Understanding the deep cultural connotations of traditional designs is its own path to enlightenment, Xu Lin reports.

Editor's note: There are 43 items inscribed on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage lists that not only bear witness to the past glories of Chinese civilization, but also continue to shine today. China Daily looks at the protection and inheritance of some of these cultural legacies. In this installment, we talk to scholars and inheritors at the cutting edge of Chinese paper craft.

A pair of scissors and a piece of paper — that's all 55-year-old Liu Jieqiong needs to create delicate works of art. What's more impressive is that it's done off the top of her head without the aid of, or need to refer to, a drawn pattern.

The themes vary between regions. While many paper-cuts in northern China are about figures and folk stories, there are more flowers and birds in the paper-cuts of southern China.

Li Zhengming, painter and paper-cutting artist

This is the unrivaled skill of paper-cutting, an art form found all over China, from the unrestrained and abstract varieties in the north to the intricate and vivid pieces in the south.

Like Liu, craftspeople with dexterous hands cut and carve various patterns and images with scissors and burins, such as birds, animals, flowers and fruits, as well as mythological and historical figures, each with their own cultural connotations.

The art form takes inspiration from the daily lives of Chinese people, who have long used paper-cuts as a facet of different folk activities and to decorate their homes.

The earliest known unearthed paper-cuts in China — featuring horses, monkeys, flowers and geometric figures — were found in Turpan, in today's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, during the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-581).

In 2009, Chinese paper-cutting was inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

"The patterns are all in my heart. You can understand life through paper-cutting. Life is the script of art, and art is reflective of life," says Liu, from Yanchuan county, Shaanxi province.

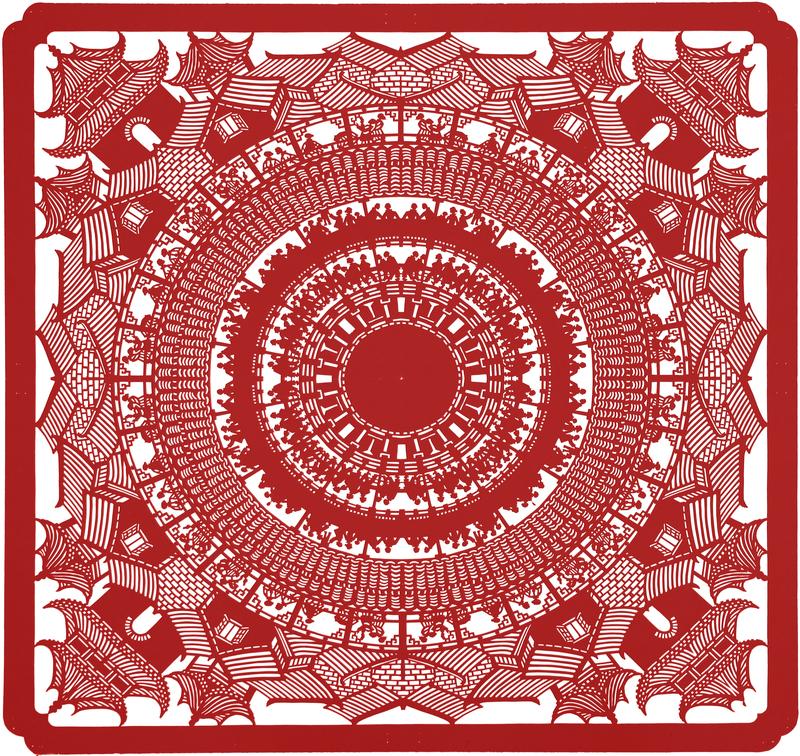

Paper-cut artwork created by Beijing-based painter Li Zhengming. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Paper-cut artwork created by Beijing-based painter Li Zhengming. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Under the guidance of her mother Gao Fenglian, a national intangible cultural heritage inheritor of the craft, she gradually mastered the technique and understood the cultural meaning behind the paper-cuts.

"My mother rarely shared her perception of paper-cutting. She just said that only when I grasp the subtlety on my own, can I understand its deep culture and philosophy," Liu says.

"When you have a thorough understanding of the formulas and the patterns, you will know the essence of life and how you should live it."

Through ups and downs, it took a long time for Liu to understand that with such a traditional folk culture, "you have to find your own path to enlightenment". It's not something that can be taught. She's now familiar with the folk customs behind the local paper-cutting patterns.

She says it's mainly about the totem worship of animals and plants, representing people's pursuit of a better life.

Different pattern combinations have various auspicious meanings, such as the continuance of a family line, a bumper grain harvest or prosperous life. For example, the classic pattern of a rabbit with a snake wound around it is an indicator of a rich and happy life, and is often used to decorate the bridal chamber at a wedding.

