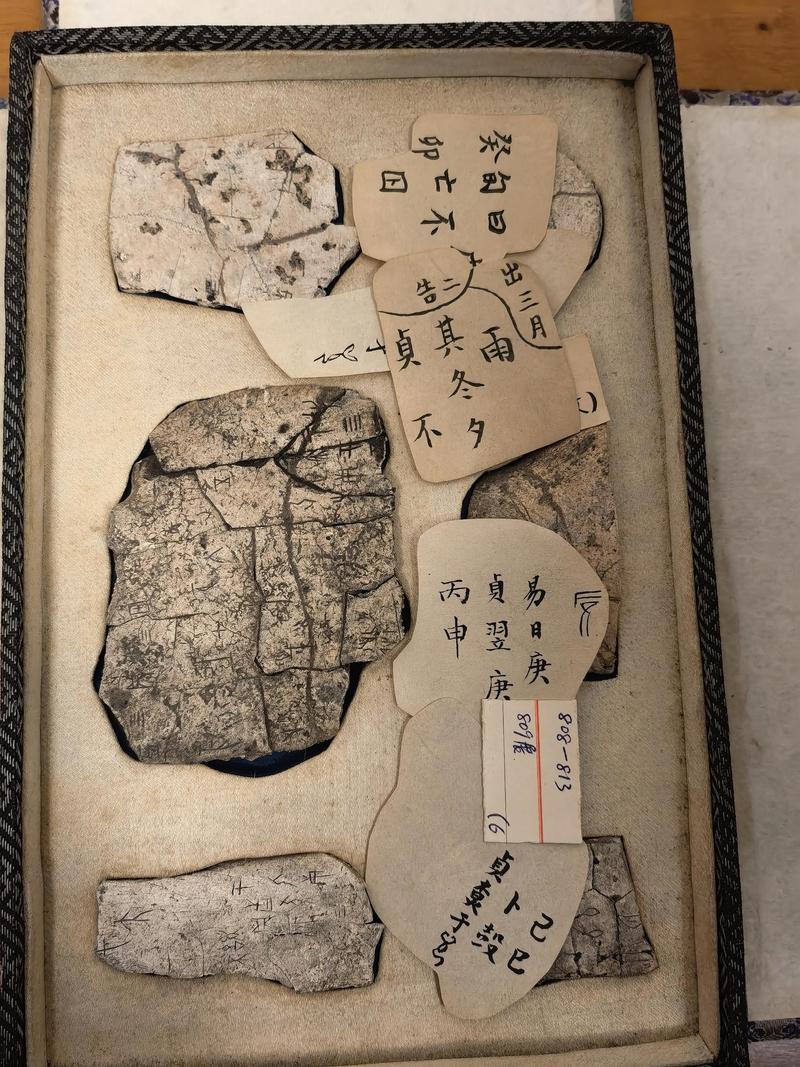

Oracle bones housed in Nanjing University, Jiangsu province, that were donated by US Sinologist John Calvin Ferguson. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Oracle bones housed in Nanjing University, Jiangsu province, that were donated by US Sinologist John Calvin Ferguson. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

More than one century after being unearthed, hundreds of pieces of oracle bones that have been kept in the warehouse of a top university in Jiangsu province now have the chance to be decoded, thanks to a new academic project.

Nanjing University in the provincial capital announced in early November the launch of a comprehensive study and categorization of the bones that date to the late Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC). Systematic recordings of these pieces through traditional ink rubbings and digitized approaches will also begin.

About 600 pieces of oracle bones are now housed at Nanjing University Museum, making it the third-largest collection of its kind among Chinese colleges after Peking University and Tsinghua University, both in Beijing.

According to Shi Mei, director of the museum and host of the academic program, the about 3,300-year-old bones were owned by some well-known collectors around 1900. They include Liu E, a famed novelist of the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911); Wang Yirong, who is believed to have been the first person to notice oracle bones among materials for traditional Chinese medicine in 1899; and Xu Fang (1864-1916), a teacher of the last emperor, Puyi.

Some of the bones were donated by John Calvin Ferguson, an American Sinologist who was president of the University of Nanking, a predecessor of Nanjing University that was formed in 1952.

"However, due to the lack of enough talented scholars, detailed studies on the bones hadn't started for a long time," Shi says.

Oracle bone inscriptions compose the oldest-known Chinese writing system. The findings, mostly from the Yinxu site in Anyang, Henan province, not only prove that Shang Dynasty history is more than myth, but also indicate the beginning of an uninterrupted lineage of Chinese language, as present-day written characters can trace their history to the inscriptions.

In spite of the high status of oracle bones, difficulty in relevant studies meant expertise to decode the obscure writings was in high demand.

Scattered fragments of oracle bones first began to emerge around Anyang in the late 1890s. In 1924, the University of Nanking became the first Chinese university to include a course on oracle bone inscriptions in its syllabus. Four years later, the first linguistics treatise on the inscriptions was also published in Nanjing.

Nonetheless, since the first official archaeological project began at the Yinxu site in 1928, the oracle bones that were excavated became a focal item in the field.

"In China, the spotlight of such studies is mainly on oracle bone collections in public institutions, like the National Library of China and the Palace Museum in Beijing," Shi says.

"There's a big potential to know more about collections in colleges that may yield surprises," she adds.

In 2008, Peking University published complete information on its oracle bone collection, followed by Fudan University in Shanghai in 2019, and Jilin University last year. Other than that, most universities still have a vague understanding of their own inventory. In recent years, Shi has found the opportunity to restart oracle bone-related work at her university after decades of hiatus.

In 2020, a research center focusing on excavated ancient documentation was established at the School of Liberal Arts, Nanjing University, and the oracle bones in the museum there offered firsthand material for relevant research.

Cheng Shaoxuan, a professor and head of the research center, says the upcoming program will cover various fields of oracle bone studies to dig deeper into relevant records and files, and nurture talent on paleography at the university.

As he points out, "rejoining" of scattered oracle bone fragments, which may exist in different places, is also a focal work. Academic exchanges among various institutions are crucial to put the broken puzzles of history back together.

Compared with scholars from a century ago, modern scholars are luckier to be supported by new technologies. According to Shi, her museum will cooperate with the university's School of Artificial Intelligence to look for the possibility of using the technology to facilitate the rejoining work based on analysis of big data.

She says cooperation with other branches of natural sciences will also breed new achievement. For example, modern material sciences can help to better conserve the fragile bones.

Xu, the above-mentioned old-time collector, once delicately designed book-shaped caskets for the oracle bones. They have been on the university museum's bookshelf for a long time. Perhaps, the archaic words will finally be "read", thanks to such modern support.