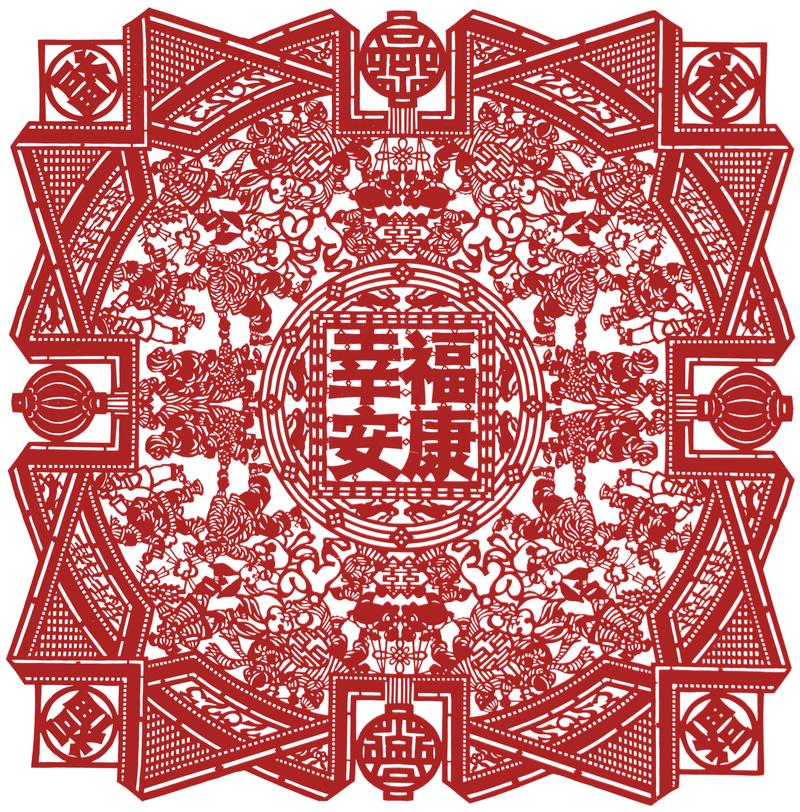

Paper-cut artwork created by Beijing-based painter Li Zhengming. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Paper-cut artwork created by Beijing-based painter Li Zhengming. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In many regions, the traditional skill is often handed down from generation to generation of women within the family. Liu's mother gave her an old pair of scissors that was once used by Liu's great-grandmother.

In China, different paper-cuts are used for weddings, funerals and births, as well as specific designs for old age and sickness. They're also used to invoke spirits for the frightened and the sick — even those of the dead — and to pray for good weather.

Liu says that, in the past, when a child was sick, the mother would make a paper-cut of dolls holding hands to act as a substitute to lure the "bad spirits" away from the child.

She explains that in northern Shaanxi, while the man's most important tool is a hoe for plowing the fields to feed the family, the woman's is her scissors, used to make clothes and keep the family warm. They are cultural symbols and ensure an agricultural society's ideal of peace and order.

She recalls that, during her childhood, at Spring Festival, children would go to see the paper-cuts decorating the traditional cave dwellings, and they all believed that the most beautiful ones were made by their own mother. There are rules about which patterns should be displayed as window decorations on different days of the festival.

Liu attributes the different types of paper-cuts to the indigenous cultures and topography of the country.

Liu Jieqiong is a master of paper-cutting from Yanchuan county, Shaanxi province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Liu Jieqiong is a master of paper-cutting from Yanchuan county, Shaanxi province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Painter and paper-cutting artist Li Zhengming, 70, agrees.

"The themes vary between regions. While many paper-cuts in northern China are about figures and folk stories, there are more flowers and birds in the paper-cuts of southern China," says Li, from Beijing, who started to collect paper-cuts from all over China in 1976, before taking up the art form himself when he retired in 2014.

"In all art forms, including paper-cutting, it's essential to have continuous innovation, which originates from life. You should not be restricted within the framework of traditional themes," he says.

His paper-cuts are mainly about different aspects of social life, based on his careful observations.

He uses painting to design paper-cuts, and it takes at least a week to finish a piece. He combines traditional folk images with other Chinese cultural symbols, such as seal script and oracle bone inscriptions, in his paper-cut designs.

Every Spring Festival, he makes a paper-cut on the theme of whichever of the 12 Chinese zodiac animals the new year ushers forth. He also creates paper-cuts to record festive scenes, such as family reunions and temple fairs.

He creates a design at first and uses a burin to carefully carve out the complicated patterns. He often folds the 76-centimeter square paper several times, to ensure a symmetrical design which adheres to traditional Chinese aesthetics. Finally, he puts in some different elements to add a little contrast to the symmetry.

Tai Gaodi, associate researcher at Chinese National Academy of Arts, says: "Chinese paper-cutting is closely related to the nation's original culture and religious beliefs, such as reproductive worship, praying for blessings and warding off disasters. It contains deep cultural value, as well as traditional Chinese philosophy and morals."

In Chaozhou, Guangdong province, paper-cuts are pasted onto sacrificial offerings at such rituals and local craftspeople also chisel patterns in copper or gold foil. In Yueqing, Zhejiang province, it's a tradition to paste paper-cuts with intricate patterns on large dragon boat-shaped lanterns during Lantern Festival.

Tai adds that the paper-cuts of ethnic groups in China have different characteristics, showcasing their ancestors' stories and mythology, as well as religious and folk traditions.

Liu notes that development is needed for future inheritance. She recently worked on a collaboration to make silver ornaments based on her paper-cut patterns.

Liu, as president of Yanchuan county's Women's Cultural Artists Association, often delivers speeches at colleges to promote the culture of paper-cutting among youngsters.

Tai says: "Like other folk arts, paper-cutting has less practical use than before — there are fewer people using them nowadays. But paper-cutting can be revived in other ways. Its patterns can be used to make creative cultural products and cartoons, for example, or even to be printed on clothes."

Contact the writer at xulin@chinadaily.com.cn